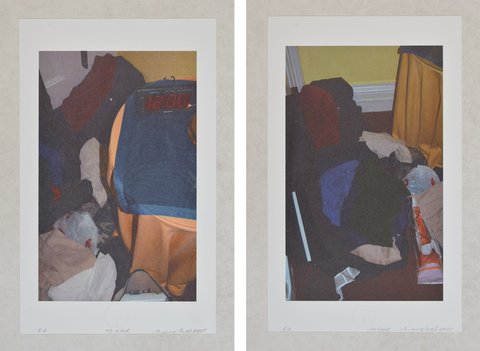

Eberhard Havekost: "12 Uhr" und "14 Uhr" (2005)

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Foto: Werner Lieberknecht

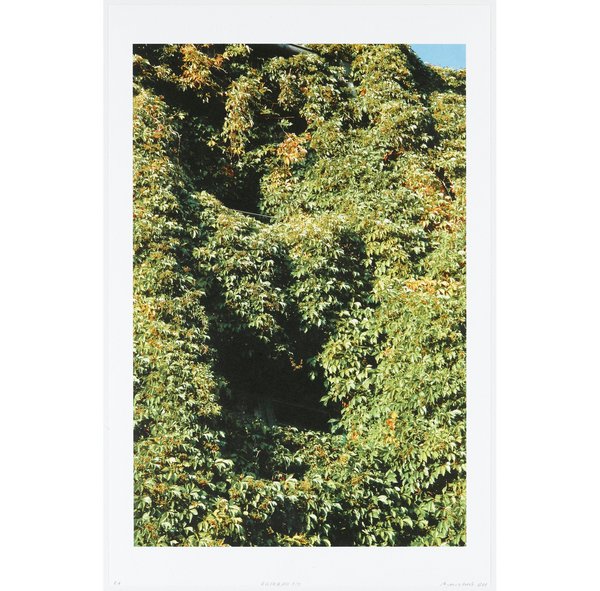

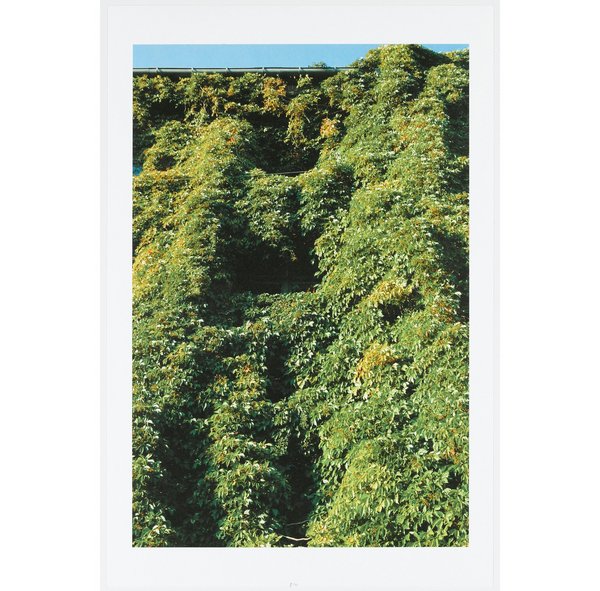

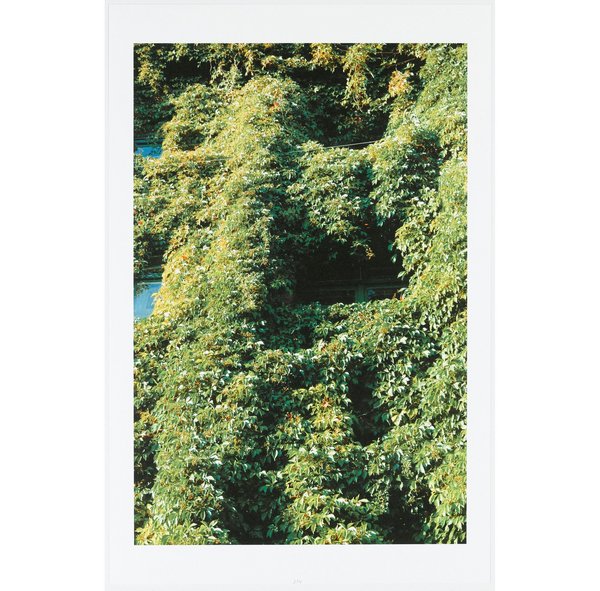

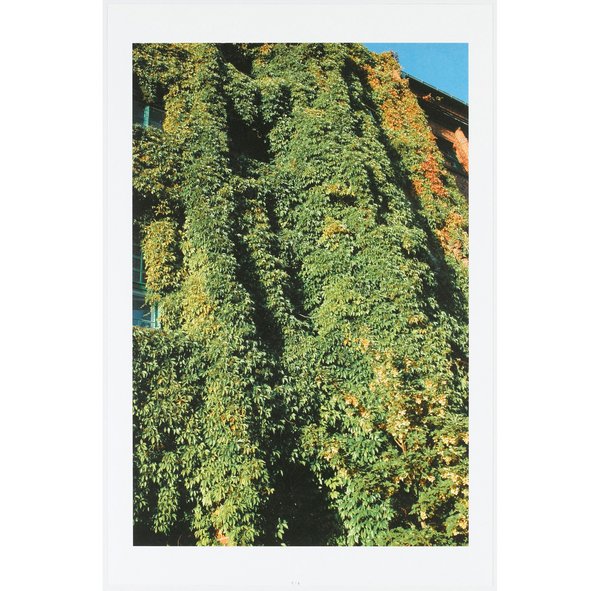

In his work titled 12 Uhr, Eberhard Havekost captured a non-descript room. The floor is cluttered with bags and a digital clock – signaling 12:00 – is set on a table. The cropped frame and unusual angle make it hard to discern the overall lay-out of the space; we are enclosed, so to speak, by boundaries. At first glance, it is easy to imagine that the digital clock represents the literal passing of time measured by hours and minutes. Havekost seems to capture a sense of melancholy of a moment just missed, in the atmospheric sense of pastness. The artist took another shot of what seems to be the same admitedly dull room, showing the same heap of bags, but from a slightly different angle so as to suggest a different perspective on the same. Titled 14 Uhr, he made sure to tell us that this shot encapsulates a different moment in time. But as he returned to the same spot (two hours later, or perhaps a week, a month?), nothing seems to have happened. The bags are still on the floor. Are we faced with dreadful monotomy, lulled by an impression that the works are simply repetitions of the same, or should we keep our minds open?

Looking at the two prints (which are based on digitally processed photographs) made by Havekost in 2005, a concept from a particular text of the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard – his book Repetition from 1843 – comes to mind. In the guise of Constantine Constantius, Kierkegaard attempts to relive a love affair that was lost from the start. His search for repetition is compulsive – it drives him to keep going back, looking to retrieve something. He goes to the same theatre in Berlin to see the same performace, sits in the same seat, admires the same actors, listens to the same jokes, etc. But nothing goes as planned: he tries to re-enact his past experience only to discover that he can go back to the same location and re-enact the material conditions, but he cannot return to his former perceptions and feelings. So Constantius (Kierkegaard’s alter-author) writes, “I became bitter, so tired of repetition that I decided to return home. I made no great discovery, yet it was strange, because I had discovered that there was no such thing as repetition. I became aware of this by having it repeated in every possible way.”1

How do Kierkegaard’s musings on the impossibility of repetition relate to Havekost’s images of a room somewhere at 12 and 14 o’clock? The compulsive structure of repetition is also found in Havekost: One of the chief concerns throughout his career was the repetition of a few motifs – faces, facades of blocks of houses, caravans – that surround us in everyday life. In many of his works, he plays with variations of the same motifs from different angles or crops different sections from the same shot. A reliance on repetition is a common artistic strategy. It may lead to new angles, new arrangements, new ways of being affected by the same. This is also true of 12 Uhr and 14 Uhr; but here repetiton is not merely formal but a temporal category.

