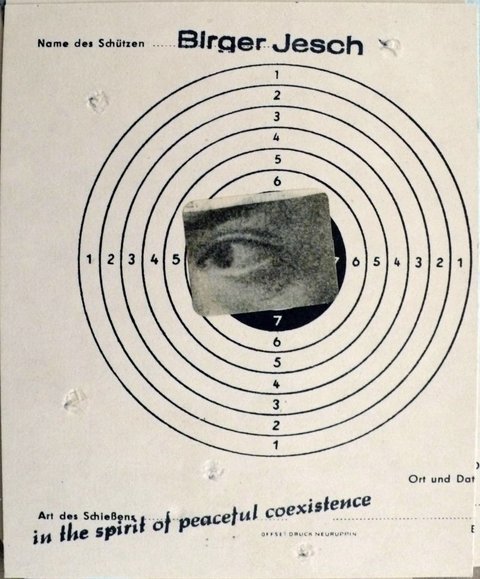

At the start of 1980, the Berlin artist Joseph W. Huber received a destructive work of art. The artist Birger Jesch sent him a postcard via the international mail art network that had lately emerged from towns such as Dresden and begun encircling the globe.

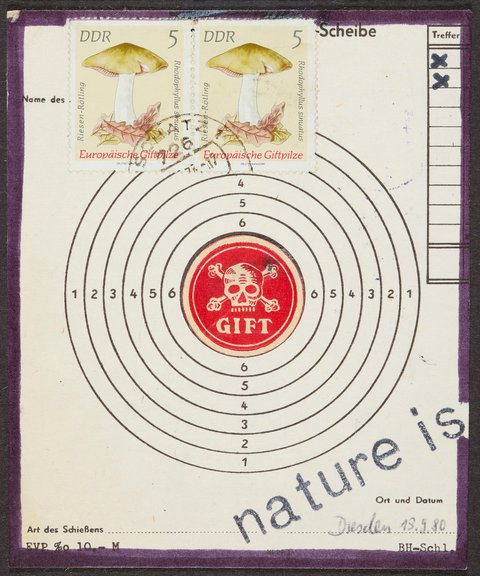

Birger Jesch: Postkarte an Joseph W. Huber, datiert auf 19. September 1980, recto und verso collagierte, bestempelte und handbeschriftete Schießscheibe, ca. 11 x 16 cm

© Mail Art Archiv, Staatliches Museum Schwerin (SSGK-MV), Kupferstichkabinett, Foto: Ulrich Pfeuffer

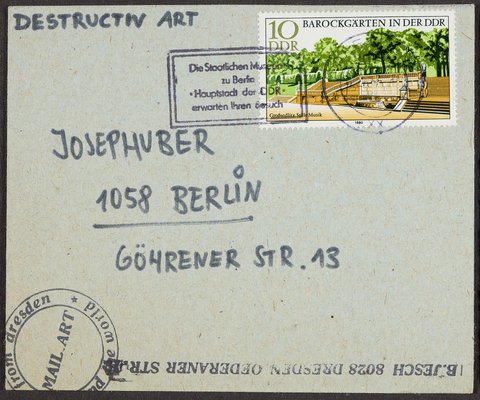

The front of the card, on further inspection a paper target for air rifle shooting competitions, is on the theme of nature. At the bottom right, in the space labelled “shooting type”, is the start of a sentence: “nature is”. The card itself brings the ending “poisonous” to mind. The shooting target has been given a black border like a sympathy card. A red “poison” sticker with a skull and crossbones sits squarely in the bullseye. Two old East German postage stamps from the “Poisonous European Mushrooms” series, each showing an inedible Livid Pinkgill, are stuck in the space for the shooter’s name. On the back of the card, a postage stamp invites visitors to the baroque gardens at Großsedlitz in Saxony and a standard postmark advertises Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. The postcard also promotes the mail art genre, which used the postal infrastructure and generally rather unusual, very much critical artistic content in an attempt to pervade traditional art institutions and genres – provoking postal censorship by the Stasi; the GDR’s Ministry for State Security.

