Filmstill aus Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper: The Guestbook (2019)

© Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper, VG-Bild-Kunst Bonn 2023

Chih: It makes sense to think about my artistic practices in the context of Taiwan’s historical circumstances. Those two themes, social justice and decolonization, are indeed deeply embedded in Taiwan’s art education system. Therefore, it feels like a natural approach for me to engage in the discourse on decolonization and transjustice through my approach to art. That is also why I am keen to gain a deeper understanding of the European academic perspective, as it appears to differ significantly from my own. As an example, I often mention that in Taiwan, discussions about race are rarely a focal point, whereas in the European context, they are essential. My educational experience in the European academic system has allowed me to critically evaluate my own practice and identify several blind spots in my thinking.

Filmstill aus Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper: The Guestbook (2019)

© Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper, VG-Bild-Kunst Bonn 2023

Gregor: The world seems chaotic, confusing, unequal, full of crises. It is—and has always been—complex. So how can we orientate ourselves; how can we navigate through it? I realized that in order to understand and transform the world in which we live, we have to understand history. To see how everything has evolved step by step, up to the current situation. But that is not as easy as it sounds at the beginning. When you begin, you quickly realise that there is no one, single “history.” History is always plural; many parallel stories that challenge one another. History is never neutral. It is usually interpreted by those in power: they write and rewrite history to serve their interests, they suppress and silence other voices. So you have to make a choice. History is always a construction (but not a random fiction) and you can choose to use it as a tool for emancipation, to engage in the necessary processes of transforming existing postcolonial, neocolonial or colonial capitalist patriarchal structures, or to continue reproducing oppressive and unequal power structures.

Gregor: That’s definitely part of it. History changed just as fast as society did. The past was rewritten from the “winner’s” perspective. Great chunks of embodied memories and life experience were taken away and denied by that new society. Although I was very young, that experience was mediated to me by my family and my social surroundings. It taught me the relativity of history and its connection to a certain present from a specific perspective.

Cinemagraph from Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper: The Guestbook (2019)

© Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper, VG-Bild-Kunst Bonn 2023, Cinemagraph: Jacob Franke

Chih and Gregor: Indeed, the narratives within our works often share correlations and connections. This is not only because they explore common thematic studies but also because we aim to shed light on the complexity of historicity. History is not a singular, linear narrative; rather, it comprises numerous overlooked details that escape the purview of our educational system. This is why our working process is simultaneously a journey of learning and unlearning. For example, it is crucial to examine pre-war Berlin to gain deeper insights into Germany’s colonial circumstances. However, if we also consider that key figures from the early Chinese Communist Party lived in Berlin in that period, it adds another layer to our understanding of China’s foreign aid initiatives and its modern relationship with Africa. This is precisely the approach we employed in constructing the storyline of The Guestbook.

Chih and Gregor: To comprehend the history of a location, be it in Europe or Asia, it is equally important to study the history beyond that specific region. These stories run in parallel and interconnect. Consequently, our research process is time-consuming as we continually build upon our previous work, striving to add more layers of depth. Recently we have been engaged in a new project in Cameroon that explores the transitional justice associated with street names, an outcome linked to Café Togo. Concurrently, we are also working on another project in Togo, delving into the colonial outpost, which ties in with the archival material we used in The Guestbook. We believe that the more our audience engages with our work, the greater their understanding of the broader picture becomes.

Filmstill aus Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper: The Guestbook (2019)

© Musquiqui Chihying/Gregor Kasper, VG-Bild-Kunst Bonn 2023

Chih and Gregor: We do share a profound affinity for storytelling, particularly narratives that offer a lens through which we can reflect upon and re-evaluate our identities, social construction and our position in the ever-flowing currents of history. In our artistic pursuit, we have consciously chosen a format that blends documentary elements with fictional storytelling and performance. That deliberate fusion serves a dual purpose. It enables us not only to vividly address the pressing issues we seek to engage with, but also to envision potential historical trajectories that might plausibly have unfolded. Drawing inspiration from the insightful words of Cameroonian film director Jean-Pierre Bekolo, who eloquently described film-making as a perpetual “what if,” our cinematic endeavors are an exploration of the uncharted territories of “potential history” activism and living experience.

Chih and Gregor: As we mentioned, we’re now finishing a site-specific follow up to Café Togo, Café Cameroon, which we shot during the RAVI biennial in Yaoundé this summer. It places the questions asked in Café Togo in the context of Cameroon. With the Togolese artist Elom 20ce, we also just made the film The Currency—Sensing 1 Agbogbloshie, which premiered recently at the Locarno Film Festival. This work is part of our series The Currency, in which we reflect on currencies and values in the context of global capitalism, technological developments and digitalization, as well as visions of currencies that are not focused on capitalist economic logics. As part of this project, we’re also going to Nigeria in a month to do “The Currency Lab”—a public format involving an exhibition and a workshop series. In Lagos we’ll be working with local e-waste workers to jointly examine our research on the global circulation of electronic devices.

Also of interest:

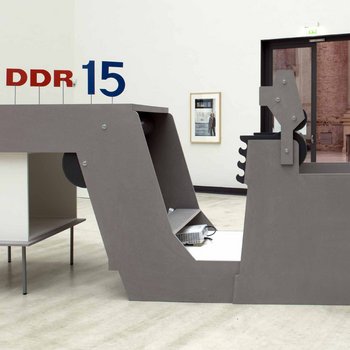

In 2022 and 2023, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden are fixing their gaze once again on GDR times in their research and exhibition project “Kontrapunkte” (“counterpoints”), funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. Based on their own holdings and the history of their collection, fresh perspectives are being developed on art in the GDR, how it was seen and the significance allotted to it in the past and present, with the addition of international viewpoints. To this end, a range of physical and digital formats are in the pipeline, information on which will be provided on this platform.

Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran curated the first of our film series for the Kontrapunkte project, which deals with the cultural interweavings of the GDR and Vietnam. In conversation with Kathleen Reinhardt from the Albertinum, she explains the questions that preoccupied her in the process.

Is it possible to react aesthetically to an event like the wartime invasion of the Wehrmacht? Sergej Paradjanov has tried to do just that. Born in Georgia and of Armenian descent, he made films about Ukrainian history. One can hardly find anyone who embodies the cultural pluralism in the title of the current exhibition "Kaleidoscope of History(s). Ukrainian Art 1912-2023" as much as he does. His film fragment "Kiev Frescoes" is part of the exhibition and was also featured in the digital prologue here on voices.