At the end of February 2024, not only the German media but even the New York Times reported on the RAF terrorist Daniela Klette, who had adopted a new name in Kreuzberg and led a supposedly humanitarian existence for 30 years. To be on the safe side, she had obtained an Italian passport. The only thing that really stood out about her was her enthusiasm for Brazil. At least that's what acquaintances said. As Claudia Ivone, she was a quiet but popular neighbour. As Daniela Klette, on the other hand, she belonged to the legendary guerrilla group about whose motives and connections to the GDR and to anti-Zionist combat units in the Middle East no one has any illusions since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Daniela Klette has never really disguised herself, but merely hid behind a few vowel-rich syllables: Claudia Ivone - apparently that's all it took to remain unrecognized in her neighbourhood and also to deposit a Kalashnikov, explosives and other war equipment in her apartment. If Klette's political intentions weren't so terrible, her strategy could be romanticized: It almost sounds as if she went to school with E.T.A. Hoffmann to make the unimaginable possible, even in the digital age.

From a historical perspective, Klette's successful deception of her persecutors is of course more reminiscent of numerous Nazi criminals who disappeared from the scene after 1945 under false names. They succeeded in doing what only very few of their victims were able to do. For example, Georges-Arthur Goldschmidt, who was born in 1928. His real name was Jürgen, but he had to translate his first name into French as a child when he was hidden from the Nazi henchmen in a remote boarding school in the Savoy Alps. And he survived, to this day.

By contrast, pseudonyms were of little use to the poet Gertrud Chodziesner. Like Goldschmidt, she came from a Jewish family and went down in literary history as Gertrud Kolmar. In the years after 1933, however, the artist's moniker did not even help her get published. During her lifetime, Gertrud Kolmar was only able to publish a few poems. The volume she compiled herself, Die Frau und die Tiere (The Woman and the Animals), was taken down immediately after its publication in connection with the November pogroms of 1938.

Perhaps this is why she tried to disguise seven of her most beautiful poems as translations from English. The cycle German Sea was written by a certain Helen Lodges, Kolmar claimed, and even faked English titles for each of the poems, which were written following a trip with the writer Karl Joseph Keller to Hamburg, Lübeck and the Baltic Sea at the end of 1934. In this way, for example, she transformed the fairytale-like Meerwunder (Sea Wonder) into a menacing Sea Monster. Nevertheless, the poems could only be printed years after the author's murder in Auschwitz.

It is little consolation that the dark times did not harm many of her manuscripts. Out of justified fear, Kolmar had hidden them with friends in good time. Her first editor was the writer Hermann Kasack in 1947. He carefully noted on the title page of the manuscript of German Sea: “Presumably not translations but original poems. Only faked as a translation etc. for political reasons by Kolmar in the thirties!” Kasack was not yet aware of Kolmar's late letter to her sister dated January 26, 1943, in which she removed all doubt that the poems were, so to speak, masked. In it, Kolmar recalled: “My last - and most beautiful - journey was to Hamburg, to Lübeck (following in Buddenbrook's footsteps) and Travemünde, and the most indelible impression was a winter night on a lonely seashore. My travel diary consists of seven poems, some of which are among the best I have ever found.”

The young writer Heinz Liepmann in Hamburg, who had gone underground after the National Socialists came to power, faced similar problems to Kolmar. As early as April 1933, his novels and plays were on the 'black list' alongside those of Bertolt Brecht, Alfred Döblin, Heinrich Mann and many other well-known authors. Using the pseudonym Jens C. Nielsen, Liepmann managed to get a comedy premiered, but this did not prevent his play from being banned. It immediately became known who had actually written it, which is why it was immediately cancelled. At best, Liepmann's performance meant that he was targeted even more by the SA from then on. He escaped to Paris. His “factual novel” Das Vaterland (The Fatherland) was published in the same year by an Amsterdam publishing house. The book is one of the earliest descriptions of the National Socialist camps, although Liepmann most likely only knew about them through reports from acquaintances, not from his own experience.

The Berlin student Kurt Lehmann had considerably more success with pseudonyms than Gertrud Kolmar and Heinz Liepmann. He fled to the Netherlands in 1934. One of his first publications appeared in the same year in Leopold Schwarzschild's exile organ Das neue Tage-Buch (The New Diary) alongside contributions from prominent refugees such as Ilya Ehrenburg and Joseph Roth - anonymously, as the Tagebuch eines Berliner Studenten (Diary of a Student from Berlin).

On the cover of the novel, which today would probably be marketed as 'autofiction', the author was not Kurt Lehmann, but a certain Konrad Merz. “Basically, the name Merz saved me,” Lehmann said looking back in 1977. “I made sure that no photo of me appeared anywhere, so that nobody knew who Merz was. Querido's secretary didn't reveal it either, but later she warned me.”

While the German occupiers searched intensively for Merz, they lost sight of the former student Lehmann. When he was ordered to be deported to Auschwitz, he reported to the murderous institution known as the “Central Office for Jewish Emigration” as ordered, but then disappeared. With a forged 'Persoonsbewijs', he could have identified himself as Karel Frederik van Gelder, resident in Amsterdam, in an emergency, but no one could have foreseen whether this could really have saved him.

However, his hiding place in a cramped laundry room in rural Ilpendam proved to be surprisingly safe. Here, Lehmann struggled until the end of the war with the fear of being discovered and the need to finally be able to move freely again. Sometimes he translated anti-fascist writings, occasionally he made notes in his diary, but above all he trained his body with the utmost discipline in the protective chamber.

After the end of National Socialism, this survival program became a life plan: Lehmann trained as a medical masseur and physiotherapist and set up a practice in Purmerend, which still exists today. He did not appear as a writer again until 1972. He gradually published three volumes of “tales” and “chats” by a “masseur”, the last of which had a title that sounds like a motto for Lehmann's survival story: Glücksmaschine Mensch (Joy Machine Human).

Had he really been saved not only by gymnastics and the courageous friends who hid him for years, but also by his false names? Unlike in the current case of the ruthless terrorist Klette from Kreuzberg, who even appeared in photos on the World Wide Web, we can only speculate. Speaking of the digital present: online, playing with protective pseudonyms and double identities has become so normalized to most of us that we no longer give it much thought.

Keep Reading:

Professor of Literature Roland Berbig finds a cloth decorated with Henna in the GRASSI museum. In his occupation with its label he encounters the 99 names of Allah and eventually the search for the 100th. That this quest has to do with labels is clear, but it is not written on the cloth. So where does protection come in?

What is to be protected is regulated by law in the state system. One person who knows this particularly well is professor and lawyer Edi Class, who explains in his text how law and protection are related to each other.

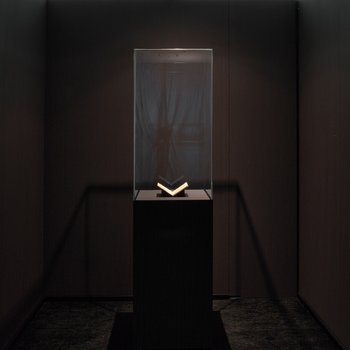

What do the Friedrich-paintings Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure) (1832), Hünengrab im Schnee (Dolmen in the Snow) (1807), Abtei im Eichwald (Abbey in the Oak Wood) (1818), Frau vor der untergehenden Sonne (Woman in Front oft the Setting Sun) (1818) and Nordische Landschaft/Frühling (Northern Landscape/Spring) (1825) have in common? Correct, they all include motifs recorded by Caspar David Friedrich between April and June of 1804 in a booklet, which is called the "Karlsruhe Sketchbook" today. Here you can flip through it.