Birger Jesch: Birefumschlag der Postkarte an Joseph W. Huber, datiert auf 19. September 1980, recto und verso collagierte, bestempelte und handbeschriftete Schießscheibe, ca. 11 x 16 cm

© Mail Art Archiv, Staatliches Museum Schwerin (SSGK-MV), Kupferstichkabinett, Foto: Ulrich Pfeuffer

1 Many East German citizens suffered from the restrictions on their freedom to travel that they later demonstrated against during the Peaceful Revolution of 1989.

(See also the 2024 conference Freedom (or lack thereof) to travel. Mobilities of artists during the Cold War, organised by Kerstin Schankweiler, Jule Lagoda

and Nora Kaschuba, Technische Universität Dresden and Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.) In an essay on postal surveillance in the GDR, the Berlin

mail artist Lutz Wohlrab cited some lines by the poet Reiner Kunze that were popular among artists of the genre: “Brief du / zweimillimeteröffnung / der tür

zur welt du /geöffnete öffnung du / lichtschein, / durchleuchtet, du / bist angekommen” (“Letter, you / two-millimetre crack / door to the world, you /

cracked crack, you / glimpse of light, / glimpsed, you / have arrived”) Reiner Kunze, “einundzwanzig variationen über das thema ‚die post‘”

(“Twenty-one variations on the theme ‘the mail’”), in: Die wunderbaren Jahre, Frankfurt am Main 1978, p. 123; cited after Lutz Wohlrab, “‚

Bitte sauber öffnen! Danke‘ Mail Art und Postkontrolle in der DDR”, in: Horch und Guck 2/38 [2002], pp. 42–46.) On the topic of mail art as a

network, see Kornelia Röder, Topologie und Funktionsweise des Netzwerks der Mail Art: seine spezifische Bedeutung für Osteuropa von 1960 bis 1989,

Cologne 2008; cf. Katrin Mrotzek and Kornelia Röder (eds.), Mail Art. Osteuropa im internationalen Netzwerk, exhibition catalogue, Staatliches

Museum Schwerin, Schwerin 1996.

2 see Sterre Barentsen, Miningscapes and Acid Lakes. An Environmental Art History of the late-GDR Dissertation, Humboldt-Universität

zu Berlin, Berlin 2023; see also Petra Lange-Berndt, “Nature is Life – Save It! Kollektivität und Ökologie in der DDR”, in: Kunstforum

International 263/Rebellion und Anpassung (2019) pp. 128–135; see Antonia Napp, “Der bedrohte Planet. Umwelt und Zerstörung als Thema”, in:

Kornelia Röder (ed.), Außer Kontrolle!: Farbige Grafik & Mail Art in der DDR, exhibition catalogue Staatliches Museum Schwerin, Cologne 2015, pp. 64–72.

3 Huber and Jesch largely shared the same views on conservation. In all, five submissions by Jesch appear in the seventeen posters of postcards in the

Nature is Life initiative; see Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv. no. 19795 Gr MA_03, inv. no. 19795 Gr MA_06, inv. no. 19795 Gr MA_07, inv.

nos. 19795 Gr MA_11 and 19795 Gr MA_15.

