“Digital” means that something can be described as a series of numbers; a chain of states accorded values such as 1 and 0, on and off or yes and no. The term comes from the Latin word “digitus” (“finger”) and is related to the ancient technique of counting on one’s fingers. Such strings of digits have long been complex enough to be used to represent any medium. Thus, when the pandemic limited most possibilities for socializing offline, the digital world became the main venue for almost any social contact. At the Dresden nightclub “objekt klein a,” the entire premises were digitized for that purpose. Ironically, the club is actually named after “objet petit a,” the spot where, according to Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory, a fundamental absence is revealed: the lack of the Real. In Lacan’s theory, objet petit a is something like a wound that arises with human cultivation and reflects a world preceding that cultivation that is disordered, immediate or Real. Although it would fit well into the metaphor of our needs during the pandemic, in fact when Lacan speaks of the Real, he thus does not mean our everyday understanding of reality, but precisely the opposite: something that is missing from our reality and cannot be found in our world order. When we experience music and ecstatic dance of the kind depicted by the Greeks in their image of the god Dionysus, this is probably the closest we come to accessing the experiences that Lacan calls Real.

From March 5, 2022, objects from the Porzellansammlung, managed by Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, will now be on view at digital events held at the virtual objekt klein a. In an almost Nietzschean marriage of the Apollonian and Dionysian experiences of art, two things will be brought together in the digital world that would be almost impossible to unite offline. The fact that this will be happening in a place called “objekt klein a,” after the spot where human desire arises according to Lacan, is a match made in heaven.

Flyer zur Veranstaltung "mixed reality weekend society" im Virtual Club des objekt klein a.

© objekt klein a

According to psychoanalysis, after all, the lack of the Real gives rise to a kind of compensatory mechanism that instead makes people covet what their cultural order deems appropriate for them to desire. By definition, that can be almost anything but the Real itself. The German football manager Sepp Herberger famously said “After the game is before the game,” and the same applies to objects of desire: where one ends, the next begins—a simple principle that can equally be applied to partying or, of course, the acquisition of collectibles, depending on what subculture you belong to. The legitimate question of what all this has to do with porcelain can thus probably be answered in the spirit of the porcelain collector and infamous party host, Augustus the Strong: it has everything to do with porcelain.

Until the early 18th century, porcelain could only be obtained from the Far East. It had to be procured via extensive trade networks and was therefore extremely valuable and highly coveted by European princes. Porcelain was so closely associated with the country of its origin that “china” is a synonym in English to this day. Europe’s absolutist rulers saw themselves as needing to constantly display their status in the form of exquisite splendour; the Chinese were thus admired for this fine material that the Europeans long remained unable to produce. The delicate, translucent white stood for purity and perfection, its sheen reminiscent of the temptation sometimes felt at the sight of a pristine blanket of snow.

Vielarmige daoistische Gottheit Doumu, China, Dehua, 1675 - 1725.

© Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Adrian Sauer

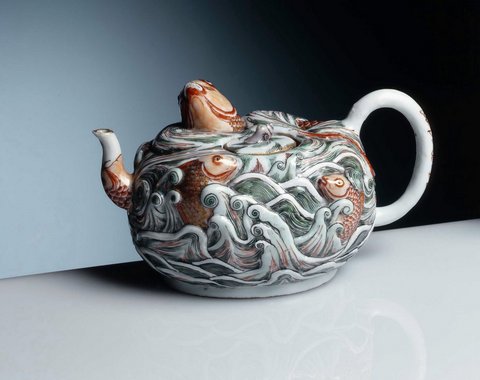

To European rulers, Chinese porcelain was therefore associated with a certain amount of humiliation. Their inability to produce a comparable material did not simply demonstrate their inferiority in terms of craftsmanship; it also meant they depended on imports from China, whose trading conditions and prices could be dictated to the Europeans. Collecting porcelain as a European was therefore regarded as a sign of financial and political means, and no one took the practice further than Augustus the Strong, the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland who, over his lifetime, amassed the largest specialist collection in Europe. Unfortunately, there are no records of how much Augustus paid for this curious Chinese teapot. Its special charm lies in the figural design on its body: reddish-gold fish leap over towering waves and the knob on the lid is in the shape of a shell. Augustus is unlikely to have understood the symbolic meaning this motif had in China. The fish depicted are carp, successfully swimming against the current of the raging Longmen River and transforming into a dragon—a symbol of success in the imperial examinations taken by mandarins.

Teekanne, China, Qing-Zeit (1644–1911), Ära Kangxi (1662–1722), um 1700.

© Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Jürgen Karpinski

When, under Augustus’s aegis, the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger and the natural scientist Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus eventually developed Europe’s first process for manufacturing porcelain in 1708/09, this political triumph was a bitter pill for the other European dynasties to swallow. August adroitly took advantage of this feat both economically and politically, bestowing gifts in a calculated manner to increase demand for porcelain while simultaneously drawing attention to his rank: these gifts that could not be reciprocated were a symbol of political power. His accompanying comment that they were nothing but “Saxon earth” took the gesture to further heights of empowerment. Augustus’s attempts to impress even the Chinese with presents of this kind did not, admittedly, provoke much of a response in the birthplace of porcelain. However, this did not stop him from confidently presenting the bespoke pieces made for him on the upper floor of the Japanisches Palais in an arrangement that was clearly intended to be hierarchical. Once visitors had viewed the Far Eastern collection on the lower floor, they climbed the stairs to admire the Saxon-made porcelain on the floor above.

With images of the variety and beauty of East Asian porcelain still in their minds, visitors’ gaze fell first on an entire menagerie of mostly life-size animal sculptures made of Meissen porcelain, including these intertwined dogs. They could surely not help but be amazed! These porcelain figurines could not be compared to any of the pieces imported to Europe from China and Japan in terms of either their size or complex shape. Even now, firing cracks and minor flaws in the white glaze allow us to understand what enormous technical challenges such colossal sculptures posed; they tested the limits of porcelain as a material. Another unprecedented aspect was the incredibly vivid depictions of animals, whose individual characteristics are captured in porcelain. The sight of the bulldog’s teeth sunk into the soft flesh of the Italian greyhound’s flank almost provokes a similar grimace of pained sympathy.

Johann Gottlieb Kirchner: Windspiel und Bulldogge im Kampf, Porzellan ohne Bemalung, Meissen, vor März 1733

© Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Juergen Karpinski

In China, this new approach to porcelain design may have caused no stir at all, but in Europe, the Saxon breakthrough was extremely significant. As a result, all manner of attempts were made to find out the processes used at the Meissen manufactory. Plans for kilns were secretly copied, manufactory workers were plied with liquor and enticed to work elsewhere. It was thus not long before porcelain was also being made in other places; the Saxon monopoly was only short-lived. From around the 1750s onwards, there was serious competition from the equally skilful products of the French Manufacture royale de porcelaine de Sèvres. Moreover, the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) had a decisive impact on Saxony’s productivity. The great economic success that Augustus had expected from the development therefore did not occur. Porcelain production was profitable despite the extensive sums pocketed by the king, but it was by no means sufficient to co-finance the state budget as had been anticipated. The gain in prestige, however, was almost impossible to measure in figures and thus, by definition, cannot be depicted digitally. The same applies to the value of the social aesthetic events at objekt klein a. It is therefore probably only a matter of time before, just like porcelain, digital nightclubs and exhibition spaces are introduced in other places; indeed, the process has already begun in Berlin, for example. Meissen porcelain cannot, however, be found in Berlin, as that particular brand goes back to Elector Augustus and the passion for collecting he himself once jokingly described as a “maladie de porcelaine.” The psychoanalyst Lacan would doubtless have appreciated Augustus’s self-diagnosis of his covetous malady.

Also of interest:

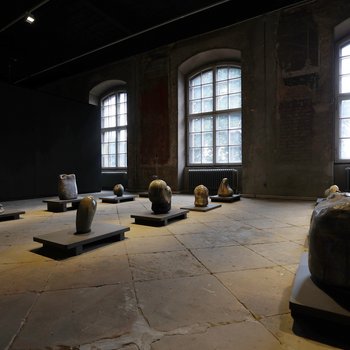

The firing of clay is one of the earliest technologies discovered or invented by man. A variety of work featuring ceramics as well as film and images created by Rome Prize winner Benedikt Hipp will be among the exhibits on display as part of the new exhibition “Eppur Si Muove – Und sie bewegt sich doch” at the Japanisches Palais (Japanese Palace), which happens to be the original location of the Porzellansammlung. In the following, Hipp offers insights into how he himself experiences and observes the creation of his ceramics – from collecting clay to the fired object.

What happens when you give museum audiences a stack of pencils, a few sheets of paper, and an entire room lined with white paper? Dresden artist Artourette did just that as a part of the Children's Biennale at the Japanisches Palais.

As time goes by, contemporary art too is aging. Often one has to deal with works that are ephemeral and perishable, as well as time-based media and materials. We’ve spoken to Franziska Klinkmüller, the conservator in charge of the Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, about the challenges of restoration of contemporary art and aspects related to sustainability.

![[Translate to English:] Ernesto Neto, the house, 2003, exhibition view Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/e/csm_IMG01_Neto__Ernesto__the_house_SHO__01056_99_9fe9d0bcc4_22a5412168.jpeg)