ostZONE came about in cooperation with the Dresden association Kultur Aktiv e.V. and will be continued in the Albertinum on 17 August 2024.

I came to the GDR in 1979 at the age of 16 and today live in Dresden. After taking a language course in Brandenburg, I started vocational training as a plant fitter in Weimar and gained a qualification as a skilled worker. In 1987 I moved to Freital, where I worked as a translator and interpreter and took care of the Vietnamese women who worked at the state-owned enterprise manufacturing children’s outerwear in Freital. I initially only translated and interpreted, but later went on to carry out other tasks that were not in my contract, such as instructing them on industrial safety and the rules in their housing unit.

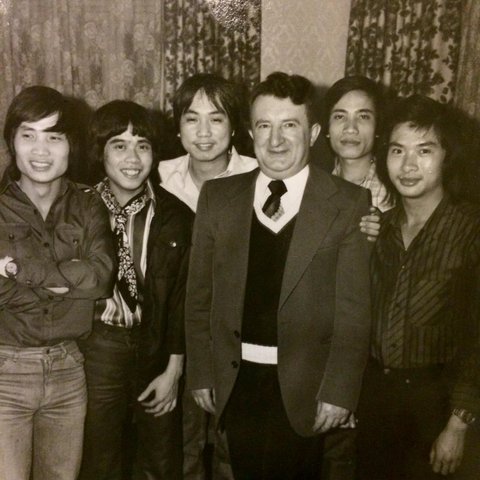

Workshop mit Zeitzeug*innen “Jeans nach Dienstschluss” mit Hung Cao The und Van Ngoc Pham

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Iona Dutz

My workshop in the “ostZONE” project was called “Jeans nach Dienstschluss” (Jeans After Hours) because we started sewing after work. I told the workshop participants how we produced tailor-made jeans in the housing units during the 1980s. We taught one another how to sew. Visitors came to the housing unit, we took their measurements and got sewing. One key question was “What brand do you want? Wrangler, Montana, Levis or Lee?” But everyone just wanted Levis rivets and labels. We ordered the labels from other foreign contract workers in Poland; copies were already around in Poland back then, too. We charged 120 marks for one pair of jeans.

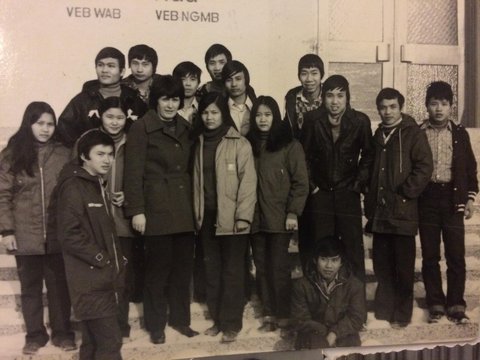

Aufgenommen in Neubrandenburg: Deutschkurs mit Lehrerin

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

We too dreamed of Western goods; real or fake, we didn’t care. With the right connections, we could exchange the money we earned and buy T-shirts at Intershop, which sold products from the West: Boney M. and ABBA – we always dressed cool. Contract work didn’t pay well; sewing ten pairs of jeans a week earned me a month’s pay. We worked day and night; why not? Schwarzarbeit means moonlighting: working “black”, by night. I call our sewing Rotarbeit, working “red”, as no-one stopped us. The GDR itself could not produce enough to meet requirements, so it was simply ignored. We even supplied the police. Demonstrating and travelling to the West were prohibited, but not Rotarbeit.

Thieves kept breaking into the housing units. I think it was racism, but covert racism; not as overt as later. I think they were jealous of the units’ facilities and the bikes and mopeds we had. We bought a lot to send to Vietnam; it was our duty to provide support, as Vietnam was cut off by the war and conflicts. After German reunification, I was laid off, and there was little demand for the jeans any more. It was then that I moved to Dresden. We were offered 3000 DM in compensation: “Take this 3000 DM and go home”, we were told. 90% went back to Vietnam. Many didn’t want to stay, partly for fear of racism, and decided to leave of their own free will. Others saw the 3000 DM as start-up capital in Vietnam.

Berufsausbildung in Weimar: Wohnheim mit Lehrmeister

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

I was already integrated here and wanted to stay. But my job qualifications were not recognised, and the jobs were mainly for Germans and European guest workers. That’s why many of us decided to start our own businesses. I worked with textiles again, selling mixed goods as a travelling salesperson at markets, as retail space was expensive. Later I worked for an alterations service. I also did nail design. That’s an art – it’s a work of art. Being able to keep myself entertained helped me do that job, but I found it hard to sit for so long; I'd rather be active.

I’ve been working for the Vietnamese association for almost 20 years now, mainly organising cultural events. I’ve been at Afropa e. V. for 5 years. It’s a good job for me. I have a rehearsal space here for my band “Dresdner Brüder”, and I’ve worked on a lot of projects in my time here: seminars, exhibitions, music festivals – anything about Vietnamese culture. Many Vietnamese people here take up painting or drawing as a hobby, so I have set up a gallery for them here at the club. The space is like a playground for our children; they can exhibit pictures here. A museum is more about the older generation; here at the club we display works by the younger, third generation. But it isn’t easy to get works from everyone, or to get money for the projects. Money is always hard to come by, and I do a lot alone.

