Gutschmid’s plan was to donate the fountain to his native city Dresden as a gift commemorating the “gracious providence of Heaven”. The epidemic had been on the brink of approaching Dresden from the Oder river and the lower course of the Elbe. Apart from good fortune, Dresden may have benefited from the experience gained from an outbreak of the plague in 1680, after which the city council put forward its first Plague Order. This enabled epidemics to be fought by enforcing hygiene rules more strictly.

Semper, Gottfried: Der Cholerabrunnen in Dresden (um 1845)

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Andreas Diesend

To appeal particularly to Semper’s ambition, the benefactor wrote that he “wanted to exploit the fortunate circumstance that Dresden had an artist whose works earned him an acclaimed position in the art world”.

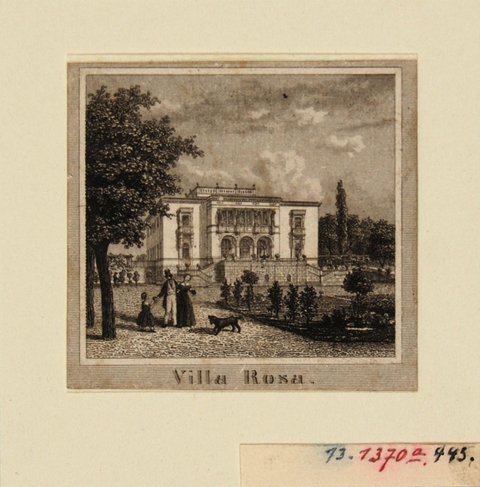

Gottfried Semper was born in Hamburg in 1803 and died in Rome in 1879. On 30 September 1834, he was appointed to the Chair of Architecture at the Royal Saxon Academy of the Arts. Before planning began on the Cholerabrunnen, he had already designed and overseen the construction of various important Dresden buildings such as the “Villa Rosa” (1839–40), the Halls of Antiquities at the Japanisches Palais (1836–38), Dresden Synagogue (1838–40) and the old Royal Court Theatre (1838–41).

Die Villa Rosa am Neustädter Elbufer (heutiger Ort der Grundschule am Rosengarten), Blick nach Norden (um 1860, Urheber nicht bekannt)

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

J. Riedel: Die Alte Synagoge von Gottfried Semper in Dresden am Hasenberg von Südwesten (um 1830)

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

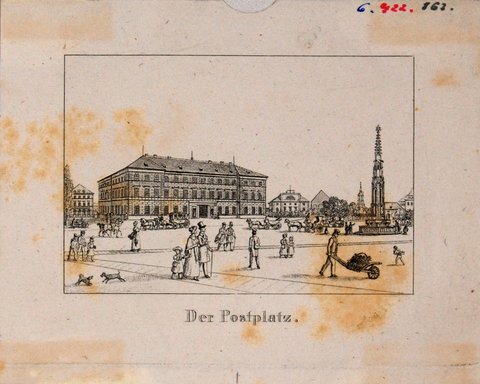

There was some discussion about where the fountain would be located and how it would fit into the cityscape. Semper preferred the square to the west of the historical city centre, originally known as Wilsdruffer Tor-Platz and renamed Postplatz in 1865. Once Dresden’s old city fortifications had been removed, Postplatz was an important, valuable urban space that would offer a good view of the monument. The soil conditions and supply of water for the fountain also played a role. On 26 February 1841, Semper informed the Ministry of Finance that Gutschmid intended to donate money for a public fountain from his private funds. Semper enclosed the plans, adding that further planning documents would follow.

Der Postplatz in Dresden, Blick nach Südwesten, mittig das Postgebäude und der "Goldene Ring", rechts der Cholerabrunnen, im Hintergrund die Annenkirche (um 1850, Urheber nicht bekannt)

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

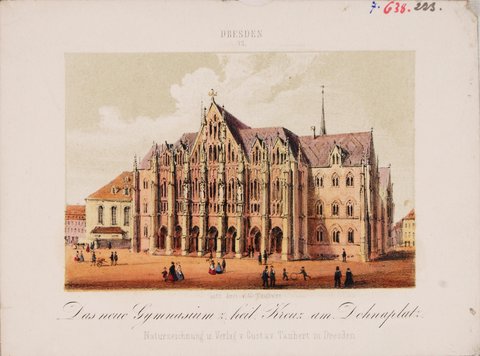

Between 1842 and 1843, the fountain was built at the point where the street leading to the old city post office met Wilsdruffer Gasse. Gottfried Semper, Karl Moritz Seelig and Franz Schwarz worked together to create one of Dresden’s first monuments in the High Gothic style. It was not until 15 July 1846 that it was officially presented to the then mayor Baltasar Hübler. The city’s few other works of architecture in the Gothic revival style included the Kreuzschule, built from 1864 to 1866 on Georgplatz by Prof. Christian Friedrich Arnold, one of Semper’s pupils (this was destroyed in 1945) and the Paulikirche, built by Christian Schramm from 1889–91 and also heavily damaged in 1945.

