The depth of the ties between Japan and the GDR is matched only by the lack of research on the subject today. The two countries developed a multifaceted relationship. Japan was seen as an economic bridge that would link East Germany’s socialist system to the capitalist West, hopefully offering opportunities to strengthen the GDR’s position with regard to foreign affairs and help it exert an influence on West Germany. Chancellor Konrad Adenauer had, after all, set out the “Hallstein Doctrine” in a statement to the German parliament in 1955. Designed to protect West Germany, this stated:

“(…) that the Federal Government would continue to see it as an unfriendly act if third states with which it (West Germany) maintains official relations also establish diplomatic relations with the German Democratic Republic.”

Shogo Akagawa, Die Japanpolitik der DDR, 1949 bis 1989, Berlin 2020, S. 32.

For this reason, potential trading partners on the side of the West tended to be cautious when it came to relations with the GDR. The latter was, moreover, subject to the 1950 CoCom Embargo, a US-led trade embargo that prohibited the sale of new technologies to Eastern bloc countries.

The GDR began to seek economic relations with Japan after the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. Taking in the Japanese economic miracle during the Games, members of the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) came to see Japan as a potentially lucrative partner alongside Canada and the USA and wanted to foster international relations with the country. However, their plan met with an initial obstacle in that Japan felt committed to Adenauer’s doctrine. To spark Japanese interest in the GDR, East German cultural policymakers tried to present the country as the true “heir to German culture”. This included guest appearances by East German orchestras such as Leipzig’s Gewandhaus Orchestra and Dresden’s State Orchestra. Classical music enjoyed great popularity in Japanese culture at that time, so the GDR’s orchestras were often invited to play in Japan.

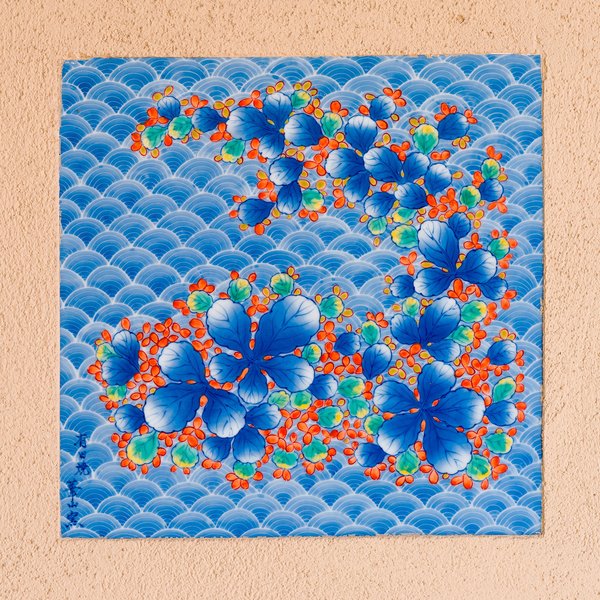

Newspaper clipping, Masterpieces Paintings, Japan 1974

© Press Archive SKD

1 Shogo Akagawa, Die Japanpolitik der DDR, 1949 bis 1989, (Studien des Forschungsverbundes SED-Staat an der Freien Universität Berlin, Band 28), Berlin 2020, p. 312.

2 Exhibition Website (last accessed 30 Nov. 2023))

3 Akagawa, 2020, pp. 312/317.

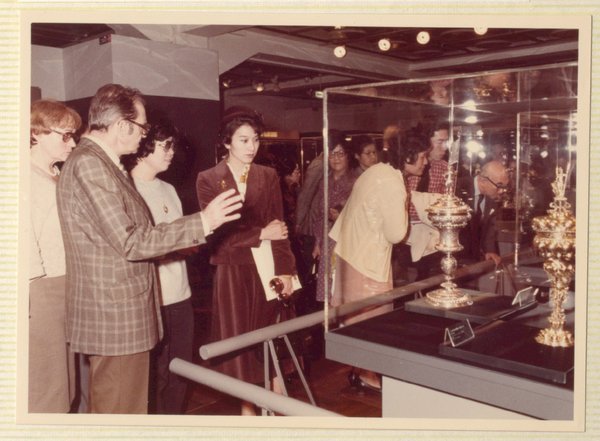

Johannes Erhard Schöbel and actress Komaki Kurihara at the Mitsukoshi Contemporary Gallery, Japan 1979-1980

© Press Archive SKD

4 The exhibition took place in Tokyo from 30 October to 18 November 1979, in Osaka from 27 November to 9 December 1979, in Hiroshima from 29 December 1979 to 19 January 1980 and in Fukuoka from 19 January to 17 February 1980.

5 Exhibition catalogue. Modern Japanese Lacquerware, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 1982, foreword.

