For centuries, artists have been travelling to Italy, some going on their own initiative while others were sent south to study the arts at the expense of their aristocratic families. Starting in the 19th century, the trend increasingly arose for academies around the world to award a “Rome Prize” to selected artists; first men, then, from the mid-20th century, also women. Rooted in the humanist interest in the ancient world that arose in the Renaissance, the primary aim was for painters, sculptors and architects to study that period at the heart of the classical civilisation in Rome – the caput mundi or capital of the world. In later centuries, antiquities took on a less prominent role, but Rome retained this colony of international artists, with their animated discussion on aesthetics and lively to and fro of ideas. Although the goal on the surface back then was to carve out a place in the canon of art history, the background aim was always also a meeting of minds on shared cultural and universalist points of reference.

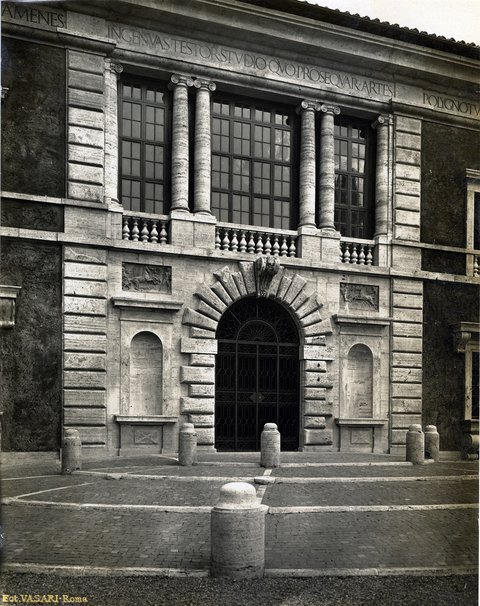

Die Villa Massimo

© Villa Massimo, Foto: Alberto Novelli

In 1666, France was the first country to found its Académie de France à Rome. Today in the Villa Medici, this was a local institution where artists could live and work. Under state supervision, their task was to make Paris beautiful, modelled on and copying Roman art. During the 19th century, other countries followed the French example. Pursuing a concept of an academy that was still shaped by nationalism and scholasticism, countries such as Spain, Britain, the US and Germany also created their own artist residencies in Rome. The stream of newly founded establishments never dried up: today, in fact, some 30 countries have academies and scholarship programmes in the Eternal City. In the 20th century, that led to the establishment of a globally unique cosmopolitan milieu of art and academia.

With the exception of the times of world war, a German Rome Prize has been awarded on a regular basis for a good 100 years, since the private foundation of the German Academy in Rome – Villa Massimo – in 1910. Today, the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media awards a ten-month scholarship to nine individuals or collectives selected by four panels of experts in architecture, the visual arts, musical composition and literature. Since 2008, practical grants have also been awarded for two-month stays by people from the applied fields of the creative industries.

Portal der Villa Massimo, 1914

© Archiv Zürcher-Pomardi, Foto: Maximilian Zürcher

The well-funded Rome scholarships include being immersed in a Mediterranean world, engrossed in a limited period of carefree creativity and accommodated at the Villa Massimo. As well as ateliers with adjoining apartments, the Academy provides a programme of events, helps bring projects to fruition, and organises exhibitions, performances, publications and cooperative ventures, giving artists a presence on the international and local stage. Their stay in Rome can provide inspiration, act as a guiding light and give artists the chance to share ideas and make their breakthrough. The Villa Massimo scholarship is indeed the most prestigious of all German art prizes, alongside similar but less extensive scholarships such as the Villa Romana in Florence or the Villa Aurora in Los Angeles.

The special appeal of Villa Massimo is related in part to its exceptional location: the German Academy in Rome is half an hour’s walk northeast of the city centre, on almost three hectares of parkland near Piazza Bologna. There, one of Rome’s most densely populated residential areas, built in the 1920s and 1930s, comes up against one of the city’s most exclusive belle-époque districts.

Hauptplatz umgeben von der Parkanlage der Villa Massimo

© Villa Massimo

At this spot, the latifundia – the Roman aristocracy’s estates – once gave way to the Roman Campagna, open countryside offering a view that stretches to the mountain ranges of the Apennines. After Rome became the capital in 1871, triggering a construction boom, the estates were sold and divided into smaller plots. Homes were built for the upper middle class, with flowering gardens under ancient trees. After the Second World War, these plots were further subdivided, and modern town houses appeared here and there. Today, this multifaceted district with its sprinkling of aristocratic estates, mansions in the Liberty style, ruins of ancient walls, Renaissance portals and modern houses is home to Villa Massimo. This takes its name from its park, all that is left of an estate once belonging to the old Roman Massimo family.

