In May 1965, the Polish lifestyle magazine Ty i Ja praised fitted kitchens: ”One of the tendencies of modern domestic architecture has been an integration of an entire apartment with what we used to call the kitchen. The kitchen has gradually been transformed into a laboratory; it has stored more and more appliances with styles to suit every taste. Why shouldn’t we therefore think — remaining obstacles, including ventilation aside — about including the kitchen into the normal living area? To transform it into a niche, an annex linked to the living area instead of treating it as the sphere of an enslaved housewife. Additional contributions to the emancipation of this hitherto isolated space are the fact that even men now work in the kitchen, and the lack of servants.” Three years earlier, the magazine had argued that ”a kitchen is not a shameful space”. Within the contemporary social structure, it clarified, in which a servant has become a relic, the kitchen had become a family’s domain and a housewife’s workplace.

Spoon Archaeology - Complexity Map (Detail)

© Peter Eckart, Kai Linke, Dylan McGuire, Lukas Loscher

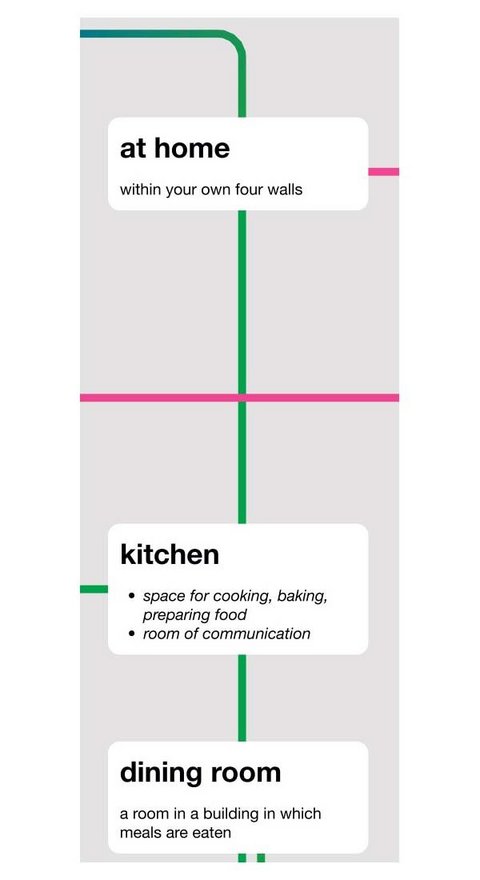

The emancipation of the kitchen as understood in this quotation was threefold. First it meant social emancipation and, quite literally, the disappearance of servants. Obviously, in the People’s Republic, where Ty i Ja was published, there was no room for the bourgeois and aristocratic habit of having domestic staff; but the tendency was widespread across Europe and anything but new. In his book Home: A Short History of an Idea, Witold Rybczyński explains why the kitchen acquired its central place in 17th century Dutch homes with the decreasing number of servants and the transformation of homes into the workplace of housewives. While back in those days in other European countries, kitchens were virtually separate from the rest of the dwelling and rather neglected, in the Netherlands, they played a leading role and housewives took special care of them. This is quite under- standable. As long as the kitchen is a place exclusively devoted to servants who have no say, nobody takes an interest in improv- ing it. But as soon as a housewife occupies it, she takes good care of the space, makes generous investments and integrates it into the rest of the home.

In Europe between the two World Wars, the introduction of modern, compact kitchens with a clear connection to the living space also had much to do with progressive social ideas and the disappearance of servants. Barbara Brukalska was an architect who designed kitchen-laboratories for a social housing project, the Warsaw Housing Cooperative. On closer inspection, her drawings show a fashionable lady with a pixie cut working in the kitchen. She definitely is not a servant but a modern working woman who has a job outside the home, maybe the architect herself. Indeed, the architects of the Warsaw Housing Cooperative didn’t provide for any special rooms for servants in the progressive, modern but modest apartments they designed. Nonetheless, their middle class occupants were not very keen to abandon their habits and kept domestic service anyway. Since there were no rooms assigned to the servants, they were forced to live in basements, attics, garbage dumpsters or even sleep in bathtubs. Still, the gradual disappearance of servants was a fact, and it had a huge influence on the designs of modern kitchens. Design historian Adrian Forty commented on the idea that domestic appliances were invented as a response to the decline of the servant class. He noted that this idea has been repeated so many times that it’s finally become a widely accepted fact, which came in handy both to housewives and to manufacturers of domestic gadgets and equipment.

