On 13 October 2022, the Albertinum of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden hosted the conference “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-)Communist Europe.” Organized by Kathleen Reinhardt (Curator of Contemporary Art, Albertinum) and Julia Tatiana Bailey (former Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, National Gallery Prague), the conference brought together early and mid-career scholars to present and debate revisionist accounts of Cold War artistic exchange. At its core, the conference sought to further disrupt narratives of East–West “defection,” in order to provide a far more complex understanding of cultural contact, exchange, and interaction during the Cold War. Although a second aim of the project was to explore how and why artists from the “West” entered the “East,” the presentations and discussions revealed a far wider range of meeting points, connections, and disjunctures.

This conference was presented in conversation with the research and exhibition project Revolutionary Romances: Transcultural Art Histories in the GDR at the Albertinum. This large-scale project focuses on cultural relationships from 1949 to 1990 between the German Democratic Republic, socialist-oriented countries in the Global South, and independence movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, previously resulting in the conference “The Global GDR – A Transcultural History of Art (1949–1990).” The conference “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold” was made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art and built on the Art in Translation/University of Edinburgh anthology project Hot Art, Cold War.

In keeping with the goal of unfolding various new narratives for culture during the Cold War, the day was organized around three thematic sessions. Border Crossings focused on innovative channels for the cross-border circulation of art across Cold War divides, spanning Europe, North Africa, and Latin America. Middle Grounds addressed the spaces that provided platforms for artistic collaboration based on shared values between artists on opposing sides of the Iron Curtain. Other Meeting Points highlighted how racialized artists in the United States explored the potential of socialist artistic practices in Eastern Europe to inform their quest for rights and recognition at home. Each session was followed by a Q&A open to in-person and online attendees. To ensure a close dialogue between art historians and art creators, the day also featured interventions by internationally renowned artists with research-based practices on these topics: Jasmina Cibic, Yevgeniy Fiks, and Slavs and Tatars.

Introduced by Kathleen Reinhardt, the first session of the day comprised four presentations that explored innovative strategies of artistic production and transnational circulation between Communist Europe and the wider noncommunist world. The speakers showed how key artists challenged social and aesthetic constraints in the 1950s to 1970s to forge cross-border connections and collaborative practices that encouraged solidarity across Cold War divides.

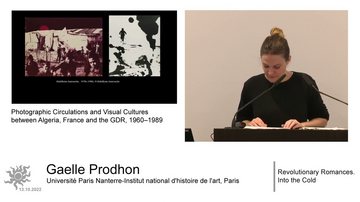

Gaelle Prodhon (University of Paris Nanterre-Institut national d’histoire de

l’art, Paris) began by exploring photographic strategies responding to the Algerian Revolution and its aftermath, as the newly independent country asserted its political autonomy by adapting socialist models. Triangulating Algeria, France, and the GDR in the 1950s and 1960s, Prodhon drew attention to the production, circulation, and manipulation of photographic imagery on all sides, to show how photography as a collective practice became a political instrument at the service of the revolution and post-revolutionary ambitions. In particular, she stressed the porousness of the lines between official, individual, and dissident photography, as photographers operated in complex spaces of visibility.

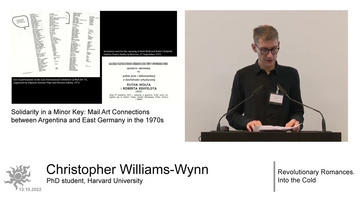

Christopher Williams-Wynn (Harvard University) then sketched what he termed “a minor form of solidarity” that was developed and sustained by the international Mail Art network of the 1970s. By addressing points of intersection, both physical and thematic, between the works of Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt and Horacio Zabala, Williams-Wynn resists the art historical drive to localize narratives by exploring encounters reaching between Eastern Europe and South America. Evoking the recurrent motif of the cage in both artists’ work, Williams-Wynn conceived of mail art as a means for breaking free from ongoing geopolitical and aesthetic structures of production and circulation. This presentation of innovative forms of connectivity at a distance also reconceived familiar methods of contextualization, challenging us to review our own patterns of attention.

Presenting initial archival findings from Poland and Bulgaria, Jérôme Bazin (Université Paris-Est Créteil) introduced a new research project by means of a “double portrait” of two artists whose work exemplifies the ambiguities raised by instances of transnational exchange. Through the example of Mexican painter Olga Costa, whose Russian-German origins were overlooked during her participation in an exhibition of Mexican art in European Europe in the mid-1950s, and the Mexican-inspired mural paintings by Bulgarian artist Yoan Leviev, created in Plovdiv in the late 1960s, Bazin uncovered destabilizing instances of presence and absence, proximities and distances, to explore issues such as incomplete imitations, discontinuous reinventions, and discrepancies of stylization depending on historical and present localities.

