We are living in the “Age of Crisis.” There is not a single sphere of our lives that has not been disrupted. It seems like we wake up to a new impossible crisis every single day: democracy, economy, climate, migration, privacy, technology and information, you name it! Then, to add insult to injury comes the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented global health crisis that brought the world to a halt. We are witnessing a bad time, with the promise of much worse to come. Scientists are proving day-in-day-out how human’s broken systems, for the sake of progress and prosperity, are actually destroying the Planet. At a speed and dimension, we can barely comprehend. The broad consensus is that we are in for a big crash! And we have no idea how to stop it from happening. The problem is, some of us are getting used to it. Thinking, “it is what it is”, and throwing the towel. Understandably. “The overlapping crises have had an erosive effect on all of us; on our nerves, hope, and resolve,” reflects the acclaimed Design Curator Paola Antonelli. “Time to reboot.” But how? There is no reset button to end this madness. But there is hope in collective action and rewiring. There has to be hope and optimism to think creatively about the future. Fear, mostly, paralyse us. This was the main reasoning behind our vouch for utopia in the newly founded Design Campus and its Summer School.

William Morris, News from Nowhere (1890),

© Creative Commons. Written by the William Morris, who led the Arts and Crafts Movement, News from Nowhere is a utopian representation of an ideal society. "Nowhere" is in fact a literal translation of the word "utopia". His utopia visualizes a society where people are free from the burdens of industrialization and therefore they find harmony in a lifestyle that coexists with the natural world.

Utopia is a powerful idea. Visionary, unrealistic ideas are what steers the world forward. It was the dream that we could fly, cure diseases, have telecommunication, discover faraway lands or live in more equitable societies that drove men and women to take risks and design our way till here. “All utopias ask questions. They ask whether or not the way we live could be improved and answer that it could. Most utopias compare life in the present and life in utopia and point out what is wrong with the way we now live, thus suggesting what needs to be done to improve things.” Says Lyman Tower Sargent in his seminal book Utopianism. “Utopianism is social dreaming,” he explains.

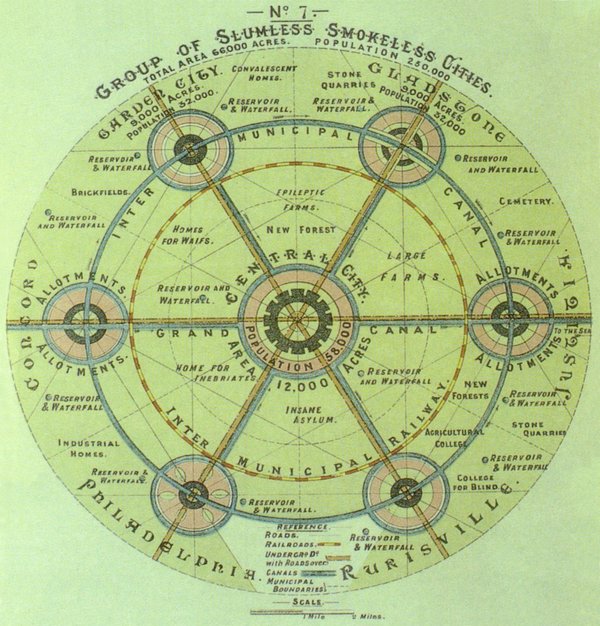

Design history is steeped in utopian thinking. From the beginning of industrialisation, designers have been concerned with social causes and quality of life. For example, the Arts and Crafts Movement, led by William Morris, dreamt of a better society by promoting a return to nature and handcrafted objects to counteract the advances of industrialisation in the 19th century. The modernism of the 1920s and 1930s gave rise to social housing ideas of Le Corbusier, the intense social programs of Moholy-Nagy, and the complete adoption of industrial technologies as a basis for creating functional products and houses taught and developed by the most famous design school in the world, the Bauhaus. After World War II, with the advent of postmodernism, came the decline of utopian beliefs as a reaction to totalitarianism, social repression and the vast environmental problems caused by the inconsequential belief in technical progress. The postmodern ideal became the promise of boundless human plurality, adaptable products and acceptance of any singular way of living. Individualism and customisable products are a result of postmodernism. Nowadays, with the pervasive digital technologies and collapse of the environment, how should we reimagine the future?

