I grew up at a time when Gaddafi and his regime still retained some socialist elements in their policies and rhetoric, but were already starting to break away from traditional socialist ideas.

Libya was one of the few countries in North Africa to maintain close relations with the GDR. Their collaboration involved exchanging goods and technical expertise and offering one another political support. The latter came to an end, however, after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Similarly to the GDR (as I discovered when I arrived here), murals were used as a means of spreading socialist ideas and to support the regime. Those political murals were often part of a broader propaganda campaign.

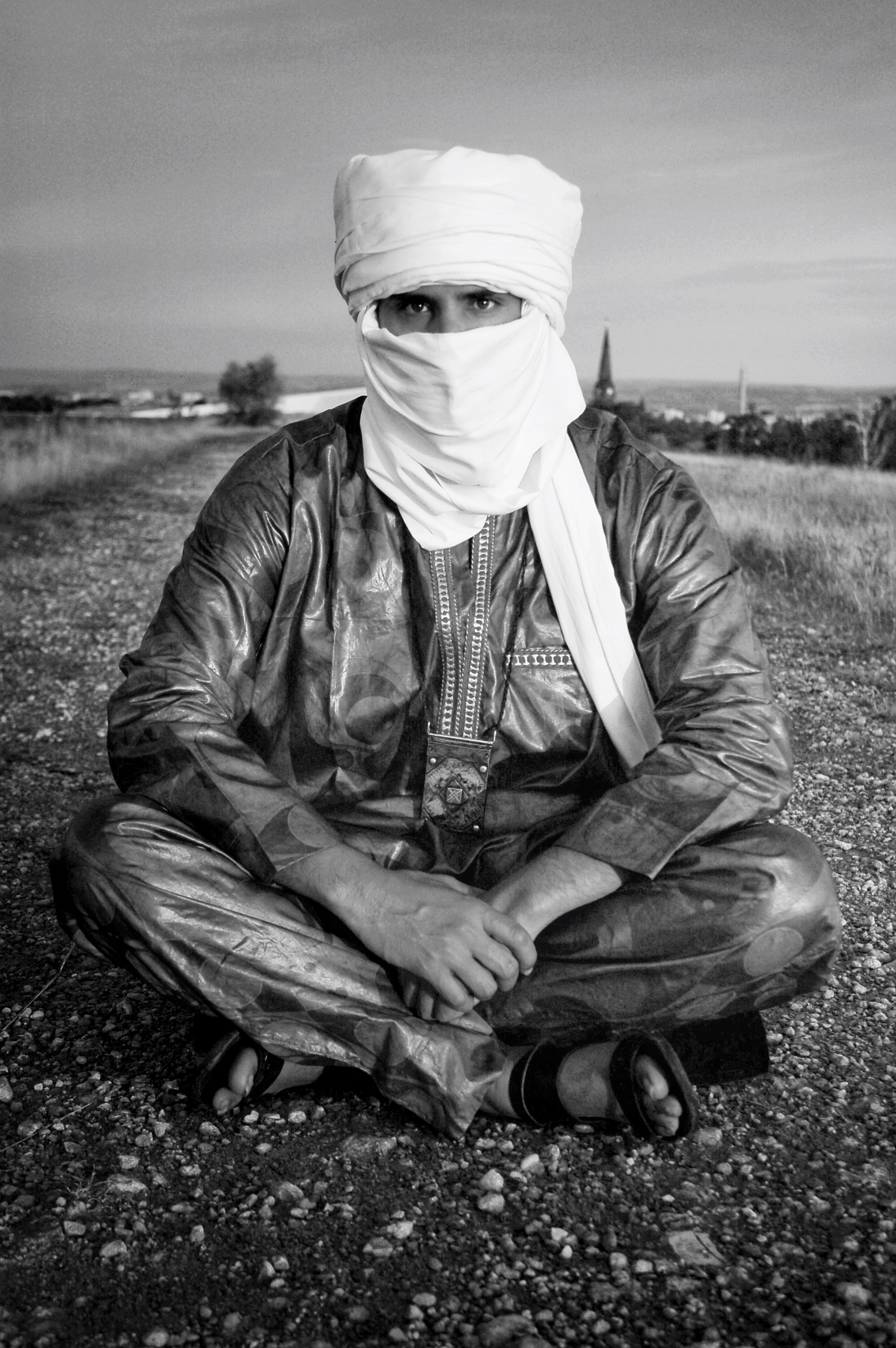

Moussa in Dresden

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

While Lenin appeared as a leader on huge mosaics in East Germany, in our country it was Gaddafi. Public spaces were emblazoned with symbols of socialism, scenes from working class people’s everyday lives and images celebrating how the country had progressed and developed under the socialist regime. The murals were designed to raise viewers’ awareness of political aims and increase their loyalty to the government.