Mary Ikoniadou (Leeds School of Arts) concluded the session with a focus on the 1960s’ antifascist graphic designs by Nikos Manoussis for the illustrated magazine Pyrsos/Πυρσός (The Torch) – produced in the GDR under the editorial control of the exiled Greek Communist Party. Ikoniadou discussed how Manoussis’s transnational position as a refugee from the Greek Civil War who trained at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts was reflected in an artistic practice that incorporated references to Greek traditions, German Expressionism, Weimar-era processes, Socialist Realist tropes, and international modernist principles. Ikoniadou showed how Manoussis balanced his “Brechtian” aesthetics with this commitment to Leftist solidarity and the GDR’s aesthetic policies of the time, raising important questions of independence and control. Ikoniadou argued that, in contrast to fine art, the artist’s work in printmaking and publishing – labor considered more aligned with the working classes – enabled its oscillation across and beyond aesthetic and cultural-political borders.

The London-based Slovenian performance, installation, and film artist Jasmina Cibic presented examples of her work developed out of her extensive archival research into socialist histories of modernity. Drawing on documents and photographs in sources that stretched from the United Nations in Geneva to state collections, she explored the myriad dimensions of the former Yugoslavia. Through reflections on her personal artistic practice, Cibic raised questions about the role of modernism as a political tool, both in the historical Eastern Bloc and through its ongoing recoveries and reinterpretations. Cibic’s talk was followed by a screening of her 2015 film Tear Down and Rebuild, which weaves together words taken from historical figures to uncover the paradox of national and ideological representation through architectural forms.

Introduced and chaired by Julia Tatiana Bailey, the first session of the afternoon brought together three scholars and curators to explore the institutions and organizations that provided platforms for creative collaboration based on shared values between artists on opposing sides of the Iron Curtain.

Focusing on Intergrafik 65, an exhibition of graphic art in East Berlin, Sophie Thorak (Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg) demonstrated the extent of lively, international debate coursing through the East German art world. The exhibition, Thorak noted, took place during a period in which the GDR sought greater international recognition and legitimacy, principally by declaring an anti-imperial and anti-militarist stance. Diving into transcripts held in state archives, Thorak highlighted the range of critical perspectives on the aims and means of artistic production with supposedly socialist characteristics. Perhaps most importantly, her paper showed the extent to which singular narratives of art and politics do not hold, even with respect to individuals. Attention to the ambiguities of language too was revealing. Artists and critics called for “Kunst die verändert” (“art that changes”), a declaration that could dangerously refer as much to art itself as the wider social system.

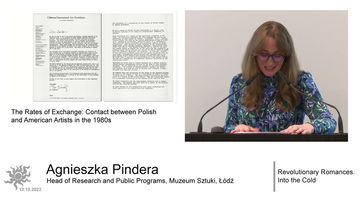

Agnieszka Pindera (Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź) shifted our attention towards a series of encounters between artists from Poland and the United States during the 1980s. As part of a wider revision of Cold War narratives of division, her paper showed the crucial, mediating role that institutions played. Returning to unlikely meetings between the artist Sam Francis, and curators and museum directors Pontus Hultén and Suzanne Pagé, Pindera revealed how they were instrumental in bringing together Polish and American artists at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. She deftly avoided a simplistic story of smooth exchange by also attending to the resuscitation of earlier moments of modernism, such as Władysław Strzemiński’s Neoplastic Room that was designed in 1948, later destroyed, and finally reinstalled at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in 1960. Taken together, these episodes provided a story of international modernism punctuated by delays and discontinuities, recoveries and reinventions.

In the final talk for this session, Maria Anna Rogucka (Jagiellonian University – Humboldt University) reflected on how the political changes in Poland in the 1970s challenge our expectations of East–West cultural exchange. Using the example of the 1979 exhibition at the Studio Gallery in Warsaw of US artist of Polish heritage, Steve Poleskie – part of a wider initiative to cultivate engagement between Polish-American and Polish artists – Rogucka drew a correlation between Poleskie’s distinctive sky art practice – blending drawing, screenprinting, collage, and three-dimensional aerial performance – and his crossing of cultural and geopolitical boundaries.

Closing out the second session, the Moscow-born and New York-based conceptual artist Yevgeniy Fiks appeared in conversation with art historian and curator Ksenia Nouril (The Art Students League of New York). Reflecting on his position as an expatriate artist, Fiks spoke with Nouril about his own use of archival materials to challenge our understanding of Communist histories and their unexpected legacies in the United States.

Introduced by Jérôme Bazin, the final session of the day featured two longer presentations that foregrounded how artists who were “othered” in the United States sought out opportunities in the Eastern Bloc to forge alternative forms of solidarity and connection.

Jessica Horton (University of Delaware) provided a much-needed intervention to unsettle the binary logic of Cold War statecraft by introducing the concept of earth diplomacy, a form of advocacy derived from and insisting upon Indigenous cosmologies. Charting how the deployment of Native American art for US propaganda exhibitions abroad was alternatively used to suppress and support campaigns for Indigenous rights at home, Horton discussed the contribution of Luiseño artist Fritz Scholder to a USIA exhibition in Bucharest in 1972, during which time his unofficial travel to Transylvania resulted in a enigmatic series of paintings equating Native Americans with vampires. Presenting the Cold War as a legacy and continuation of European colonialism – with all sides seeking to modernize at the expense of human and ecological health – Horton’s cosmo-political perspective reinforced the truly planetary scope of Cold War diplomacy.

