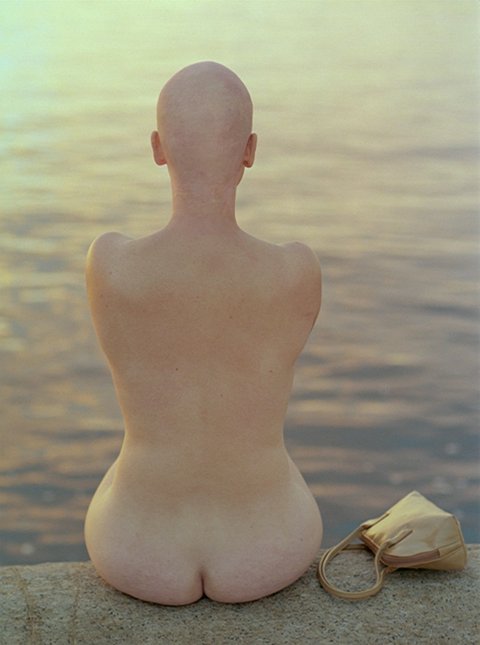

We can see the back of a person; she is naked and her body appears to be feminine. The concealed limbs give the figure the look of a torso. Yet, the constant breathing of the otherwise motionless body disrupts the impression that we are looking at a mere sculpture. It is astonishingly easy for us to identify with the almost abstract-looking body positioned at the edge of the calm yet flowing water. This perspective-taking is inspired, in particular, by the romantic motif of the figure seen from the back. Her gaze, the composition suggests, is directed at the vastness of the sea. Through it, we too are focused on the flow of the water.

A K Dolven: between the morning and the sandbag, 2002, video sculpture (still)

© Staatliche Kunstsammlung Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann / A K Dolven, Kamera: Vegar Moen

At least since Heraclitus, flowing water has served as a metaphor for the inescapable passage of time and the manner of all being. But the sea of A K Dolven lacks a clear direction. Playfully, though by no means less determinately, the lightly animated water conveys an understanding of time as a setting for the existence of various possibilities. As one might interpret Dolven’s video installation, the rigor of time does not simply consist of a mere determinism of succeeding events. Instead, if the sea is taken as a time metaphor, time, one might say, is presented as an inescapable medium of life. A first indication for such an interpretation can be seen in the limbless body that appears to be capable of moving freely only in the vastness of the water. Moreover, the modest dance of the sea takes up almost the entire horizon of the video frame.

Against the water, the small ledge upon which the delicate torso is seated appears to be only a brief stop. Dolven seems to tell us that, when on dry land, the body is limbless and incapable of movement. The smooth and hairless skin also suggests an existence befitting the water. Sitting on dry land, the person seems to be removed from her actual place of being. While the sea can be observed from the water’s edge, this comes at a price: standstill. Is it worth it? The video also hints at an answer to this question: The overview is merely superficial; it is impossible to comprehend, partition, or grasp the water. This is symbolically indicated by the limbless body. Moreover, the surface of the water, which becomes a canvas for the spectacle of light reflections, barely reveals anything about life in the water. If one is to take the image of the sea as a metaphor for the temporalization of being – that is, as an allegory for the fact that everything we experience takes place in time – then Dolven’s video sculpture reveals an urgent message. Rather than adopting a merely reflective attitude that attempts to survey life in its temporal configuration, it is necessary to dare to jump into the waves of the sea, in other words, into life which is fundamentally temporal.

There, in the water or in time, the self – represented by the streamlined torso – can move freely and explore existence. The exploration, however, is not conducted through the unrestrained gaze of the eye but through constant close contact with reality. Accordingly, orientation in time does not derive from a vantage point that surveys everything at a distance but arises from direct contact with things.

The handbag placed next to the torso could refer to an essential prerequisite for indulging in open temporization, to the free movement in the water: we have to renounce objects typically kept in handbags. The bag cannot be taken into the open sea. So, what do we have to leave behind? Symbolically speaking, the handbag makes us think of intimate and personal items, such as one’s identity card, membership card, or favorite photos. But in the water, these items do not serve us and can even hold us back. In a figurative sense, identity and personal memories can be an obstacle for our own unfolding in time in which we are faced with reality. Similarly, the necessary precautions taken for all possible situations – which is the reason why we pack hand cream, nail scissors, or lipstick – can get in the way. But as one might interpret Dolven, these anticipations of potential situations impede the free and spontaneous development in time. But another question is raised as well: What use is the handbag to the almost motionless torso, anyway? Without arms, the distance between the handbag and the body must seem insurmountable. Perhaps this is Dolven’s way of pointing out that memory, recollection, and outlook on the future are not really helpful, even when reflecting on one’s lifetime.

Ultimately, I would like to suggest, Dolven’s composition propagates an appreciation of the proper feeling of time, which can only arise in time by engaging with the temporalization of being. The reference to such a feeling of time, however, is indirect. At first, the calm breathing of the sculptural figure is the focus of attention. But the breathing does not express relaxation but rather trepidation. As I understand her work, Dolven wants to tell us that looking out to sea and reflecting on one’s lifetime can be overwhelming and can make us freeze. The resulting feeling of time is one of powerlessness, immobility, and incomprehensibility. It could perhaps be interpreted in the following way: At the water’s edge, the figure is apparently kept safe from the forces of time, but in doing so, she is almost degraded to a mere body that threatens to lose her vitality. In reflecting on our own life and time, we reify ourselves and view ourselves as objects.