The emancipation of the kitchen also meant an emancipation of women themselves. Initially, however, the ideas for comfortable, labour-saving kitchens didn’t question traditional gender roles. Christine Frederick, an American, was a pioneer of scientific management in the kitchen. Inspired by Frederick Taylor’s ideas, to which she was introduced by her husband, she elaborated a precise methodology of time- and energy-saving kitchen design. Her design process was based on research. In her studio-kitchen she conducted experiments with step-saving food preparation processes and investigated hundreds of kitchen products. Her meticulous calculations of the time needed to perform different tasks resulted in a significant rationalization of a woman’s work in the kitchen. The time saved on daily chores could be used for the benefit of the family. Frederick’s book The New Housekeeping (1912) was extraordinarily influential. It was translated into six languages and widely cited by members of the European avant-garde. However, the aesthetics of Frederic’s kitchen was still quite conservative, and so was her motivation.

Spoon Archaeology - Complexity Map (Detail)

© Peter Eckart, Kai Linke, Dylan McGuire, Lukas Loscher

Eventually, a modern, hygienic fitted kitchen-laboratory was developed in Europe within the context of functionalism and the concern for social welfare. Barbara Brukaska’s kitchen in the Warsaw Housing Cooperative is a good example, as it was de- signed as part of the utopian programme of working-class housing and eventually became available for wealthier inhabitants. In Germany, new kitchens were developed as a means to free women from the drudgery of the kitchen and allow them to work outside the home. The most successful realisation of the kitchen-laboratory was the ”Frankfurt Kitchen” designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, a devoted reader of Christine Frederick’s work and an enthusiast of household engineering. This kitchen was developed for a social housing project designed by Ernst May in Frankfurt and eventually was installed in ten thousand apartments. The architect’s motivation was clearly progressive. She claimed that ”the struggle of women for economic independence and personal development meant that the rationalization of housework was an absolute necessity.” Schütte-Lihotzky managed to combine household engineering principles with a highly modern aesthetics and laid the foundations for all later fitted, compact kitchens. The scientific look of these kitchens didn’t mean that their architects avoided decisions relating to their styling. Adrian Forty remarked that the middle classes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries became increasingly concerned with cleanliness, which explains the extraordinary success of hygienic spaces, white and smooth, seamless, easily cleaned surfaces. Contrary to this tendency, some of the most influential female designers decided to use colour in their kitchens. Frankfurter Küche had a number of variations and some of them included furnishings in plain, cold colors like blue and green hues. Much more colorful was a compact kitchen designed by Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier for his Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. The flat panels used for furnishings came in different colors, forming an abstract geometrical composition.

This exploration of scientific home management was illustrated in Kitchen Stories, a film directed by Bent Hamer. The opening scenes show a laboratory where the subjects and their performances are meticulously timed in order to optimise kitchen design. Then a researcher is sent to the field with a mission to put a single male un- der investigation. This is where the funny part starts: clearly, the kitchen-laboratory was designed for women. Nevertheless, Penny Sparke, a design historian, argues that architects such as Brukalska or Schütte-Lihotzky were in fact agents of ”male” aesthetics with its functionalist and modern look and scientific approach.

A more ”female” outlook can definitely be found in the post-war American kitchen with a stereotypical domestic goddess in stiletto heels surrounded by streamlined household appliances. This spacious kitchen was also suited to serve as the epicentre of family life, as a journalist observed in Time Magazine in 1954: ”Since the war, whole houses are virtually being designed around colorful, labor-saving kitchens that can also serve as an all-purpose living space for the family.” This abundance of colours was stimulated by the domestication of new materials, especially plastic. The plethora of different colours and shapes of Tupperware dishes are a good example of this plastic revolution. Modernity and progress not only meant that man could go to the Moon, but also that the American housewife could aspire to the gadgets of her dreams. In 1956, General Motors published a promotional film, Design for Dreaming. The main character, an svelte dancer, is taken to a spectacular car show and an even more spectacular ”Kitchen of the Future” which saves the lady’s time not by scientific engineering but by mechanisation by a masked man.