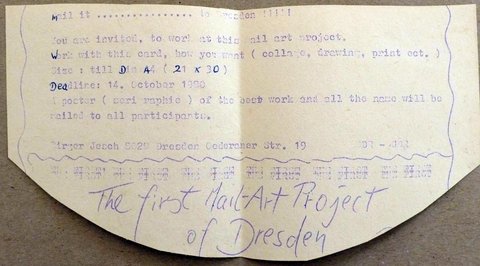

Birger Jesch: Mail-Art-Aufruf aus Briefsendung an Niels Lomholt, 1. Juli 1980, recto handbeschriftetes Papier, ca. 10 x 21 cm

© Lomholt Mail Art Archive

The organisational challenge facing Jesch came from the fact that mail art projects of this type were still relatively uncommon in East Germany. The international mail art community, meanwhile, had already established a modus operandi for such projects. First, postal invitations were sent out to activate the global mail art network on a “no jury, no fee, no return” basis. The hundreds of people who received them were then expected to send postcards or other works on paper to a private address or an exhibition venue where the works received were to be presented. The topic changed with each project while the conditions remained the same.

4 The “International Air Rifle Targets”, produced in the Brandenburg town of Neuruppin, were cut to the size of a standard postcard by removing the

competition table on the right-hand side. (See Link (22 May 2024))

5 See Birger Jesch, “Mißbrauch sakraler Räume für staatsfeindliche Zwecke”, in: Friedrich Winnes and Lutz Wohlrab (eds.), Mail Art Szene DDR 1975 – 1990, Berlin 1994, p. 96.

6 See Robert Rehfeldt, “Ursachen und Wirkung der Kunst in der Kommunikation – die Mitteilung progressiver Ideen per Post”, in: Bickhard Bottinelli (ed.), Die Post als Künstlermedium: mail art + Künstlerstempel, Kassel 1976, pp. 18–21.

7 Document “Maßnahmen zur Verhinderung pazifistischer Aktivitäten der evangelischen Kirche”, Dresden district Stasi administration, Dept. XX, 1

April 1982; cited in Heidrun Hannusch, “Operativer Vorgang ‘Feind’ – Wie die Staatssicherheit die Dresdner Mail Art Gruppe ‘zersetzte’”,

in: Friedrich Winnes and Lutz Wohlrab (eds.), Mail Art Szene DDR 1975 – 1990, Berlin 1994, p. 109.

8 See the memo in Jesch’s Stasi file from January 1981, kept at the Staatliches Museum in Schwerin, noting that Jesch had invited people from

Karl-Marx-Stadt (Chemnitz) to take part in a mail art exhibition. This shows that the Stasi had Jesch in their sights, but did not yet seem

to be sure what was going on with the mail art projects. The proviso must also be added that in some cases, more than one of the 300 invitations

were send to the same recipients, and that some recipients evidently chose not to take part in the project for other reasons. On this subject, and

regarding censorship, see for example the relevant correspondence between Jesch and Rehfeldt (Rehfeldt Mail Art Archive, inv. no. 4093 and inv. no. 4534)

and between Jesch and Lomholt (Link [22 May 2024]).

Jesch also subsequently launched a survey to find out whether the people in his network had taken part in the project, and their reasons

for doing so or not. I do not have any further details about the survey findings. ([22.05.2024]).

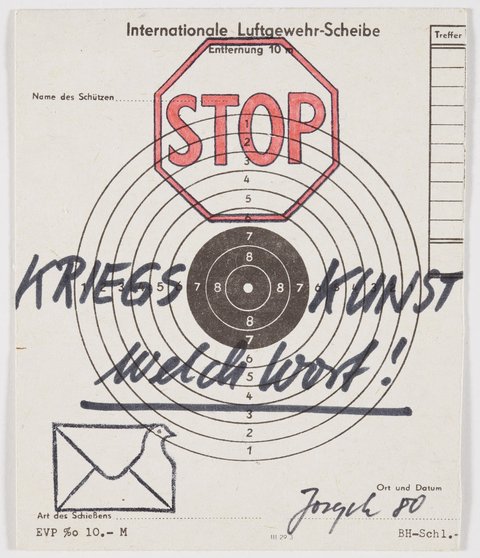

Joseph W. Huber: Postkarte an Birger Jesch, 1980, recto bestempelte und handbeschriftete Schießscheibe als Teil einer Bildertafel, ca. 12,5 x 16 cm

