When is the intensity of time most acutely felt? The night is long in the face of insomnia, and yet days can go by in the blink of an eye. When time is running out, our hearts race and our breaths hasten. In meditative contemplation, time slows to a halt, as our minds and bodies settle into calmness. Time is deeply felt in our physical bodies. We take note of its unfaltering progression through day and night, as the earth rotates around the sun, and the moon around the earth, bringing cycles of light and darkness to our lives.

Yet, how do the textures of felt time shift as time becomes punctuated by imposed rhythms of the clock? Through the technology of time measurement, signaling, and management, time is segmented into calculable units of hours, days, and weeks, which becomes the basis upon which our lives are organised. Consequently, we are no strangers to wage labour compensated by the hour, nor to timetables and schedules that dictate what time we need to wake up and go to work. As time technology advances, we are even used to real-time tracking that shows food delivery travelling through the city with a rider, and to self-tracking wearables and apps that visualise and analyse our cycles of sleep. Speed, rhythms, and routines are trackable 24/7, providing the opportunity for utmost efficiency and optimisation.

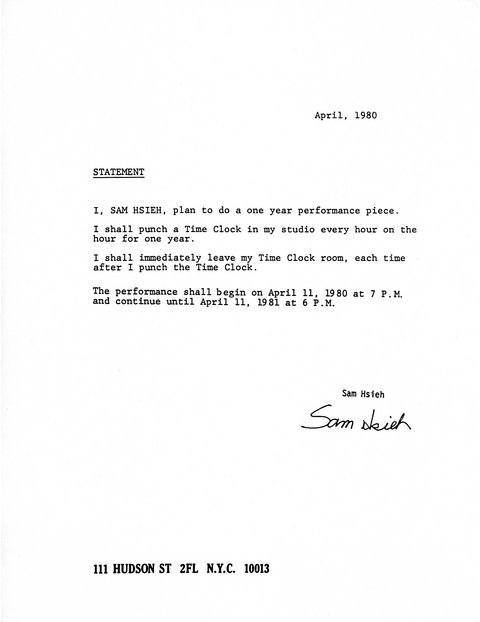

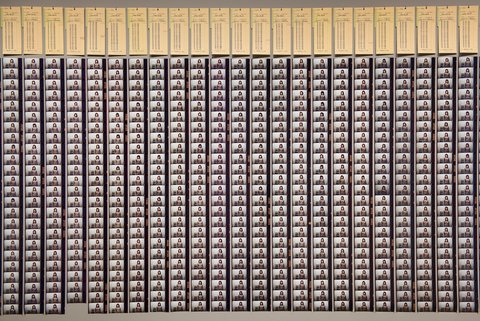

A by now classic piece of performance art that investigates our corporeal relationship to time technology is Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980-1981 (Time Clock Piece). In this durational performance, Hsieh installed a fully functional worker’s time clock, a lighting system, and a camera suspended from the ceiling facing the clock inside his studio. He signed a contract in which he stated, “I shall punch a Time Clock in my studio every hour on the hour for one year.” For 365 days, he clocked in using punch-card technology every day, every hour on the dot, 24 hours a day. Because of this tight schedule, he was confined to his studio space and its immediate vicinities, and could not even rest continuously for more than fifty minutes. He meticulously recorded his time-stamped cards and took hourly photos next to the time clock. The archive, after the full year, shows that he was only unable to perform 133 of the 8760 clock-ins. The successful 8627 clock-ins produced recorded images which were then condensed into a time-lapse film, essentially compressing his entire year into 6 minutes.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980-1981 Statement

© Courtesy of the artist

The worker’s time clock functions as a surveillance device, as Hsieh’s work performatively reveals how the invention of clock-time as a technology harnesses human bodies as a resource for labour. He stood in front of the camera as it captured, almost in a ritual-like manner, his stoic face every time he clocked in, a face that gazed back into the emptiness of a life arranged purely for the extraction of labour. Clock time is felt intensively through its inescapable mechanisms of control. Each punch-in is a literal punctuation of time – was he too early, or too late? Was he right on time or was he absent? Each punch-in reinforces his agreed hourly labour terms, signed and sealed on a contract. But each punch-in is also a puncture that marks the brutal withdrawal from the possibility of rest. From this perspective, Hsieh’s work exposes the violence that time-managed labour could impose upon the body. By forcing his corporeal self into the cold rigid regularity of clock time, and by subjecting himself to the surveillance of punch-cards and a camera, he makes visible the rhythmic bind of the machine, 24/7.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980-1981 Installation view

