Live Speaking as a communication strategy in the exhibition „Völkerfreundschaften“

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Using the example of the GDR history of the Leipzig GRASSI Museum of Ethnography, the exhibition ‘Völkerfreundschaften’ (International Friendships) links central aspects of recent East German contemporary history with transnational and transcultural aspects.

From March to May 2024, four live speakers from the Leipzig GRASSI Museum of Ethnography investigated the connection between the Ethnographical Museum and urban community in the past and present. In the project, they developed artistic works that also reflect their own activities as Live Speakers at the museum. Using three exhibition objects - the deer dance mask from Mexico, the replica of a tepee by the club IG Mandanindianer Taucha-Leipzig e.V. and a female figure from the Iny Karajá indigenous society in Brazil - they brought together different opinions, positions and memories from urban society.

The result of the project is a polyphonic picture that combines autobiographical and transcultural perspectives and stories to create objects and exhibitions. The project takes the (recent) past of the GRASSI Museum of Ethnography as a starting point to reflect on the social role of ethnological museums in the present and future. Embark on a virtual journey and gain insights into the communication method of Live Speaking.

Uli Reible is an art historian and cultural scientist. She has been active as a Live Speaker at the GRASSI Leipzig Museum of Ethnography since 2022.

As a part of my tasks, I provide insights into museum work and give backgrounds on the exhibitions. I use my own expertise to give visitors more knowledge and context for certain exhibition areas. Sometimes I collect feedback by visitors for the museum.

The display ‘Völkerfreundschaften’ can be found on the 2nd floor and is the last room of the exhibition. My own experience has shown that the readiness to talk is smaller and the time spent by guests is often shorter here.

Some people are more reluctant towards us, because they do not expect to be engaged in a conversation. That is why we have developed certain tactics to start a conversation. I like to introduce myself and the concept of Live Speaking at first; all the while I remain close to the visitors, without becoming intrusive. When people enter the exhibition a bit disoriented, I ask, if I can help.

The work of a Live Speaker is challenging and enriching. It is about more than the dissemination of knowledge; it requires sensitivity and tactfulness in the interactions with other people. My goal is to give the visitors questions to take home and open new perspectives for them. Conversely, I am also very interested in their impressions and views.

I view Live Speakers as a part of the ‘REINVENTING’ process: I often explain, why the museum is changing and why that is important. I talk to people about the museum’s history and the purpose of a museum. I also often communicate knowledge about the colonial history of the collection.

Marita Caroline Meier is an ethnologist and visual artist. She has been active as a Live Speaker at the GRASSI Leipzig Museum of Ethnography since 2022.

In her artwork “How do we engage with the exhibited (object)?” she examines the different perspectives on meeting objects in ethnographic museums.

As a Live Speaker, I take on an interactive part in the ethnographic exhibition. I view objects through my own perspective of a student of ethnography and freelance artist, but also through the eyes of the visitors.

Over a period of three months, I have consciously examined and documented my work at the museum. The result is a collage – an abstract body as a medium for dynamics and diverse voices, resulting from the conversations about the exhibition ‘Völkerfreundschaften’ at the museum and a focus on the deer dance mask.

The layers of paper are metaphors for captured opinions, documentations of my own research on the deer dance mask and reflections of the museum experience. They are notes, sketches and painterly processings of this time. Stacked in layers, they represent the layers through which we view a seemingly neutral object.

Caroline Meier: Collage, 2024

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The deer dance mask originates with the group of the Yoeme and Yaquí and was originally used in connection with hunting. In my opinion, the mask is interesting for two reasons:

On the one hand, the deer dance of the Yoeme community in what is today Mexico describes a historical practice, which was subjected to changes and influences by the colonial and neo-colonial rule. Through mission attempts by the Jesuits, Christian elements have flowed into the deer dance. This expansion of meaning allowed the Yoeme to retain their own customs despite colonial occupation. Within the deer dance, pre-Hispanic religious practices coalesce with Christian iconography into new forms.