Design has a fundamental role as an agent of change in society – social, political, economic, scientific, technological, cultural, ecological. More than ever, with the impacts of digital technology in our daily lives, we are able to understand the superpower of design. It is certainly not only the capacity to embellish and sell more products. It is the power to change behaviour. In a massive way. For better or worse. Think about it. How was your life before 2007, when the first iPhone came onto the market? We can barely remember life without smartphones. Designers should be aware of this power. And be responsible for it.

There is no more room for unintended consequences of “good” design. And no simple answers for complex and systemic problems. Within this critical context, the Design Campus and its Summer School was conceived at Kunstgewerbemuseum as part of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

The Kunstgewerbemuseum focuses on applied arts, craft and design. Museums as such were first envisioned as training and trendsetting platforms during the first industrial revolution. Training professionals, industrialists and the public, eyes and taste, alike on what “good design” or good industrial products should be. These museums were attached to schools, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and the Royal College of Arts in London, and the Museum für Angewandte Kunst (MAK) and the University of Applied Arts, die Angewandte, in Vienna. Museums of Applied Arts were not meant to be contemplative museums like art museums, for example. On the contrary, they were meant to set standards and even, dare I say, set a political, social and economic agenda. Such museums highly promoted the consumerist lifestyle that supported industrialisation and capitalism. Museums are, therefore, part of the problem. Can we be part of the solution?

“With the Design Campus, the Kunstgewerbemuseum is returning to its roots as a teaching and educational collection, almost 150 years after it was founded. At that time, a reaction to the upheavals of industrialisation, the founding concept will be recalibrated for the 21st century against the background of social transformation through digitisation and climate change and thought into the future – as a place and a school for utopias,” says Thomas A. Geisler, Director of the Kunstgewerbemuseum. The Design Campus as a curatorial-driven, interdisciplinary, and future-oriented platform for rethinking the world’s biggest questions through design practices and culture. As a space for recalibration, education and empowerment of creative practitioners to take action on the many changes, challenges and uncertainties of the 21st century. And the Design Campus summer program as a “School of Utopias” – a visionary design school set to explore complex problems, dream bold ideas, and collaboratively build new ways forward.

The premise of the Design Campus framework is that we believe in the power of design to change the world for the better. But no discipline alone will heroically solve the world’s crisis. So, first and foremost, we embrace complexity. And accept that to untangle this mess, we need to break silos and collaborate intelligently, joining forces and knowledge from different disciplines. On top of that, we believe it is time to take on responsibility. It is your turn, and mine, to care. And above all, to act!

Design education, knowledge exchange and research are paramount for purposeful action. This, we believe, would be the way to engage with the world and tackling wide-ranging problems such as the climate emergency or the global pandemic we are facing now. By committing to a utopian vision, we do not intend to dismiss reality at all. Utopia, by definition, will never be achieved. However, it could certainly serve as a tool to reimagine better futures forward and allow us to take steps in the right direction.

![[Translate to English:] Brasilia, Pilot Plan Map, © Creative Commons [Translate to English:] Brasilia, Pilot Plan Map, © Creative Commons](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/4/csm_Abb7_Brasilia_Pilot_Plan_Map_Brazil_e30acaa67c.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Brasilia, Satellite Image [Translate to English:] Brasilia, Satellite Image](/fileadmin/_processed_/c/6/csm_Abb8_Satellite_Image_Photo_Brasilia_2cefd11fd5.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Design Campus – © Bureau Nardin [Translate to English:] Design Campus – © Bureau Nardin](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/6/csm_Abb2_Design_Campus-2_d0d31e59c4.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] The Design Campus of Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in August 2021 at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Pillnitz Palace. [Translate to English:] The Design Campus of Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in August 2021 at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Pillnitz Palace.](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/d/csm_180821killig007.1200x0_1ddf455ee4.jpg)