Gustav Taubert: Die Kreuzschule in Dresden am Georgplatz, Blick nach Nordosten (um 1870)

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

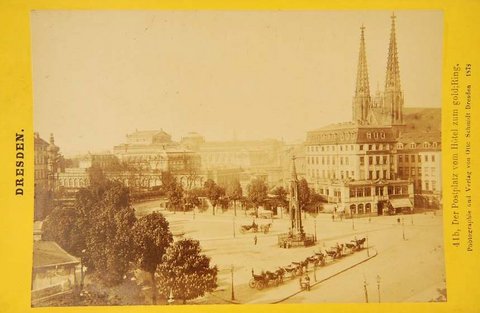

Otto Schmidt: Der Postplatz vom Hôtel zum gold; Ring (1873)

© Museum für sächsische Volkskunst, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The fountain itself essentially comprised two interwoven motifs: a pointed column, rising up like a pyramid, and a raised sacrarium of the kind seen in wayside shrines and sacrament houses as of the High Middle Ages. The sacrarium is made of stone and is 90 cm or almost three feet high. Four figures stand at the four sides of the fountain: to the east St. Boniface, Apostle to the Germans; to the south John the Baptist; to the west Saint Elizabeth of Thuringia and to the north Widukind, the first Saxon prince to be baptised. Beneath the figures there are Biblical verses. Water was seen as a symbolic force that healed the body and soul. The monumental functional element at the fountain’s heart is a roughly 16-metre (52-foot) column in the middle of an octagonal granite basin that is about 6.8 metres (22 feet) in diameter. The column is surmounted by a two-tiered finial.

Nordseite des Cholerabrunnens in Dresden mit Wittekind-Skulptur

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Jacob Franke

At the base, pulpit-like basins are held up by gnomes, with various mythical creatures spouting water above them. When the monument was built in 1843, the sculptor Karl-Moritz Seelig used Cotta sandstone, which was easy to work with but unfortunately weathered rapidly. Restoration work was required as early as 1869, and there were even thoughts of changing to bronze. However, this was rejected in an appraisal by one of Semper’s pupils, Prof. Constantin Lipsius, who did not want his master’s monument to be distorted by a change of material.

The fountain was fully refurbished and restored for the first time from 1889 to 1891, by the sculptor Franz Schramm. Hard Weser sandstone replaced the old stone, with the figural area made of Silesian sandstone. This was also the first time that the fountain was moved eastwards. In 1927, due to increasing traffic, the Cholerabrunnen was relocated entirely from Postplatz to the corner of Sophienstrasse and Kleine Brüderstrasse.

Detail des Cholerabrunnens in Dresden

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Jacob Franke

Though the fountain was right in the city centre, it escaped the 1945 bombings with only minor damage. Parts that had fallen off, such as the finial, were recovered from the rubble, enabling it to be restored in the 1960s. Between 1996 and 1997, further refurbishment was required to deal with vandalism and further signs of weathering to the sandstone.

To this day, the fountain at Postplatz commemorates Dresden’s good fortune in escaping the cholera epidemic of the early 1840s.

Also of interest:

What coins and medals say about epidemics

What we can learn from coins and medals goes far beyond discovering hidden hoards or studying the economic consequences of events. Such artefacts also tell us about societies’ beliefs, hopes and fears. Currently, an exhibition at the Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection) is devoted to the connection between coins and epidemics. Curator Ilka Hagen explains here what one has to do with the other.

Humankind and human diseases in the time before writing

Diseases are not only something that artists pick up on; they are also an important indicator for archaeological researchers. The traces they leave behind offer clues to the circumstances and ways in which people lived, playing a material role in proto-historic research.

Hula at the grave of the Unknown Soldier

Is it possible to react aesthetically to an event like the wartime invasion of the Wehrmacht? Sergej Paradjanov has tried to do just that. Born in Georgia and of Armenian descent, he made films about Ukrainian history. One can hardly find anyone who embodies the cultural pluralism in the title of the current exhibition "Kaleidoscope of History(s). Ukrainian Art 1912-2023" as much as he does. His film fragment "Kiev Frescoes" is part of the exhibition and was also featured in the digital prologue here on voices.