What we can learn from coins and medals goes far beyond discovering hidden hoards or studying the economic consequences of events. Such artefacts also tell us about societies’ beliefs, hopes and fears. In the ancient world, for instance, deities of healing such as Asclepius (known in Rome as Aesculapius) or Hygieia (in Rome: Salus) were not just worshipped in temples, but also depicted on coins, especially in times of terrible diseases or epidemics.

![[Translate to English:] Asklepios and Telesphoros [Translate to English:] Bronze medal, the relief of which shows the holy Asclepius. On the right he holds a large, almost club-like staff towards the ground, with the snake coiling around it (Asclepius' or Asclepius' staff), in front of his left stands the small Telesphoros with hood and cape. The inscription reads: "ECOLES DE MEDECINE".](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/c/csm_1a_85d86b4794.jpg)

B. Andrieu/ J.-M. Jouannin, Representation of the god of healing Asklepios and Telesphoros, medal 1805, MK, Inv.-Nr. BUC523

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Münzkabinett

There is a very good chance that coins with motifs of this kind were used as amulets to protect against epidemics. The legends inscribed on them do not refer directly to a particular epidemic, however, but are broadly dedicated to the health of the emperor (Salus Augusti) or to good health in general. Many of the symbols that are today still associated with medicine and healing have their origins in ancient times. Probably the most well-known is the Rod of Asclepius, with a snake curling around it. The snake represented the deities of healing; it was associated with rebirth and immortality but could also be seen as a symbol of life and death. There was a good reason why the Ancient Greek word “pharmakon” meant not just “remedy” but also “poison”.

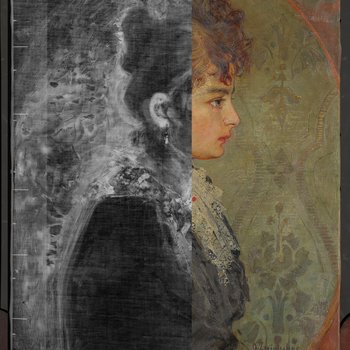

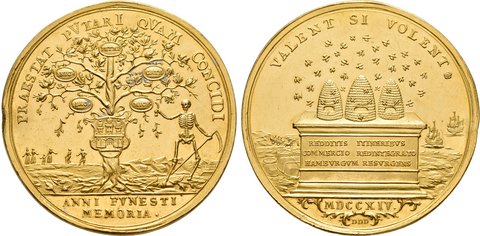

While no mediaeval numismatic artefacts have survived that directly relate to the Black Death, city medals appear during the early modern period with references to the plague. Unlike the coins from antiquity, these actually name the “plague years” on their obverse or reverse.

J. Reteke (?), Bankportugaleser 1714, Gold (Sammlung Brettauer 1381)

© Institut für Numismatik und Geldgeschichte Wien

They often show the city or town hit by the disease, sometimes combining depictions of death with imagery representing rebirth. This is shown especially clearly by a medal from the Hanseatic city of Hamburg. On the obverse (front), Death is plucking leaves from the tree of life. On the reverse, beehives and departing ships represent the return of trading, and thus the end of the epidemic. The legend on the obverse, “Praestat putari quam concidi” (“Not cut down but cut back”) expresses the hope that Hamburg has survived the plague.

There are also city medals from during the 19th-century cholera epidemics. The images on these rarely focus on death, instead increasingly depicting care for the sick. The scenes portrayed on the medals become more relatable and personal, moving away from the fate of the town as a whole and thus becoming more moving as they reflect human vulnerability.

![[Translate to English:] Merits of Dr. Ciancia in the cholera epidemic in Genoa [Translate to English:] A bronze medal whose relief shows a lying sick person held by a woman who gives him a drink from a vessel to his mouth. The clothing and vessels have an antique appearance. Above it is written "EPIDEMIA COLERICA 1884 IN GENOVA".](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/f/csm_3a_a5c4f3cbf5.jpeg)

P. Ferrea, medal 1886, bronze, Merits of Dr. Ciancia in the cholera epidemic in Genoa (Brettauer 1711)

© Institut für Numismatik und Geldgeschichte Wien

Over the centuries, the way we process epidemics has changed. This is especially clear from the medals that come after the early modern period. There is a certain continuity between the plague medals from this era and ancient depictions of the deities, the difference being that those deities are replaced by St. Sebastian and St. Roch or scenes from the Bible. As the state healthcare system increasingly developed, religious motifs began to fade into the background, but they have still not gone entirely. An emphasis on scientific research and on nursing can still be seen in the coins and medals minted during the coronavirus pandemic. Many offer thanks to healthcare workers or are dedicated to scientists.

![[Translate to English:] Merits during the Corona pandemic [Translate to English:] Medal with ribbon: In the center of the coin is the Aesculas staff with snake, which is in front of a perspective global map, in the center of which is North America (?). The motif is surrounded by laurel. In the outer ring in the upper semicircle is written "HONORARY SERVICE" , in the lower "The fight against the pandemic".](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/f/csm_4a_b3cd4a6ec6.jpeg)

Ukraine, Medal with ribbon 2021, merits during the Corona pandemic

© private

Also of interest:

Ivan Kavaleridze has played a significant role in Ukrainian culture. His name, however, is little known in contemporary Ukraine, and few people have heard about him outside the country. Currently, excerpts from his film "Prometheus" can be seen here on voices and in the Albertinum, the model for one of his sculptures is on display in the exhibition "Kaleidoscope of Historie(s)". Stanislav Menzelevskyi on Kawaleridze as a filmmaker and the banning of his movie Prometheus.

Seventeen works from the artist’s oeuvre – which originally comprised around 150 paintings – were examined in the research project “Oskar Zwintscher (1870–1916). The Unknown Masterpiece” by the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in the Albertinum, funded by the Friede Springer Stiftung, subjecting them to art technology analysis in the painting restoration workshop. Here you can gain insight into the complexity found in the structure of Oskar Zwintscher’s paintings.