The next question immediately follows: How is the proper feeling of time meant to be? And to which extent does Dolven provide information about this? My proposed answer refers again to the notion of the very being of the self. The presented figure seems only to be able to be true, that is, a feeling and moving body, in the water. It is as if Dolven wants to tell us that we can navigate and master time only by filling it and moving within it, acknowledging its inherent laws, and embracing its forces. Time is, therefore, not something to ruminate about but to be experienced. The figure belongs in the water; we belong in time. The tension between the idea of time as a powerful medium of life and the understanding of time as a realm of free development is not dissolved though.

Dolven also gives us heart. The water of the sea does not simply flow away. Rather, it presents itself as a spatiality capable of different directions. Based on such an understanding of the water as a parable of time, time becomes a realm of open possibilities. In reflection, that is, in thinking through all the possibilities, the abundance of freedom admittedly appears enormous. And yet, the sculptural figure also calls on us to venture into the array of emerging possibilities. The call may be subtle and not dictate a path. Even its promise remains open. In my opinion, however, this indeterminacy is how the composition indirectly refers us to one of the most primal feelings of time. It is a feeling that fundamentally characterizes our lives: hope, which carries us from moment to moment and which, ultimately, is indeterminate in content. In this respect, I find the presence of warm golden sunlight significant in Dolven’s video installation. From the time of ancient philosophy, notably in Plato, the sun has stood for the idea of the good. I have already indicated that it would be a mistake to view the light reflections as a direct expression of what is happening in the water, i.e., in time. Rather, I think the sunlight in Dolven’s work is meant to express the inner attitude with which we are to approach temporal events. In this way, I read the composition of light as an appeal to embrace temporalization in the light of the idea of the good. The idea of the good, I suggest, can be a cause of hope and joy for us. To re-engage with this underlying mode of temporality, that is, to embrace a joyfully attuned openness to what is to come as such, regardless of what looms ahead in the distance, could then ultimately be identified as the romantic motif of Dolven’s work.

The longing also addressed in this context is directed equally to the return to oneself and the future yet to be experienced. In Dolven’s visual language, this is no contradiction. Instead, the open sea is presented here as the natural habitat of the self. The inherent nature of the self thus lies in its optimistic open-mindedness for what is to come. It seems, however, that Dolven also wants to tell us that this open-mindedness does not simply overtake us but requires a leap. It is essential that the leap is not motivated by a particular idea or subject matter that proved suitable for reflective thinking. Gazing at the sea does not give us an idea of what awaits us in the water. Instead, it is necessary to take the leap, starting with an openness to encounters with others. Dolven’s composition is reminiscent of the famous topos of the leap into faith in the work of the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard: a leap that is not based on specific factual reasons or determinations but, instead, ultimately overcomes endless, rational doubt by allowing one to believe, trust, and – in my interpretation of Dolven – hope.

However, Dolven’s impetus should not be understood in religious terms or as a defense of irrationality. Instead, the potential leap into the water, in my view, can be interpreted as an act of entrusting oneself to existence. Such dedication to existence, as I take it, involves a recognition of the fact that much of life is only founded in encounters with others and cannot be anticipated, let alone resolved on our own in advance. Exposing oneself in such a way evidently is not without danger, as can be sensed in the figure’s nakedness and the vulnerability expressed therein. Still, the leap would not be a mere act of exposing oneself. Precisely because temporality inaugurates one’s very own natural field of time, the leap can be seen as a letting oneself go, as an acceptance of one’s lifetime. Dolven’s video sculpture appeals to this acceptance of the process of becoming who one is; a process in which the self opens itself to others as well as a different, non-anticipated self that is shaped by the encounter with others. And without promising anything in particular, Dolven’s work, as I perceive it, helps us see what we can hope for, if we take the leap: hope itself as a joyful state of existence, as the primal and felt recognition of the temporality of life itself.

[Translation by Erik Dorset]

This text is part of the exhibition “Feeling time. Experiences of temporality” (9.12.2022-27.2.2023), curated by Jane Boddy and Michael Griff.

Auch interessant:

Feeling time: How do we experience time? Punching a time-clock every hour for one year is an intense task, to say the least. Evelyn Wan elaborates on the relevance of Tehching Hsieh’s seminal work “One Year Performance” and considers how it resembles our current environments of labor.

The same motif, again and again – Jane Boddy on two works by Eberhard Havekost that are currently on view in the study room of the Kupferstich-Kabinett, and on the (im)possibility of repetition.

![12 Uhr [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/d/csm_A_2007-88_r_3db174dfb2.jpg)

In the storerooms of the Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde in Leipzig lie half a dozen of belongings of the former rulers of Sansanné-Mango, a town in northern Togo. how did they come to Leipzig? What was the role of the museum's former director, Karl Weule, in the translocation of this royal heritage? Can similar items be found in Berlin or elsewhere?

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/d/csm_Abb_4_quad_ba849ed3ea.png)