© MAIL ART ARCHIV, STAATLICHES MUSEUM SCHWERIN (SSGK-MV), KUPFERSTICHKABINETT, FOTO: ULRICH PFEUFFER

From a modern perspective, Stasi censorship was an arbitrary process of baffling complexity, as illustrated by one shooting target designed by Huber. The target is one of the entries submitted to the project that could have fallen victim to censorship according to the above criteria. The section of the target in the upper half of the picture is covered by a hand-drawn stop sign with red colouring-in. To the left and right of the bullseye, Huber has written “KRIEGS · KUNST” (see below) and beneath it the comment “welch Wort!” (“what a word”). The space labelled “shooting type” describes the artistic method used here through allegory; an envelope turning into a dove symbolises peaceful correspondence.

9 See Kornelia Röder and Lutz Wohlrab, “International Contact with Mail Art in the spirit of peaceful coexistence – Das pazifistische Schießscheiben-Projekt von Birger Jesch”, in: Zeitschrift der Geschichtswerkstatt Gerbergasse 18 /104 (2022) p. 23.

It is against that background that Huber takes a clear political position: his stop sign can be understood as a call to end the Cold War, while also conveying his general scepticism about the term “Kriegskunst”. On one hand, this can mean “war art”, i.e. cultural or artistic works (such as this one) that tackle the subject of war or are created during times of war. On the other hand, in military science it can mean “the art of warfare”; the strategic, operational and tactical planning and waging of wars. Huber is criticising the fact that the word attaches aesthetic value to military action; a pacifist attitude that is shared by Jesch and the authors of the other works submitted. From the start, the slogan behind Jesch’s project was “International Contact with Mail Art – in the spirit of peaceful coexistence”.

Birger Jesch: Mail-Art aus Briefsendung an Niels Lomholt, 1. Juli 1980, recto collagierte, bestempelte und verso handbeschriftete Schießscheibe, ca. 11 x 16 cm

© Lomholt Mail Art Archive

10 Dictionary entry on “pacifism” cited after Heidrun Hannusch, “Operativer Vorgang ‘Feind’ – Wie die Staatssicherheit die Dresdner Mail Art Gruppe ‘zersetzte’”, in: Friedrich Winnes and Lutz Wohlrab (eds.), Mail Art Szene DDR 1975 – 1990, Berlin 1994, p. 109.

11 Members of the Dresden mail art scene, such as Jürgen Gottschalk, Martina and Steffen Giersch and Joachim Stange, faced especially severe persecution from the Stasi. On this topic, see Jürgen Gottschalk,

Druckstellen: die Zerstörung einer Künstler-Biographie durch die Stasi (Vol. 5 of a series of monographs by the Saxon State Commissioner for the Records

of the State Security Service), Leipzig 2006; see also Heidrun Hannusch, “Operativer Vorgang ‘Feind’ – Wie die Staatssicherheit die Dresdner

Mail Art Gruppe ‘zersetzte’”, in: Friedrich Winnes and Lutz Wohlrab (eds.), Mail Art Szene DDR 1975 – 1990, Berlin 1994, pp. 109–114; see also

Lutz Wohlrab and Birger Jesch, “Feinde gibt es überall...: Stasi und die Mail Art in Dresden”, in: Horch und Guck 2/19 (1996) pp. 58–64.

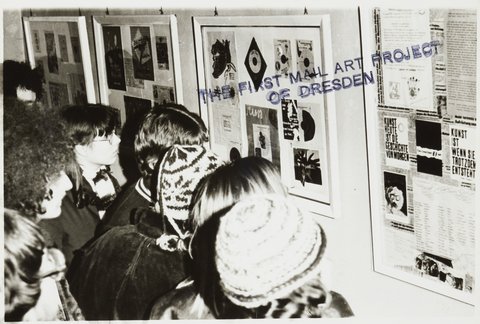

Birger Jesch: Schießscheibenprojekt, Ausstellungsansicht in der Dresdener Weinbergskirche, 1981, bestempelte Fotografie als Teil eines Leporellos, ca. 10 x 15 cm