The lady is delighted to find she has plenty of time for entertainment. In fact, American post-war kitchens were anything but compact and were demonstrations of abundance and prosperity. They also were the arena of the activities of professional housewives, the place where women could spend their day taking care of their families and homes and chatting with lady neighbours, who also did not work. At least this is the image evoked by pop culture, where frus- trated women spend their idle hours in their beautiful kitchens, either chain smoking (Mad Men) or planning their escape (The Hours).

The first secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev, had a similar image of women in the American ”wonder kitchen”. It became a strange battleground in the Cold War competition. In 1959, after the USSR had launched its first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, the United States organised the American National Exhibition in Moscow. The Americans were fully aware of the fact that they were losing the Cold War competition on the military and space fronts, so they decided to outpace their enemy when it came to the quality of everyday life. The exhibition therefore showed a plethora of American consumer goods with a spectacular ”wonder kitchen” as one of the main attractions. This was the setting of the famous confrontation of the two leaders of the superpowers, Khrushchev and Richard Nixon, known as the Kitchen Debate. Nixon was very proud of this demonstration of wealth and innovation, but Khrushchev was not an easy adversary. He accused American culture of keeping women in the “golden cages” of their huge kitchens while Soviet working women were given compact kitchen-laboratories which saved them time and eventually contributed to their emancipation. “I feel sorry for Americans,” said Khrushchev, “judging by your exhibition. Does your life really just consist of kitchens?“ The intelligent Soviet leader presented the small, modest kitchens in small and low-quality mass housing as tools for emancipation. He didn’t quite go as far as Lenin himself, however, who had proposed in the 1920s to abandon kitch- ens in general and to replace them with collective dining. In Khrushchev’s kitchen, the one who cooked still was a woman, a working woman who, as a result, had two jobs: one outside the home and one in her kitchen.

The real emancipation of the kitchen may ultimately be the emancipation of the very space which became possible thanks to the advent of clean fuels (gas and electricity) in Western Europe and the US after World War I. The author of the article quoted at the beginning proposed to connect the kitchen with the rest of the home. This space would become the heart of family life. After the war, eating in the kitchen became a widely accepted habit. In small apartments, there was no room for a big table and a separate dining room. Small dimensions prevent- ed the inhabitants from sleeping in the kitchen, a common habit before the advent of efficient central heating as the kitchen used to be the warmest in the house. In the following decades, when aesthetics and sophistication of kitchens allowed it, they became directly connected with living rooms. Preparing food and cooking was exposed and cooking became a social activity, even a performative one. What might be the next step of the emancipation of the kitchen? Does an emancipated kitchen necessarily have to be a fitted one? Or could it emancipate itself from the given space and be taken somewhere else, even outside the home?

Also of interest:

Disposable plastic cutlery is an icon of the global throwaway culture. It has been banned in the EU since July 3, 2021. Based on the collection of designers Peter Eckart and Kai Linke, the exhibition "Spoon Archaeology" at the Kunstgewerbemuseum explores this topic.

The Spoon Archaeology exhibition is designed as a reaction to the EU ban on single-use tableware. But what will replace it? The designers Peter Eckart and Kai Linke, whose cutlery collections are on display in the Kunstgewerbemuseum this year, asked themselves that very question. It has to be sustainable and, of course, fit for purpose. The answer they have come up with has a far less futuristic ring to it than you might expect: the human hand. We join the Palais Café to try it out.

With an extensive restoration at the Kaiserzimmer – previously known as the Weinling-Zimmer – this important suit of chambers, located in the west wing of the Bergpalais, Schloss Pillnitz, is again part of the visitors’ trajectory at the Kunstgewerbemuseum. Now that these outstanding rooms of early neoclassical style shine again in their former glory, they also attest to a history full of turns. Christiane Ernek-van der Goes on the cultural history of this masterwork. A reprint from our blog.

![[Translate to English:] Kaiserzimmer, Bergpalais at Schloss Pillnitz, 25.08.2020](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/d/csm_Img010_Kaiserzimmer_5bf21e4a94_d1dcac238d.jpg)