Man must have dominion over nature and that nature is merely a playground for his activities.

Stappmanns, Viviane/ Kries, Mateo/ Vitra Design Museum und Wüstenrot Stiftung (Hrsg.):

Garden futures: designing with nature, Weil am Rhein: 2023, 16.

Nicolas Lancret: Tanzbelustigung im Schlosspark, um 1725

© Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The concept of nature as a playground and plaything for humans has been an established notion for many centuries in the western world. However, it is now increasingly being questioned, criticised and challenged. If we take a closer look at the connection between nature and play, some links are apparent and reveal the tension between nature and artifice on one hand, and control and loss of control on the other. Starting from the creation of pleasure gardens, with their amusement park-like character, I attempt to draw a parallel to present-day golf course culture, taking Schlosspark Pillnitz as an example. Its political and economic systems have always been closely linked to grass as the dominant cultivated plant.

This raises the question of the extent to which our control of nature and gardens has always been tied to entertainment. Which power constellations, associated institutions and beliefs are behind the creation and shaping of nature and the corresponding social games and rules? Which systems, instruments and infrastructures are set in motion to keep the game moving? Can using games as a lens through which to examine our shaping of nature help understand human exceptionalism vis-à-vis nature, in order to subsequently deconstruct it with this knowledge?

While interrogating these aspects, we present Plant Circus, a film project combining documentary and artistic approaches produced in the context of the Curating Change workshop at Design Campus 2023. The work ironically poses the question of whether it is not in fact humans who have actually become pawns in their own garden design.

Who plays in the pleasure garden?

The pleasure garden has always been associated with entertainment, enjoyment, relaxation and refuge from societal conventions and, above all, play.1 Originally private, later public places, these beaux jardins developed in the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe, primarily in England. Besides their standard function as places of relaxation, the wide-ranging attractions like opulent concert halls, zoological menageries, colourful carousels and fireworks were the gardens’ main characteristics. Pleasure gardens can therefore be seen as the first form of leisure park.2

1 Wimmer, Clemens Alexander: Geschichte der Gartentheorie. Darmstadt: 1989, 414.

2 Philips, Deborah: Fairground Attractions: A Genealogy of the Pleasure Ground. 1. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2012, 9.[Link][29.09.2023]

3 Fröhlich-Schauseil, Anke: Barocke Spiele im Schlosspark von Pillnitz ein Ort des Feierns und Spielens, in: Die Gartenkunst, Worms: 1/2016, S.33-46, 42.

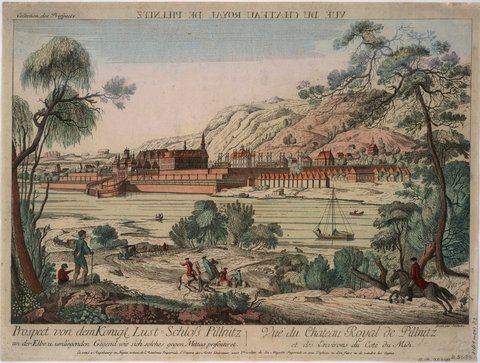

Johann Christian Nabhol(t)z nach Johann Alexander Thiele: Prospect von dem Königl. Lust=Schloß Pillnitz / an der Elbe u. umliegenden Gegend wie sich solches gegen Mittag presentiret, undatiert

© SLUB Dresden, Kartensammlung

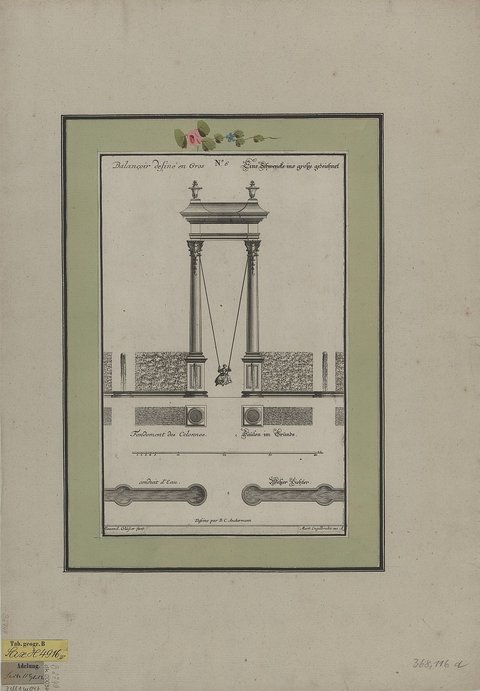

A design feature of the garden that remains particularly striking today are the aforementioned charmilles, which were created in 1713, and also have their roots in games. This 3.50 m high hedge-walled playroom was planted for the established bowls game. One each of the six areas was intended for a version of bowls – at a time when there were “almost one hundred common forms”4 of this courtly game. Cutting the hedges to the required height and thickness was a challenge at the time, and remains so today, for the gardeners who maintain the plants’ growth in constant rectangles with patience and expertise. The 20 swings, each five metres in height, that were located outside the entrances to the hedges, are no longer present. Compared with swings as we know them today on public playgrounds for children, the baroque versions seem all the more opulent.

