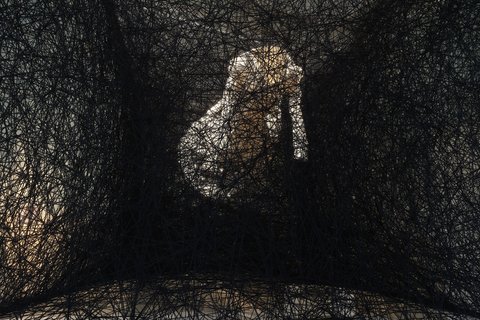

Chiharu Shiota: "Inside, Outside" im Wasserpalais des Kunstgewerbemuseums in Pillnitz 2022

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Foto: Felix Meutzner

Mrs. Shiota, we currently have two installations of yours on display in two 18th-century Saxon castles, which, in contrast to classic white cube galleries, do not take a back seat as a backdrop, but instead enter into a kind of dialogue with the works exhibited within them. Do you find such juxtapositions appealing or do they actually repel you? Overall, how would you describe the relationship between the space your installations create and the space that accommodates them in each case?

I like any space that is a little out of the ordinary. I like old spaces because they give me inspiration. The curators have chosen beautiful rooms for both works and I think the works benefit from the space. As an installation artist I generally depend on the room very much. Without the space I cannot make anything, and it would be boring if every museum had the same white cube. I worked in old churches and even in a cave, and with the difficulties that this brought along, I also had the chance to develop something new. I love large-scale spaces and can put all my energy into them.

Chiharu Shiota: "Zweite Haut" in der Ausstellung "Raumschiff Hubertusburg" in Wermsdorf 2022

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Foto: Jacob Franke

In both cases currently on display at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, we are dealing with highly complex structures, one consisting of a multitude of windows and the other of a labyrinthine web of black thread. How do you actually document the construction and dismantling of these installations? Are they always completely identical or do they instead emerge anew to a certain extent each time?

I don’t document my process and if it were only myself working, I wouldn’t also make sketches before the installation. I would just go to the room and start there. When I recreate my works, I make them anew. But the two works you are mentioning are part of your collection and the museum’s team also has to install it when I am not around. My assistants installed “Inside, Outside” with the team from Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden three times and it has been documented. This time, it was your team that installed it without anyone from my team. I am very happy about the result. So there is a need for documentation, but the museums usually take care of it.

The installation “Inside, Outside” in the Wasserpalais in Pillnitz is composed of old East Berlin windows with wooden frames – everyday objects, in other words, that have done their service and have now largely been replaced by far less individual plastics. The one in Wermsdorf is made of black acrylic thread, an industrial product whose quality lies precisely in its continuity and uniformity. What is your personal relationship to serialization?

It is two different things. The kind of string I use doesn’t matter to me. Yarn is just the material that I use to make my art. I wanted to be able to draw in the air, that’s how it started. It needs to have certain qualities, but other than that I can work with any kind of yarn and it makes no difference if it is cotton, acrylic or wool. This decision is often made by the institution and is a matter of fire safety and the budget. I don’t think Picasso was deeply interested in the cultural connotation of the paint he used, and I keep it the same. Of course, with the windows it is a different story. I found them in Berlin. I collected them for weeks from construction sides. I was first interested in the windows and wanted to create something out of them.

Chiharu Shiota: "Inside, Outside" im Wasserpalais des Kunstgewerbemuseums in Pillnitz 2022

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Foto: Felix Meutzner

I also ask this because I find that the use of everyday objects in your work testifies to what Walter Benjamin once called the “aura” of the work of art and famously declared had been made obsolete by serialization and reproducibility. The work of art, which previously established the “unique appearance of distance, however near it may be”, loses that distance with the advent of serialization. It seems to me that “Inside, Outside”, like other artworks of yours in which everyday objects are used, is precisely about how the distant and the unique inscribe themselves in supposedly serial objects and are brought nearer. The people who have looked through them, the marks seen on the frames, the dirt on the glass, the cracks: the individual and the historical emanate from everything. Do you see this part of your artworks as resistance against something that is in danger of being lost?

I do not see the seriality with the windows; each of them is different, and in that variety, I can see the people behind them. When I found the windows, I was asking myself: Am I inside or am I outside? How do you know which side you are on? They were taken from houses in East Berlin and the people living behind them were living in another reality. I was interested in borders at the time. Because a border is always two borders; each side has different rules on how to cross it. It became very clear again during Covid. There is one rule to leave Germany and, for example, another one to enter Japan. I am interested in the many layers of reality around me. Our culture invented clothes and houses to separate ourselves from the world. When I came to Germany, I learned that my identity depends on my surroundings. So, I was asking always: where is my core? Am I myself behind the window or outside on the street?

Chiharu Shiota: "Inside, Outside" im Wasserpalais des Kunstgewerbemuseums in Pillnitz 2022

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Aufnahme: Felix Meutzner

In the centre of the window swirl there is a chair, but you can’t sit on it because it is completely surrounded by windows. The arrangement resembles a panopticon (meaning the prison design that is popular as a philosophical model), but the perspective is reversed. Instead of the all-seeing position in the centre, as we move through the swirl we are given multi-perspective, multi-framed, overlapping views of the centre. In view of the history of West Berlin, the surveillance apparatus of the Stasi, and the isolation of East Berlin in such close proximity to the West, the whole thing takes on a highly political dimension. Whose position actually corresponds to that of the chair in the vortex of windows, and which position is ours?