On the other hand, an anti-imperialist ethnographic research focus in the GDR plays an important role in its selection as an object in the ‘Völkerfreundschaften’ exhibition. Both aspects were put into focus in the conversations with visitors.

Visitors were always interested and curious about the symbolic meaning of aspects of the deer dance mask, like the red cloth around the antlers and its history. In terms of colour, the symbolism of the deer dance mask plays a distinctive role in the collage as well: Red as the connection to the living animal and its sacrifice during the hunt and simultaneously its metaphorical meaning of the spilled blood of Jesus Christ. The red band inspired me through its ambiguity – a symbolic red string, which pervades the different meetings and notes in my research – to include it in the collage. The red is a metaphor, which connects the different layers of meaning of the deer dance.

The selection of the deer dance mask marks a special feature of the GDR history of the museum. Compared to the ethnographic museums in Western Europe and the USA, the focus of the collection and exhibition was on the rights of indigenous groups and their resistance against colonial violence and conquest. The attention on the objects of indigenous communities corresponded to the Marxist research focus on class warfare and economic and social questions of ethnography. Visitors, especially former residents of the GDR, are touched by the portrayal of the rarely thematised GDR history. They stress, especially this specific aspect of the history of ethnography has been rarely discussed until now.

The deer dance mask was often a starting point for conversations about expectations and attitudes towards ethnographic museums broadly.

The dialogue with visitors makes it clear that a polyphonic examination of historical and cultural perspectives can promote not only the understanding and reflection of colonial history by visitors, but also sustainably influences their engagement and openness towards subjects of ethnography.

Johanna Martens is a cultural scientist. She has been working as a guide since 2016 and a Live Speaker at the GRASSI Leipzig Museum of Ethnography since 2019.

In interviews with visitors she examines their reactions and associations to a teepee, shown in the “Völkerfreundschaften” exhibition.

The tepee is displayed together with the topic of ‘hobbyism’ in the ‘Völkerfreundschaften’ exhibition.

As a part of my project, I led conversations with visitors and employees at the exhibition and recorded four of them. They serve insights into the impressions and interpretations of the visitors regarding the topic of ‘hobbyism’.

By reading anti-racist theories or following socio-political debates in the media, many visitors have developed a heightened sensitivity for certain words and practices. We often talked about dressing up as ‚the other‘.

I opened conversations with the question, what visitors thought and felt, seeing the tepee in the exhibition. The conversations open a polyphonic image on the topic of hobbyism and invite to you to develop your own attitudes on the subject.

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The interviews contain the term ‘Indian’. It is often criticised as stereotyping and racist. Many indigenous people in/from the USA and Canada nowadays prefer different labels, such as ‘first nations’ or ‘Native Americans’. We have developed the magazine "Is it okay to say ‘Indian’?" for you at the exhibition, which captures the controversy around the term from different perspectives.

A visitor gives fascinating insights into the lived culture of the indigenous North American people. He compares aspects of the culture of hobbyism in West- and East Germany and reflects on current developments within the scene:

At such large meetings, it should be authentic. I was in America at a powwow. The natives came in cars. There were hardly any tepees, maybe three, four were standing around, but the rest was trailer homes. The powwow is always in a circle. At that size in America, there are five, six drum groups taking turns dancing, drumming and singing.

So that’s what it’s like in America, it’s not as big here. We were at the medicine wheel of the Cheyenne. It is a giant medicine wheel made of rocks. And what a diameter! A diameter of twenty, thirty meters. There the natives prayed and put some things inside.

The hobby is rather small in Germany. And when you go to a meet-up, you meet the same people. […] Then we’re talking shop, for example, how to correctly build a tepee. If someone is struggling, everyone goes “I’ll help, I’ll help!” The young people help without hesitation. And then such a tepee is up standing relatively quickly.