4 Fröhlich-Schauseil, 41.

B.C. Anckermann, Stecher A. Gläßer, M. Engelbrecht: Grund- und Aufriß des Kgl. Poln. und Churfürstl. Sächs. Lust-Schloß Pillnitz genandt, an der Elbe eine Meile von Dresden - No. 6 Eine Schwencke ins große gezeichnet, um 1730

© SLUB Dresden, Kartensammlung

The activities in the garden allowed visitors to escape their roles at court at least for a short time. They either indulged in the dizzy feeling of swinging, or dressed up as farmers, temporarily relinquishing their court status and perhaps using another pretence for more physical proximity. While this form of courtly play was a form of entertainment, it can also be viewed as a strategy of the ruling class. Within the confines of a specifically limited framework, certain liberties could be taken, such as playful tests of strength or physical training. In his book on cultural theory, “Homo Ludens”, Huizinga defines play as an act:

Peter Paul Rubens / Peeter Clouwet (Stecher): Der Liebesgarten, 1650-1670

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

that is perceived as outside the bounds of normal life, (...) that occurs within a specifically determined period and space, follows specific rules and creates a feeling of community, which in turn is often shrouded in secrecy or distinguished from the normal world via a disguise.

Huizinga, Johan: Homo ludens: vom Ursprung der Kultur im Spiel, Reinbek bei Hamburg: 2022, 22.

The pleasure garden, with its primly pruned, orderly and manicured plants, is a perfect backdrop – an artificial playing field of its day. It is the place and time where people can play. In this cosmos, the members of the courtly society become pawns in a game. Accordingly, not only the plants but also the visitors to the palace garden were subject to the aristocratic ruler’s will-to-form. They all played a part in an artificial total work of art.5 Accordingly, art historian Anke Fröhlich-Schauseil notes in her analysis of the pleasure garden in Pillnitz:

5 Wimmer, 424.

In choreographed processions, horse ballets, races or balls, tilting at rings or balls, the crowds with horses and props could be seen as moving patterns or ornaments in space. In this, they resemble the unmoving patterns of vines, ornaments, bosquets and the decorations on the walls, furniture, clothes etc. [...] It can be assumed that this perspective, i.e. a perspective as symbolic form, focuses specifically on the person, on the eye of the ruler: he looked upon the state whose order was reflected in the staged order of his subjects.

Fröhlich-Schauseil, 35.

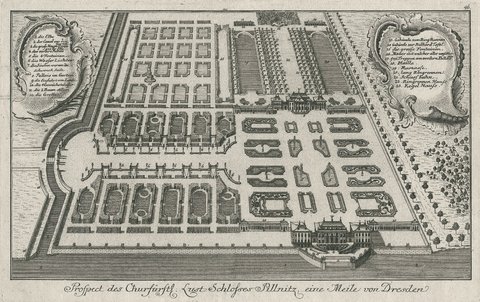

B. C. Ackermann, A. Gläßer, M. Engelbrecht: N°. 12. Der Haupt=Plan vom Pillnitzer Garten und Schloß an der Elbe gelegen. [...] 23. Ballon u. Longuebó, um 1730

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The Schlosspark – once dedicated to pleasure of another kind – is still accessible to garden fans. Preserving garden art from bygone days may be nothing more than holding on to the past in an age when nature is increasingly being destroyed.6 The aristocratic playing field can still be visited. However, there are new rules and instructions in place to preserve the historic monument: “Please do not sit on the branches” or “Please do not walk on the grass.” Visitors follow prescribed paths and sit on the park benches provided.

6 Wimmer, 431.

Against the backdrop of this scenery, the short film Plant Circus by Mludek, Schwarz und Sulikowska portrays a typical day at Pillnitz park and palace, and the perennial, apparently absurd, performative acts of the gardeners. The lawns are mowed, the edges are straightened, weeds are burned and, just as in 1713, the hedges are cut to a height of exactly 3.5 metres. The video raises the question of who has been performing for whom all these years? The plants for the visitors? Or the gardeners for the plants? If we transpose this concept to lawns, are we merely the pawns in a game of our own design?