The conference organizers, Kathleen Reinhardt and Julia Tatiana Bailey, concluded the day by exploring entanglements of art, politics, and race through examples of Black US artists who chose to enter Communist Europe. Connecting artists including Oliver Wendell Harrington, Charles White, and Margaret Burroughs, this joint talk argued that state-funded socialist art practices in the GDR and Soviet Union provided various points of attraction, from offering employment and display opportunities denied in the United States due to political or racial discrimination, to providing examples of a people-focused visual language that might support the burgeoning African-American Civil Rights Movement. Opening further avenues of research, Reinhardt and Bailey suggested how these artists’ experiences and knowledge-gathering across the Iron Curtain might have been absorbed into the visualization of Black Power, which continues to reverberate in prominent artistic practices of the contemporary art world.

The conference concluded with the lecture performance Red-Black Thread by the artists’ collective Slavs and Tatars, introduced by Hilke Wagner, Director of the Albertinum. The performance encapsulated the spirit of the conference by elevating Russophone perspectives, specifically those from the Soviet Union and imperial Russia, over dominant Western interpretations to chronicle the international development of concepts related to Black identity. By probing interwoven histories and experiences of labor, race, and sexuality, the work recovers failed promises of convivial existence, and so leaves open the possibility of new understandings. Slavs and Tatars had a solo exhibition at the Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau and the Albertinum in 2018, which was accompanied by earlier lecture performances that can be watched here and here.

Above all, “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold” highlighted the extent of complex relations and negotiations that operated at different scales during the Cold War – from individual prints and photographs, to artists and curators, to institutions. To better grasp those cultural developments, art history will need to grapple with multiple levels of analysis if it is to continue to problematize inherited, ideological narratives that ultimately present far too simplistic a vision of history. More or less explicitly, depending on the talks, the conference placed considerable pressure on the validity and value of national- or state-based frameworks for art history. By the end of the day, it was far from clear that such geopolitical boundaries retain (if they ever had) any useful explanatory power, or if they are nothing more than analytical boundaries relied upon by habit rather than justification. When taken together, the papers implied the ongoing need for more finely tuned analyses of cultural production in the Cold War in order to account for the diverse forms of encounter that mark the transcultural interactions between artists, critics, and curators.

Also of interest:

The annihilation of Vinh City by US bomb raids offered an opportunity for experimental planning and for transforming the small industrial town into a model socialist city. The GDR’s ambitious task of comprehensive reconstruction involved working collectively on both the creation of a master plan and its realization in built form. Christina Schwenkel on the Quang Trung housing complex.

In 2022 and 2023, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden are fixing their gaze once again on GDR times in their research and exhibition project “Kontrapunkte” (“counterpoints”), funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. Based on their own holdings and the history of their collection, fresh perspectives are being developed on art in the GDR, how it was seen and the significance allotted to it in the past and present, with the addition of international viewpoints. To this end, a range of physical and digital formats are in the pipeline, information on which will be provided on this platform.

The same motif, again and again – Jane Boddy on two works by Eberhard Havekost that are currently on view in the study room of the Kupferstich-Kabinett, and on the (im)possibility of repetition.

![12 Uhr [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/d/csm_A_2007-88_r_3db174dfb2.jpg)

![Between Antifascist and Modernist Aesthetics in the Work of an Émigré [...] (Mary Ikoniadou) Between Antifascist and Modernist Aesthetics in the Work of an Émigré [...] (Mary Ikoniadou)](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/e/csm_Between_Antifascist_and_Modernist_Aesthetics_in_the_Work_of_an_Emigre__...___Mary_Ikoniadou__5365e271dc.png)

![Attitude and Doctrine: The Intergrafik as a Place for Demonstrations of [...] (Sophie Thorak) Attitude and Doctrine: The Intergrafik as a Place for Demonstrations of [...] (Sophie Thorak)](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/6/csm_Attitude_and_Doctrine__The_Intergrafik_as_a_Place_for_Demonstrations_of__...___Sophie_Thorak__093b8d01b7.png)

![Collaging Outlaw Exhibition: Steve Poleskie’s Aerobatic Sky Art in Warsaw [...] (Maria Anna Rogucka) Collaging Outlaw Exhibition: Steve Poleskie’s Aerobatic Sky Art in Warsaw [...] (Maria Anna Rogucka)](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/3/csm_Collaging_Outlaw_Exhibition__Steve_Poleskie_s_Aerobatic_Sky_Art_in_Warsaw__...___Maria_Anna_Rogucka__26fab727d8.png)

![Charles White, Civil Rights, and Black US Art in [...] (Kathleen Reinhardt/Julia Tatiana Bailey) Charles White, Civil Rights, and Black US Art in [...] (Kathleen Reinhardt/Julia Tatiana Bailey)](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/4/csm_Charles_White__Civil_Rights__and_Black_US_Art_in__...___Kathleen_Reinhardt_Julia_Tatiana_Bailey__d5885fe593.png)