Making your way out to the Villa on foot, the first thing you come across is a tall wall whitewashed in an earthen shade. Following it, accompanied by the droning chirp of crickets, over soft beds of dry pine needles, or asphalt warped by roots and the heat, you arrive in front of the villa forecourt, closed off by a large inward-curving portal. Via a gatehouse at the side, you enter a world of total privacy: all that is visible from the outside is the dark-green crowns of the pine trees. The inside of the Villa is hidden from view.

Tempelartiger Bau im Garten der Villa Massimo

© Villa Massimo, Foto: Dennis Paeschel

That makes the effect all the more stunning when you enter the park. After a few steps, the shady gravel drive, lined alternately with enormous cypresses and antique vases, opens up onto a large, dazzlingly white forecourt also fringed by dark cypresses, ancient columns, fountains, statues, sarcophagi and the sweeping contours of the villa’s façade, decorated with white travertine marble. At this point, if not before, you will start to feel as if you have stepped onto a stage and are in a play.

Park der Villa Massimo

© Archiv Zürcher-Pomardi, Foto: Maximilian Zürcher

Swiss-born Maximilian Zürcher (1868–1926), who built this Renaissance-style villa in around 1910, was actually an artist. He started out as a painter and trod in the footsteps of Arnold Böcklin, kept company with the circle around Stefan George and built villas for artists in Tuscany. On what were once the green outskirts of Rome, he distilled the Romantic, mystical view of Italy into a Böcklinesque villa complex overlaid with symbolism. On what were neglected park grounds featuring nothing but a few windswept rows of trees, Zürcher took the remnants of original building elements and antiquities and assembled a staged Italian world apparently designed to make up for the brevity of North European scholarship holders’ one-year stay in Rome by heightening the impressions they took home. Today, a few of the quirky details have been dismantled for safety reasons, but originally Zürcher combined the ancient spolia to create surreal collages, for example by placing a seated statue on a monumental column. The garden and the villa thus form an almost metaphysical ensemble consisting of arcades, columns, sculptures, artificial temple ruins and deserted, idealised architecture positioned in paths and hedges arranged to create a multitude of vistas. The astonishing ensemble can be interpreted similarly to De Chirico’s dream-like contemporary cityscapes.

Far from imperial and papal Rome, far even from the palaces of the nobility, nestling among the homes of the petit bourgeoisie and the upper middle class, Villa Massimo’s location, too, bears witness to the fin-de-siècle repositioning of art and the art market. The change in the conditions in which art was produced is also anticipated by the functional residential ateliers concealed behind hedges and fountains at the rear of the villa forecourt. The long, sweeping wing of the building is reminiscent of an industrial production line, offering each worker plenty of space, but only in series. Perhaps its design was based not only on functional considerations, but also on the idea of artists searching for something together, and spurring one another on. This impression, which clashes with the concept of creative solitude and individuality, was once seen as jarring, but today it may be more in line with our new understanding of collective work.

Atelierflügel der Villa Massimo

© Villa Massimo, Foto: Alberto Novelli

With its two sets of facilities – the villa and the ateliers – Villa Massimo provides spaces for both otium and negotium, leisure and business, making it the perfect place for artistic inspiration and work. To this day, as a site for free reflection and creativity, it is in line with the enlightened, philanthropic intentions of the Jewish couple who founded it: Eduard and Johanna Arnhold.

Also of interest:

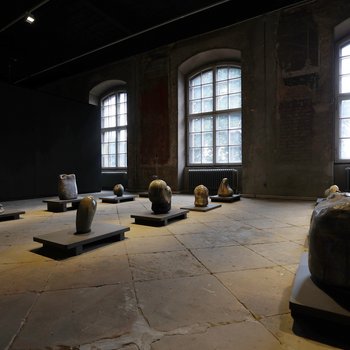

The firing of clay is one of the earliest technologies discovered or invented by man. A variety of work featuring ceramics as well as film and images created by Rome Prize winner Benedikt Hipp will be among the exhibits on display as part of the new exhibition “Eppur Si Muove – Und sie bewegt sich doch” at the Japanisches Palais (Japanese Palace), which happens to be the original location of the Porzellansammlung. In the following, Hipp offers insights into how he himself experiences and observes the creation of his ceramics – from collecting clay to the fired object.

Quotes from four passages of the novel Obwohl alles vorbei ist (Though Everything Is Over), published in spring 2023, can be read on posters around Dresden. This intervention by the writer Franziska Gerstenberg is part of the exhibition “Eppur si muove – And yet it moves”.

In many ways, Tom Hunter’s “Woman reading a Possession Order” seems to capture the effect of Vermeer’s original painting “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window”. Yet if one looks more closely at Hunter’s photograph from 1997, differences become apparent. Jane Boddy on an iconic image and its contemporary appropriations.

![[Translate to English:] Tom Hunter, Woman reading a Possession Order, 1997.](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/c/csm_Abb3_Tom_Hunter_Woman_Reading_a_possession_order_e8db018977.jpg)