© Mail Art Archiv, Staatliches Museum Schwerin (SSGK-MV), Kupferstichkabinett, Foto: Ulrich Pfeuffer

12 Birger Jesch, “Mißbrauch sakraler Räume für staatsfeindliche Zwecke”, in: Friedrich Winnes and Lutz Wohlrab (eds.), Mail Art Szene DDR 1975 – 1990, Berlin 1994, p. 96.

13 Ibid.

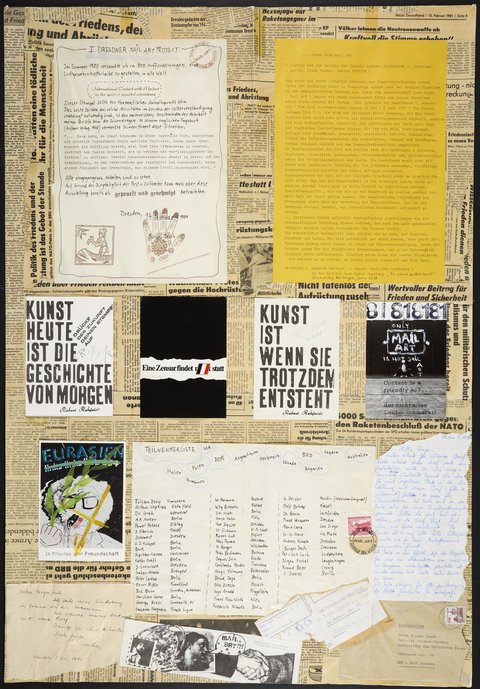

That was how the first exhibition of the shooting target project opened on 14 February 1981 in Dresden’s Weinbergskirche, also marking the first time a thematically complete mail art project took place in a public exhibition space in the GDR. The postcards that had been received were grouped and displayed in several picture frames – which was to become the standard means of presenting mail art at the time. The documentation poster seen at the right-hand edge of this photograph acted as a wall label. Jesch included a description of the project, an excerpt from the catalogue accompanying the exhibition at Galerie Arkade, four postcards, several excerpts from letters and a list of participants, all attached to a large-scale collage made from newspaper reports about the arms race.

Birger Jesch: Schießscheibenprojekt, Dokumentationsposter, ca. 1981, Collage

© Mail Art Archiv, Staatliches Museum Schwerin (SSGK-MV), Kupferstichkabinett, Foto: Ulrich Pfeuffer

By presenting his pacifist project in the setting of the Protestant church in the GDR, Jesch established what would become a constantly growing connection between the East German mail art scene and the church-supported oppositional environmental and peace movement; a movement that paved the way for and played a role in the Peaceful Revolution and German reunification just a few years later.

We would like to take this opportunity to thank Staatliches Museum Schwerin and the Lomholt Mail Art Archive for their cooperation and for providing the images shown here.

Auch interessant:

The Kupferstich-Kabinett is home to a significant collection of Cuban prints and posters that came to the GDR after the Cuban Revolution in 1959. While they were earmarked for the collection as part of the cultural exchange between the two socialist states, its director often did not welcome them with open arms. Olaf Simon, conservator at the Kupferstich-Kabinett, wrote about how they came to be part of the collection.

Musquiqui Chihying and Gregor Kasper’s film “The Guestbook” can currently be seen in our series on China as part of the “Counterpoints” project here on voices. The curator of the series, Mia Yu, interviewed them for us.

The garden at the Japanisches Palais is a place where human beings, plants and animals can be said to coexist. It is a place where ecological cycles can be seen and natural processes observed. In a museum’s inner courtyard, however, we are caught between teaching people about the topics of the future and preserving valuable art by preventing pest damage. How can that balance be maintained?