There’s one of our old timers from Berlin. He’s made his own embroidered jacket, which weighs a few kilograms. […] In the GDR we understood the Indians as a people oppressed by the white Americans. The Americans weren’t held in high regard here, but if someone wanted to start up something Indian-related, that was promoted. […] It is way more widespread here than, let’s say, in West Germany.

When we were small, we played Cowboys and Indians. That’s what it was like back then. And then came the Winnetou movies, Pierre Brice, Lex Barker and then there was a boom. And then, after that came the realistic Indian movies, but that was the beginning of the end. Just like now, it became less popular. Now we barely have any new blood in West Germany. […] I am 76 years old now and I still do this, because it’s just nice.

.

.

.

A different visitor reflects on different facets of hobbyism. On the on hand, she describes a universal human need for play and role playing, expressed in the imitation of rites and practices of North American indigenous people. On the other hand, she adds for consideration, hobbyism could help repeat and reinforce stereotypical imaginations:

I myself never played that as a child. I think for us it’s a playful, imaginative thing, what children play. I have a humanist reading. People in Germany, so far away, can see that and somehow want to do it again. Yes, maybe there is this problematic side of it too. But there is this wish. You must reflect a bit, where that wish is coming from. That wish, to return to earth a bit. […] Yes of course, that can create many problems, or stereotypes.

It would be easy to say, that koreaboos (pejorative term for people who fetishise Korean culture - became a buzzword in the wake of the K-pop craze) or people like that want to control this strange culture and I think it’s somehow human. It is a kind of play acting, roleplay. I think it’s impossible to say, all that is somehow problematic, no?

What I see here in these images, this surface-level, romanticized, sentimental and this certain image of this culture, that means, they really do have different reasons. I think it is problematic, somehow, when they use this image for political purposes, but for me, when I see this, I can really see that aspect: Hobbyists. It’s just a hobby. So, my conclusion is people have problems living life and they need all sorts of fantasy and play in order to cope with it.

So, this cowboy thing, to me, that is this reenactment of violence or something, right? Reenactment of a romantic colonizing past. That, to me, is also an outlet for more dangerous feelings. They want something very far removed in time and in culture. The goal is not, to somehow engage with Indians today. It’s the same with Korea, this Koreaboo-thing. It was so far away, so different and strange from your own white, European life. You want something, that is that different. […]

People always need a space for fantasy, I think, life is impossible without.

Filipa Pontes is a visual artist and ethnologist. She has been active as a Live Speaker, guide and workshop leader at the GRASSI Leipzig Museum of Ethnography since 2022.

For the Voices project, I am presenting the artwork „Evocations“, which reflects the diverse imaginations, emotions, and ideas arising from a collaborative approach to a specific item from the collection. How can we share culture with a pluriversal approach?

A museum of ethnology can be seen as a place where cultures and histories meet. In the 21st century, a museum of ethnology aims to be a center for research, knowledge, production and distribution of knowledge. It involves a multiplicity of actors who critically review the collections in relation to the coloniality intrinsic to them.

As James Clifford points out, the museum is a „contact zone“. Different perspectives, narratives, and knowledge enter into conversation and negotiation in contact zones. They also clash, mainly because universalizing Western epistemology imposes itself on other epistemologies, preventing the development of pluriversal knowledge.

In an effort to incorporate other knowledge, perspectives, and the stories that have previously been omitted about the collections and their provenance, the Leipzig Museum of Ethnology proposes to expose these issues not only to visitors, but also to negotiate them with visitors.

The Live Speakers, as mediators, are the point of contact between visitors and the narratives presented in the exhibition. Visitors are invited to share their views, criticisms, and questions. Together, we contemplate the complexity of the collections and the museum's role as a repository of knowledge and envision the future of ethnological museums.