The social game of lawn care

Lawn articulate the ideologies of those who create […] them

Kozlowski Moore, Kris: On the Lawn. In: Garden futures: designing with nature, Weil am Rhein: 2023, 92

Lawns as the ground, or rather the background for play, seem just as natural to us today as the cultivated plant itself in our everyday lives. This development can also be construed as an extension of the balance of power and demonstration. Lawns have been integral from the start as a quasi-natural element, beginning with English landscape gardens, above all as a symbol of excess in the shape of an uncultivated space. This perspective remains true today. “And so, there is a large green space outside the German Bundestag, and when the American President has something important to announce, he does so on the lawn outside the White House.”7 Green grass grew in popularity among the US middle class after the invention of the lawnmower (Edwin Budding 1830) and the creation of American planned cities and front garden culture, like Riverside and Levittown at the end of the 19th and early 20th century.8

7 Pöhner, Ralph: Die große Güte Verschwendung, Tages-Anzeiger 2017, [Link][29.09.2023].

8 Kozlowski Moore, 96.

9 Jenkins, Virginia Scott: The lawn: a history of an American obsession. Washington, D.C: 1994, 72.

Today, as Kozlowski Morre writes in his article, there are over 40 million hectares of irrigated lawns in America alone. One third of all household water consumption is used for lawn irrigation, 27 million kilos of pesticides are consumed and approximately 40 billion dollars are spent on lawns annually.10 The lawn mafia and industry in Winnipeg played a key role in ensuring that caring for front lawns is enshrined in law. Youtubers like SB Mowing film themselves trimming neglected front gardens and are watched by millions. The video titles often refer to “wild” nature that needs to be tamed: “This home was TAKEN OVER by mother nature – I FIXED THAT” (SB Moving 2023). These videos, perhaps made with good intentions, can still give the impression of individual loss of control, simply because the front garden does not meet the standards expected by society.

10 Kozlowski Moore, 96.

In recognised degree courses, greenkeepers learn the techniques and tools required to preserve the eternal green around the world. They have a whole world of products at their disposal – lawn augurs, special lawnmowers, lawn levellers, lawn edgers, lawn rollers, right up to topdressing sand.

The desire for lush greens now seems to have taken on absurd dimensions given the increasing scarcity of water and the decline in biodiversity, as evidenced by the existence of the professional lawn painters, who spray brown lawns green. The artificial and rolled turf industry is growing steadily, and the products are used in more and more stadiums. Lawns are still the established medium associated with sport and games, and part of the macrosocial game that preserves historically developed power structures.

For thousands of years humans played on almost every conceivable kind of ground, from ice to desert. Yet in the last two centuries, the really important games – such as football and tennis – are played on lawns. Provided, of course, you have money.

Harari, Yuval N.: Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow New York, NY: 2017, 66.

In “Homo Deus”, the historian Yuval Harari writes, as part of a history of lawns, that there is a cultural burden that must be shaken off. Lawns represent something obsolete: something that we doubtless no longer need – a relic of the past, from which we must free ourselves to move on to the future with a feeling of openness, and also to break down historical power structures. In the anthropogenic age, it appears more important than ever before to overcome the ideology of the lawn. It remains to be seen what the game and the playing field of the future will be and who will design them. What will the pleasure garden and the golf course of tomorrow look like?

Also of interest:

This year, the Design Campus at the Kunstgewerbemuseum is all about plants. In their opening lecture for the Design School, design duo d-o-t-s, who also curated the exhibition Plant Fever, call for a rethinking of the relationship between humans and plants. d-o-t-s on the invention of the salt shaker and rooting robots.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/2/csm_230721_Becoming_Plant_OCo_Inauguration_Lecture_Slides_page-0012_1769982be8.jpg)

At the beginning of every project, there is always a trigger, a motive. It can be an intuition, a book, or an article… What sparked the idea of Plant Fever, was a conversation that Laura Drouet had with the Italian design duo Dossofiorito. Learning about their plant-conscious practice, one question arose: were there other creatives looking at the vegetal realm with respect and curiosity, using design as a means to establish senseful relationships with plants the way in which Dossofiorito were doing? ? Could this be the subject of an exhibition?

If you happened to sit under the hop-draped pergola in the garden of the Japanisches Palais in May or June, you may well have been surprised by how sticky the leaves were. If you looked more closely, you will have spotted hundreds of minute black insects clinging to the plant stems or the undersides of the leaves: aphids.