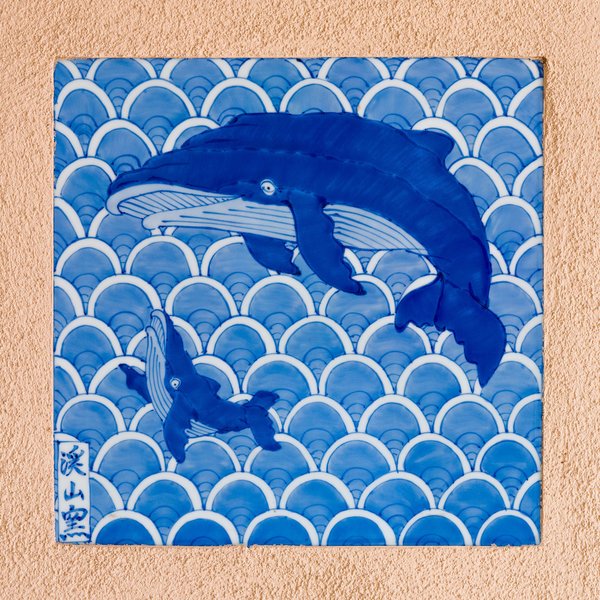

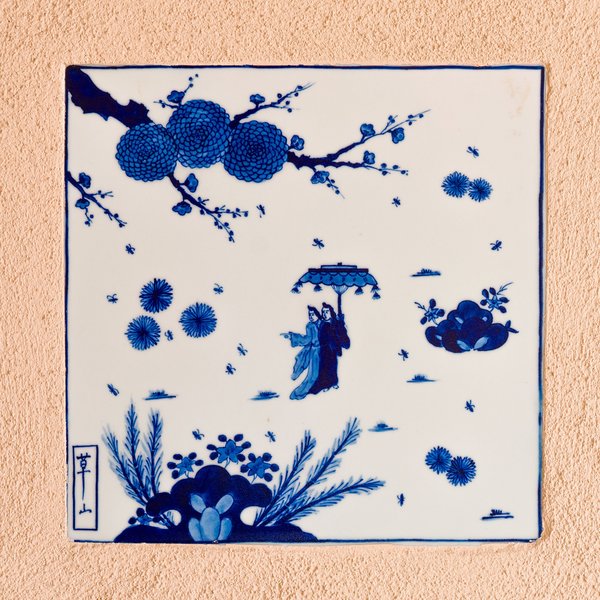

Porcelain plaques from Arita, Japan in Meißen

© Jacob Franke

6 Exhibition catalogue. Three Millennia of Japanese Art, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 1974, pp. 13–14.

7 SKD archives, D2/PS 72, Invitation to a joint consultation on 8 August 1980, p. 2.

8 SKD archives, O2/vw51, Administrative director’s office 1975–83, Travel report by Mr Rost, 15 April–5 May 1975, Japan, p. 2.

9 SKD archives, 428/91, Sächsische Zeitung 14 October 1975 (newspaper clipping), “Japan sprach von diesem Porzellan”, interview featuring Toshimitsu Fukuda and Dr Georg Kretschmann

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 SKD archives, O2/vw51, Administrative director’s office 1975–83, Travel report by Mr Rost, 15 April–5 May 1975, Japan, p. 1.

Keep reading:

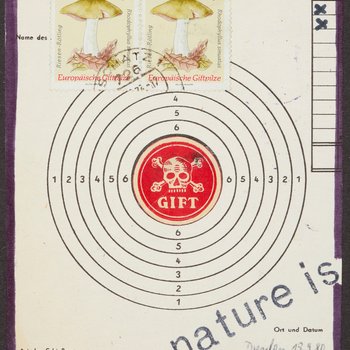

Starting in the 1970s, a type of artistic dialogue developed in East Germany that took place not in museums and galleries but, instead far from the world of public exhibitions, via the postal service. Soon after, the Dresden artist Birger Jesch launched what he called the “first Mail-Art Project of Dresden”, posting 300 cards featuring shooting targets to recipients around the world, for them to design and return.

For the “Counterpoints” project, the SKD are studying the international history of the East German cultural sector - a project about the history of their own collection; about dialogue and networking. Above all, however, it is about correcting the narrative describing that history as provincial and isolated from modernism. In June, TU Dresden’s Chair of Visual Culture Studies in a Global Context organised a conference on the ties between the GDR cultural sector and the Global South, working with the Albertinum and the TU Office for Academic Heritage, Scientific and Art Collections.

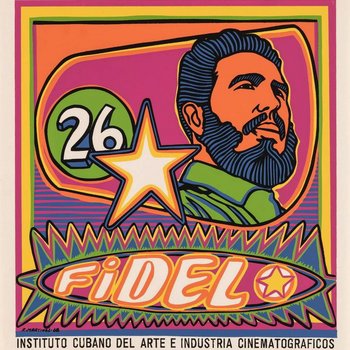

The Kupferstich-Kabinett is home to a significant collection of Cuban prints and posters that came to the GDR after the Cuban Revolution in 1959. While they were earmarked for the collection as part of the cultural exchange between the two socialist states, its director often did not welcome them with open arms. Olaf Simon, conservator at the Kupferstich-Kabinett, wrote about how they came to be part of the collection.