Filipa Pontes: Evocations, 2024

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

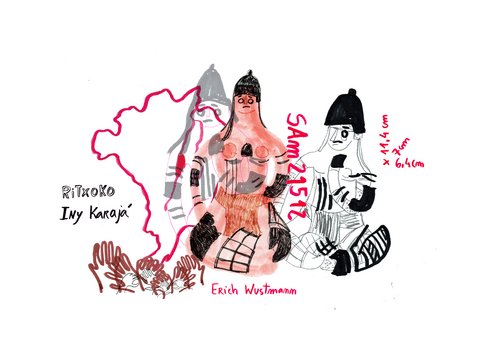

In my approach, a Ritxoko doll belonging to the Iny Karajá people from the central west region of Brazil, collected by GDR ethnologist Erich Wustmann in the 1950s, serves as a central element in initiating dialogue. The mixed-media drawing is created through interactions with visitors and reflects various perspectives, divergent views, specific interests and incomplete answers.

The rudimentary appearance of the drawings signifies, on one hand, the limited access to in-depth knowledge about the Iny Karajá people, indicating an ongoing and necessary research process. On the other hand, I pay homage to aesthetics that, although seemingly simple, convey forms of immeasurable ancestral knowledge transmission.

Concluding Remarks by Uli Reible

In ethnographic museums, questions about German and global colonial history and its consequences are highlighted, which are expressed today in inequalities, discrimination and racism that still exist. Not all visitors are prepared to be confronted with such issues, and sometimes guests feel insecure or uncomfortable as a result. It is important to me to meet these visitors in their individual life situation and to treat them with respect. My aim is to promote an understanding of complex content that is difficult to convey and to enrich the museum visit.

I find it particularly inspiring when visitors have their own suggestions for presentation and communication. For example, one visitor had the idea of staging the collection completely without texts and explanations and having the live speakers contribute all the background information. After all, the act of exhibiting always changes the context of the objects, which were rarely created for a museum.

For me, working as a Live Speaker feels a bit like field research. Both positive and critical feedback can lead to lively dialogue. Although the museum's collection is historical, the themes of the exhibition are current and relevant at all times. The intensive examination of one's own history in relation to cultural and political issues is also an important contribution to an open and tolerant society.

We cannot change the past, but we can decide which stories we tell and how we tell them.

The Live Speaker project is currently on hiatus due to a lack of funding.

Auch Interessant:

In the spring of 2020, a very special troupe of brightly coloured figures took up residence in the depot of the Puppentheatersammlung. Fishers and farmers, musicians and child gymnasts, not to mention ducks, water buffalos, dragons and fairies. They all belong to the classic cast of Vietnamese water puppetry.

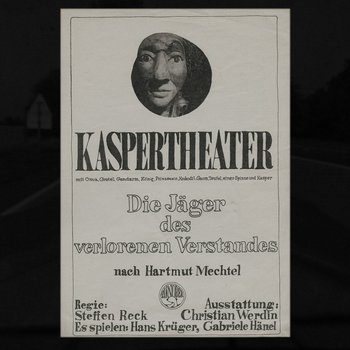

What declares itself to be nonsense declares itself to be harmless. Supposedly. Because the consequence of such self-determination is the famous jester's license, which a group of theater people in the GDR also claimed for themselves in the 1980s when they called themselves “Zinnober” and began making Punch and Judy shows for adults. Their play “Die Jäger des verlorenen Verstandes” (Raiders of the Lost Mind) can easily be read by the audience as a mockery of the GDR state system and its toleration is hard to believe in retrospect - but true.

Precisely one year ago, news about the Capitol riots in Washington, D.C. went viral around the globe. Among videos and images of thousands of Trump followers, conspiracy disciples, right-wing militias and Alt-Right activists, large numbers of people in flamboyant costumes dominated the media, most of all Jake Angeli, a.k.a. the “Q-Shaman,” armed with a horned fur headdress and a US flag tied to a spear. Frank Usbeck already addressed this mishmash of cultural and historical references in a SKD blog contribution back in the day – we’re republishing his blog post today.

![[Translate to English:] Plains Cultures Feather Bonnet with Horns](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/6/csm_Img01_Federhaube_19275e1a40.jpeg)