The objects I use in my work are often placeholders for people. When you put in a chair, it is immediately like there is someone else in the room. In earlier works I made houses out of the windows, but it was somehow too literal. I wanted to create a more interesting space and choose the spiral. I do not consider myself a political artist. I make art from my experience. It is a far more personal and intimate process. When I make art I have no message, I do not think of my audience. I want to create something beautiful and unseen, and I have my motives to do it in a certain way. But I also feel that I do not need to overexplain them. A chair is a familiar object. People will feel something when they see my work, and whatever they feel is right.

Chiharu Shiota: "Inside, Outside" im Wasserpalais des Kunstgewerbemuseums in Pillnitz 2022

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Foto: Felix Meutzner

Both installations make space tangible as something fragmentary, which appears not so much as a continuum but as dissected parts. That gives everything a dreamlike, unreal quality. It is said that you switched from painting to sculpture because of a dream. Would you say it was a nightmare, and are your current installations actually also dreams made real? And if so, do you sleep better now?

I sleep quite well, thank you. That crisis was 30 years ago. I always wanted to be a painter. There was series about famous works of art – mostly paintings – in the Sunday newspaper and I collected and admired them in my early teens. So it was very clear which medium I wanted to turn to. But having studied painting for a while, I felt like I could not connect to the medium. Like every painting I made was someone else’s work and I wanted to make my art. Of course, the school setting had contributed to this feeling. I felt that I could not paint any more and was looking for a new way to express myself. The answer came to me in a dream. I dreamt that I was inside a painting, and when I woke up the next day, I made the performance “Becoming Painting”, where I covered myself in red enamel paint and tried to become one with a canvas. My current installations are not inspired by dreams. They are inspired by my thoughts and questions and life in general. I started using thread because I wanted to draw in the air. So, in a way you enter a drawing, and the dream lives on.

Chiharu Shiota: "Zweite Haut" in der Ausstellung "Raumschiff Hubertusburg" in Wermsdorf 2022,

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Foto: Jacob Franke

The installation “Zweite Haut” (“Second Skin”), which can currently be seen in Wermsdorf in the exhibition “Raumschiff Hubertusburg” (“Spaceship Hubertusburg”), is a dense weave of black threads, which not only divide space, but at the same time have a supporting function, as if the “spaceship” is not flying through the cosmos, but is being carried by it. Everything is interconnected. In contrast, we learn to imagine space mathematically, as a three-dimensional emptiness that we can fill and cross freely. Do we have a distorted idea of what space actually is and do you understand space in principle as a “second skin” that surrounds and carries us?

Our clothes are our second skin and our house is our third. They are the borders that we use to protect ourselves from the world, I believe. So, the idea refers to questions of identity rather than ones of weightlessness or space. But your observation about space is true too, in the sense that my weaving does have this sense of infinity. I know an installation is finished when I cannot see the end of it any more. I like the simultaneity of vastness and detail. I think this is what reminds us of space when people look at my work.

In the use of the red, black and white threads in your works, you employ quite clear colour symbolism. Black represents the cosmos and the night sky, which is why "Zweite Haut” fits so well with the exhibition “Raumschiff Hubertusburg”. Is the colour of the window frames of “Inside, Outside” symbolic in a similar way?

My colour symbolism was a little born out of being asked in interviews what the colours mean. I did not invent this connotation; they are also standard associations with the three colours. Nor do I decide which colour to use because I want the work to be seen in a certain way to begin with. There are works with dresses in red and in black and in white. They are all dealing with the same things. Whether you call it space or the night sky, identity, connectedness, belonging, family, or a new beginning. Always the underlying question is: Who are we, what are we doing here and where will we go when we die?

We’re happy to give you this opportunity to finally clear up this long-lasting misunderstanding.

The materials of the two works (windows/threads) are ubiquitous metaphors of the digital. Could you imagine working digitally as well, and designing virtual spaces that can then be visited with VR glasses, for example?

No, I cannot imagine that at the moment. I feel the work would miss the visible labour that went into it.

Chiharu Shiota: "Zweite Haut" / "Second Skin" in der Ausstellung "Raumschiff Hubertusburg" in Wermsdorf 2022

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann, Foto: Jacob Franke

Last question: What are you working on right now?

I am currently in Japan, where I installed three exhibitions in the last weeks. Other than that I am already busy working on ideas for installations for the exhibitions that will open in the second half of 2023. I am currently interested in working with water and adding movement to my installations.

We are looking forward to that, of course. Thank you very much for the interview!

The questions were asked by the Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann's team and SKD's digital curator Jacob Franke.

Also of interest:

As time goes by, contemporary art too is aging. Often one has to deal with works that are ephemeral and perishable, as well as time-based media and materials. We’ve spoken to Franziska Klinkmüller, the conservator in charge of the Schenkung Sammlung Hoffmann at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, about the challenges of restoration of contemporary art and aspects related to sustainability.

![[Translate to English:] Ernesto Neto, the house, 2003, exhibition view Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/e/csm_IMG01_Neto__Ernesto__the_house_SHO__01056_99_9fe9d0bcc4_22a5412168.jpeg)

What remains of us? Currently quite a lot. In her film collage "Die Hüter des Unrats - eine kurze Geschichte des Abfalls" (The Guardians of Garbage - A Short History of Waste), which can currently be seen at the Japanisches Palais, Susann Maria Hempel takes a sarcastic look at the way we deal with waste and its ecological consequences. About the stomachs of predatory fish, chickens and giant tortoises as an archive.

What happens when you give museum audiences a stack of pencils, a few sheets of paper, and an entire room lined with white paper? Dresden artist Artourette did just that as a part of the Children's Biennale at the Japanisches Palais.