© Photo by Hugo Glendinning, Courtesy of the artist

As such, Hsieh’s work prepares us for a world of control and surveillance based on time technology and labour. In Out of Now (2008) - a critical overview of Hsieh's artistic career - Adrian Heathfield reads the performance as a “systematic critique of the temporal logic upon which the social and cultural organisation of late-capitalism is founded” (32). Even though the work is pre-digital, it encapsulates the modes and technologies of capture that we now recognise as digital surveillance. In today’s terms, Hsieh essentially created a performance of durational self-tracking, and presented himself as a quantified and datafied subject. While he based his piece on the mechanisation of time stemming from the industrial age, recalling the factory worker in the mass production lines of industrial capitalism, his work still finds relevance today in the digital regimes of time management. Here, I am reminded of the Amazon warehouse pickers racing to compile orders under the surveillance of wearable computers on their arms, and of the runners in dark stores compiling app-based grocery deliveries to make sure the order gets to someone’s door in 15 minutes. Much like the clock punch-ins, these workers are forced to work at rhythms mediated and dictated by digital apps, logistics, and the desires of global commerce. The worker’s time clock has turned into digital pings and beeps of app alerts and real-time surveillance technologies.

Jeremy Deller Motorola WT4000 Wearable Terminal, 2013 Plastic and electronics Installation view ‘All the World’s Futures’, Venice Biennale, Venice, 2015

© Courtesy of the Artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow Foto: Cristiano Corte

Time Clock Piece prefigures the intensity of a 24/7 world in which capitalist systems of consumerism are always online and logistics drive the engines of labour. More importantly, the performance makes the intensity of capitalist labour time felt. What are the effects of working according to time arrangements inside Amazon’s warehouses or based on speed delivery apps? What are the effects of living in such a regime of time? As a spectator, I often wonder what happened after the One Year Performance ended on April 11, 1981, at 6PM. Beyond the evidence of punch cards and photographs, how did Hsieh’s body measure and record the duration of that year? Did he sleep for days on end, or did he need to relearn how to sleep for longer durations? Did the experience train his body into recognising the interval of an hour better than the rest of us? Or did it leave a permanent blotch on his physical and mental health? What we know for sure is that his hair grew into unruliness and his eyes grew saggier by the day under the weight of sleeplessness. We can only imagine what other strains and stress the experience presented. In his clock-driven year, Hsieh’s body revealed to us the burden of living and labouring under capitalist time, and is perhaps a forewarning against the quantified and datafied subjects working under digital surveillance regimes today.

One Year Performance 1980-1981 can can be seen until 17 February daily from 0-3 and 12-15 (CET) here.

This text is part of the exhibition “Feeling time. Experiences of temporality” (9.12.2022-27.2.2023), curated by Jane Boddy and Michael Griff.

Also of interest:

Disposable plastic cutlery is an icon of the global throwaway culture. It has been banned in the EU since July 3, 2021. Based on the collection of designers Peter Eckart and Kai Linke, the exhibition "Spoon Archaeology" at the Kunstgewerbemuseum explores this topic.

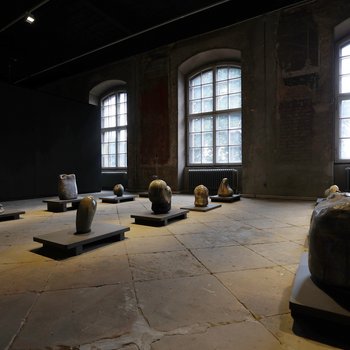

The firing of clay is one of the earliest technologies discovered or invented by man. A variety of work featuring ceramics as well as film and images created by Rome Prize winner Benedikt Hipp will be among the exhibits on display as part of the new exhibition “Eppur Si Muove – Und sie bewegt sich doch” at the Japanisches Palais (Japanese Palace), which happens to be the original location of the Porzellansammlung. In the following, Hipp offers insights into how he himself experiences and observes the creation of his ceramics – from collecting clay to the fired object.

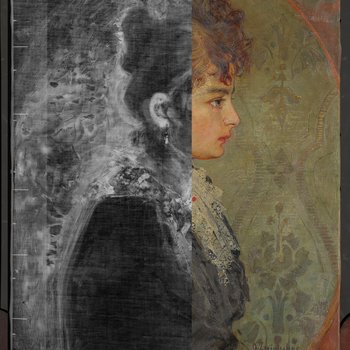

Seventeen works from the artist’s oeuvre – which originally comprised around 150 paintings – were examined in the research project “Oskar Zwintscher (1870–1916). The Unknown Masterpiece” by the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in the Albertinum, funded by the Friede Springer Stiftung, subjecting them to art technology analysis in the painting restoration workshop. Here you can gain insight into the complexity found in the structure of Oskar Zwintscher’s paintings.