For Kierkegaard-Constantius, in all his efforts to repeat something, the only thing that repeated itself was that no repetition was possible; he was left with his unsatisfied desire for return. His repeated acts of going back marked both the impossiblity of return as well as the many possibilities of perception and feeling remaining. To repeat is to allow for new feelings, new variations to come into being. Kierkegaard keeps going back, but the experience is different each time, the now is ever new. Havekost, too, does not seem to have believed in repetition, even as he returned to the same motifs over and over again. In an interview with Sven Drühl in 2004, he says, „this is the only way I can see what has changed in my perception of things.”2 Repetition, one might say, precisely changes meaning over time.

12 Uhr and 14 Uhr offer to two perspectives, but we hardly see any change, just the same scene at different times from slighly different angles. Time almost feels like a burden, as nothing has happened. Isn’t this precisely a case of repetition, one that awakens a desire for change, for something new? Looking at Havekost’s images, I wish to escape the everlasting sameness. Does Havekost show us that, contrary to Kierkegaard, repetition is possible after all and unheimlich as well? Or is Kierkegaard right, because in their repetitiveness, 12 Uhr and 14 Uhr give us a new perspective on time: the two hours in between have to be filled with meaning by us.

1 Søren Kierkegaard: Die Wiederholung. Die Krise und eine Krise im Leben einer Schauspielerin, Übersetzung Liselotte Richter, Hamburg 1991, 42.

2 Eberhard Havekost: „Intime Momente, aber auch Landschaften, Hausansichten, Müllhalden, Innenräume, Menschen aus Zeitschriften und Magazinen, Stars, Segelflugzeuge, Wohnwagen“. Ein Gespräch mit Sven Drühl, Kunstforum International 170 (2004), S. 218–227, hier S. 227.

This text is part of the exhibition “Feeling time. Experiences of temporality” (9.12.2022-27.2.2023), curated by Jane Boddy and Michael Griff.

Auch interessant:

Feeling time: How do we experience time? Punching a time-clock every hour for one year is an intense task, to say the least. Evelyn Wan elaborates on the relevance of Tehching Hsieh’s seminal work “One Year Performance” and considers how it resembles our current environments of labor.

In many ways, Tom Hunter’s “Woman reading a Possession Order” seems to capture the effect of Vermeer’s original painting “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window”. Yet if one looks more closely at Hunter’s photograph from 1997, differences become apparent. Jane Boddy on an iconic image and its contemporary appropriations.

![[Translate to English:] Tom Hunter, Woman reading a Possession Order, 1997.](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/c/csm_Abb3_Tom_Hunter_Woman_Reading_a_possession_order_e8db018977.jpg)

Marijke van Warmerdam’s work Eiskugel – quite literally an ice ball of ∅ 25 cm – is a modest piece that might have been somewhat simple if it weren’t also slowly melting in the gallery space. Jane Boddy on the tremendous energy put into the production of a clear, carved piece of ice currently on show at the Children’s Biennale "Embracing Nature" at the Japanisches Palais.

![[Translate to English:] Marijke van Warmerdam, Eiskugel, 1998. Photo: SKD, Oliver Killig.](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/5/csm_290321killig030_6a0648dbb8.jpg)