Workshop mit Zeitzeug*innen “Jeans nach Dienstschluss” mit Hung Cao The und Van Ngoc Pham

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Iona Dutz

My other projects are about Vietnamese art, cooking and emigration. The city tour I led for the “ostZONE” project is kind of connected to that, too. It’s an opportunity to get to know our restaurants. During the walking tour on Alaunstraße, I presented more than ten of them belonging to our community. Today, Vietnamese cuisine plays a major role in Germany and is integrated. You have to eat every day, and Vietnamese cooking is very healthy. I know a lot of people who run restaurants on Alaunstraße, and we are currently trying to get it called “Hanoi Straße” for tourists: we want to give the street a name related to us.

Stadtspaziergang “Die Neustadt zwischen Hanoi und Havanna” mit Hung Cao The, Bui Truong Binh und Dr. Hussein Jinah

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Nora Börding

Vietnamese culture is important to me; we are part of the German populace too, but we should also remember the things we brought with us: the food, art, clothing and language. We are a German minority, and Germany is a country with a lot of cultural groups. A diverse country is a country where people feel at ease. It’s not like it used to be. We’re not just Vietnamese; we’re also German. We want to share our festivals, and our events are for everyone. We brought the festivals with us and they, too, are part of Germany. Our children are German; it’s only us who come from Vietnam.

Stadtspaziergang “Die Neustadt zwischen Hanoi und Havanna” mit Hung Cao The, Bui Truong Binh und Dr. Hussein Jinah

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Nora Börding

I’ll soon be travelling with Dr Verena Böll to Vietnam, where we'll be talking to return migrants. We want to get in touch and collect their stories: When we meet again in old age, how successful or unsuccessful will we be? We’ll be visiting former contract workers, and artists who worked and studied in Germany back in the day. They are all more than 80 years old. Many others have already died. The art students were influenced by the GDR and are now famous artists in Vietnam.

Huy Van Le is one example. He studied in Halle and is the director of an art college in Hanoi. We know each other well, and he lets me use his works of graphic art for my events. Le Huy Van came to Moritzburg very early on, as one of the first Vietnamese arrivals. In the GDR, he studied under Hannes H. Wagner, also posing for him as a portrait subject. This picture shows Le Huy in the foreground, with a hammer. In the background is the Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc, who set himself on fire during the 1963 protests in south Vietnam. The picture is about solidarity. We wonder where this picture is, as it is valuable.

Solidarity was a reference point for me, too, in the exhibition. There were lots of solidarity-themed postage stamps that were about Vietnam. A lot of the material in my collection, too, features symbols of solidarity with Vietnam. Solidarity actually used to mean helping one another. During Covid, we sewed 20,000 masks within a very short time in the community, for hospitals, care homes and doctors. We also imported a lot from Vietnam. We are Dresdeners and have to do something for the city when help is needed.

Workshop mit Zeitzeug*innen “Jeans nach Dienstschluss” mit Hung Cao The und Van Ngoc Pham

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Iona Dutz

In the exhibition, I found it particularly interesting to see how different countries showed solidarity. It would have been good if they had done more work with Vietnamese people, as there’s little sign of our story apart from a few pictures by Vietnamese artists, and a few photos. There’s a lack of collaboration. More works are needed by Vietnamese artists, and pictures of our history. We’ve also got photos, memories and items in our private archives. During the art talks, I presented the exhibition to our community and other visitors. Many of us make art, and we too want to make a contribution in Dresden as a city of art and culture. There should really be an exhibition like this every year.

At one event, I told you: “It’s nice of you to invite me, but also a bit late.” After all, the people who witnessed our history are still alive, but some are very old; some almost 100 years old. I have lots of photo albums and poems compiled by the first generation; the first Vietnamese people in Moritzburg. They have a lot of material they want to give me, and I’ll be left their archives when they die. But those who are still alive need to be involved now, and asked questions.

Workshop mit Zeitzeug*innen “Jeans nach Dienstschluss” mit Hung Cao The und Van Ngoc Pham

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Iona Dutz

I organise these talks for museums with witnesses to history, and art talks, as I want to use my time to tell young people who did not live through the past about what happened. I want to tell the general public that this perspective is part of it. We live in a country of freedom and democracy, and it must be interesting for the second and third generation to hear about our experiences. There are also a lot of stories that have not yet been heard, which is why I am always ready to talk about them when opportunities like this arise. German citizens know about some aspects of the past in the GDR, but we contract workers had a different experience working for enterprises and living in housing units. There should really be an exhibition about the history of Vietnamese women at some point.

Keep Reading:

With the “Ortsgespräche” series, the Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann is making itself available for art locations in the so-called rural areas of Saxony, where the diversity and social relevance of contemporary art is sometimes discussed with particular vehemence. The Hoffmann Collection has cooperated with the rural village Prösitz and the female artists working on the Künstlergut (artist's estate) Prösitz, where they produced thought-provoking art concerned with the A14 freeway that dominates the local resident's day-to-day lives.

![KilligBild [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/8/csm_040624killig001_e048c2ccda.jpg)

On 13 October 2022, the Albertinum of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden hosted the conference “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-)Communist Europe.” A report by Julia Tatiana Bailey and Christopher Williams-Wynn.

For the “Counterpoints” project, the SKD are studying the international history of the East German cultural sector - a project about the history of their own collection; about dialogue and networking. Above all, however, it is about correcting the narrative describing that history as provincial and isolated from modernism. In June, TU Dresden’s Chair of Visual Culture Studies in a Global Context organised a conference on the ties between the GDR cultural sector and the Global South, working with the Albertinum and the TU Office for Academic Heritage, Scientific and Art Collections.