All this did not really exist for me. Because the people in the far south, on the edge of the Sahara, tended to be forgotten. Our political education was nevertheless very similar to that in the GDR. My experience here in the East, in Dresden, discovering relics of the time before reunification, was like travelling back in time to a past that is two thousand kilometres away.

Moussa bei seiner Arbeit in der Kunstgießerei GEBR Ihle Bildguss GmbH

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Before the Libyan civil war in 2011, art that resisted Muammar al-Gaddafi’s regime only took on a limited number of forms. The authoritarian regime repressed all types of oppositional art and culture, and strictly controlled artistic production within the country’s borders. Even so, there were a handful of artists and intellectuals who incorporated subtle signs of resistance into their works by bringing up sensitive topics metaphorically or cryptically. Such forms of resistance were, however, few and far between, and were often produced and spread underground or in other countries.

It was the outbreak of civil war and the overthrowing of the Gaddafi regime that allowed the emergence of resistance art: various forms of artistic expression opposing the authoritarian regime and fighting for freedom and democracy in Libya.

Moussa im Atelier mit seinem Kunstwerk Der Pass / Passport / جواز السفر

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Freedom of expression, public debate involving different political views, a willingness to engage in discourse - it took a while for me to trust this system. I have lived here for almost ten years now, and am still excited about all the possibilities within a democracy. I am not a citizen of this country, but I am a human who lives here and wants to help shape this country. The instrument I use to take part in social discourse is art. A medium which reaches people beyond the spoken word.

I got the chance to run workshops as part of the artistic programme accompanying the “Revolutionary Romances” exhibition. We invited participants to design their own posters using screen printing. In our printing workshop, we wanted to focus in on people’s highly personal views on what our society should be like. Nose to nose – side by side – hand in hand – heart to heart? What kind of a world do we live in? And what kind of a world would you like to live in?

Workshop “Deine Botschaft – Dein Plakat – selber drucken mit Siebdruck” with Moussa Mbarek and Yvonn Spauschus

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photo: Iona Dutz

One aim of particular importance to us was to engage with people from immigrant families. We were interested in the perspective of that section of the population, which is often only portrayed as a homogeneous mass.

Where else can you get first-hand experience of what it is like living in other places or in other societies?

The result was an extremely diverse range of subjects and statements. People got to know one another and struck up conversations. One topic that wove its way through all the workshops was peace. That wish for the future was a recurring motif among participants of every nationality.

Participants from Sudan and South Korea worked together on the issue of women’s rights, people from Syria and Libya tackled the subject of freedom, the impending elections in Europe were also a hot topic.

Workshop “Deine Botschaft – Dein Plakat – selber drucken mit Siebdruck” with Moussa Mbarek and Yvonn Spauschus

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photo: Iona Dutz

It is only when you lose the freedom to air your wishes and thoughts, to think freely and to question social processes, that you know what it is to lose democracy.

Perhaps there would be less war in the world if people were able to think more freely. If religions and political dogmas are left aside, after all, what is left is people; simply people who want to live in peace.

I was one little dot in that homogeneous, grey mass of refugees. I did not have such possibilities in my old country. Museums were not a place to share thoughts. Museums were places with a police patrol in front of them.

Here in Germany, in Dresden, my new homeland, anything is possible. Living in freedom, shaping democratic processes together, arguing over opinions with no fear of repression: those are things that are also made possible by the freedom of art. I think, people who are afraid of art are afraid of themselves.

Moussa at work at the art foundry GEBR Ihle Bildguss GmbH

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Also of Interest

On 13 October 2022, the Albertinum of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden hosted the conference “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-)Communist Europe.” A report by Julia Tatiana Bailey and Christopher Williams-Wynn.

The "ostZONE" series, part of the special exhibition "Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR", created a space within the Albertinum for anyone to share conversations, questions, and memories of life in the GDR and in modern-day eastern Germany. Bela Álvarez organized the "Holding the Strings" ("Die Fäden in der Hand halten") workshop, bringing the power of images as well as the power of our hands into focus.

The "ostZONE" series, part of the special exhibition "Revolutionary Romances? Global Art Histories in the GDR", created a space within the Albertinum for anyone to share conversations, questions, and memories of life in the GDR and in modern-day eastern Germany. Read about Hung The Cao and his workshop with contemporaries "Jeans nach Dienstschluss" ("Jeans after Hours").