This article was written by Elias Aguigah, Yann LeGall and Jeanne-Ange Wagne from the department of Modern Art History at the Technical University in Berlin. It is the result of research led as part of the DFG-AHRC-funded project The Restitution of Knowledge, a collaboration between the TU Berlin, the University of Oxford and the Pitt Rivers Museum. By inquiring into museum storerooms and archives, The Restitution of Knowledge documents and rethinks the history of ‘plunder’ of former African colonies and addresses its legacy in ethnological collections, with a particular focus on loot and spoils from so-called 'punitive expeditions'.

In its attempts to address its colonial heritage and its participation in racist Eurocentric discourse, the Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde has begun a process of self-reflexivity and has solicitated artistic interventions to criticize, comment on, and “re-invent” its museal practice, as the title of one of its latest exhibitions maintains. Still, considering the huge number of African artworks, belongings and ancestral remains snatched by colonialists in its holdings, a long and strenuous path lies ahead. The museum bears an ethical responsibility to address histories that have been overlooked, acknowledge its participation in the colonial project, and take a stand on the presence of loot within its walls.

In the storerooms of the Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde in Leipzig lie half a dozen of belongings of the former rulers of Sansanné-Mango, a town in northern Togo. Among them, a silk brocade decorated with gold, reportedly owned by the ‘Djamarbu’ royal family for three hundred years,1 five war garments ornamented with so-called ‘amulets’ and several weapons and personal belongings.2 This material heritage of the Anufôm is part of a larger collection of 1,700 items from the former colony of German Togoland, attributed to the officer Gaston Thierry. They were packed in forty-six crates that landed at the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde on 14th August 1899.3

These belongings from northern Togo have been at the heart of critical research by Ohiniko Mawussé Toffa on the mechanisms of ethno-colonial collecting in German Togoland. On his advice, the members of the project ‘The Restitution of Knowledge’ undertook research in three different German museums to reconstruct the history of these belongings and expose a context of colonial violence. We asked ourselves: how did they come to Leipzig? What was the role of the museum's former director, Karl Weule, in the translocation of this royal heritage? Can similar items be found in Berlin or elsewhere? How did Gaston Thierry lay his hands on these personal. belongings and what was the lieutenant doing in northern Togo?

Sansanné-Mango / N’Zara

Sansanné-Mango was conquered by the Anufôm and their leaders Na Bièma Bonsafô and Na Soma in the twelfth century of the Islamic calendar (i.e. mid-eighteenth century of the Julian calendar). The two leaders and their followers had left Ano in today’s Ivory Coast. Some believed they were engaged by a ruler in the Mamprussi region as mercenaries that fought for him, others maintain they left because of a dispute over lineage and succession.4 In any case, the Anufôm did not go back to Ano. They settled on the west bank of the Oti River, and baptised their town N’Zara, which is today the most common name used by Anufo speakers.5 The official name of this town today, Sansanné-Mango, comes from an enduring spelling mistake of the Hausa word sansani meaning ‘war camp’. Depending on the perspective, both N’Zara and Sansanné-Mango will be used henceforth.

Biema Asabiè and ‘treaties of submission’

It was Biema Asabiè who ruled over N’Zara when colonialists first set foot in the region.6 He was a descendant of Bièma Bonsafô and therefore the political and military leader (called fémè). He first witnessed a British expedition led by the Fanti man George Ekem Ferguson. Then, a year and a half later, another expedition arrived in N’Zara at the height of the rainy season, in January 1895. The pale men leading the convoy were two thirty-year-old Germans: a soldier with a long and unpronounceable name,7 a white-collar administrator called Hans Gruner who, despite not knowing much about medicine, liked to be called ‘Doctor Gruner’, and Adolf von Seefried, who started taking notes on local Anufôm culture and languages.8

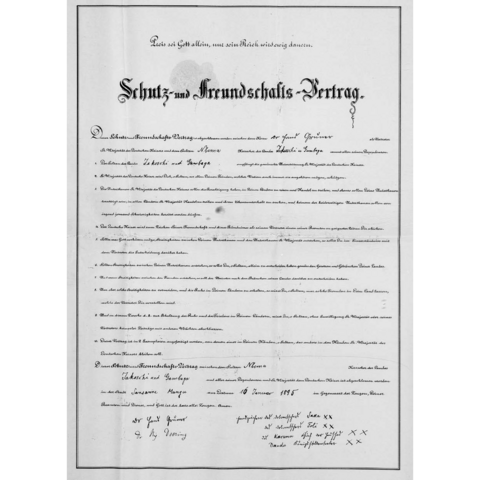

Scan der deutschsprachigen Version des sog. „Schutz- und Freundschaftsvertrags“, unterzeichnet von Hans Gruner, Gouverneur Doering (links), „Daudu, Königsstellvertreter“, dem „Karamu, Chief der Haussas“ und den beiden Übersetzern, Saka und Foli

© Bundesarchiv, R1001/3332

The expedition had brought presents to Biema Asabiè and asked for supplies for themselves and their African soldiers. They were loaded with firearms and called him, the religious leaders (called karamò) and other noble families of N’Zara for an official meeting. They handed him over a piece of paper, something they called a ‘treaty of protection and friendship’. The fémè and his counsellors were asked to put a sign where the Germans had written their name in a curious manner, from left to right.9 Perhaps wary of the implications of this piece of paper, Biema Asabiè did not sign it personally. Other local leaders, appended their signatures, including the karamò, which the Germans called ‘Imam’. African leaders probably considered them as simple trade agreements or signs of friendship rather than an official surrender of their authority and territories to European interests. The Germans, however, considered those signatures as an official acknowledgment of their political control over this region, i.e. material evidence that would allow them to claim authority over this important trading centre against French or English counterclaims.

To challenge colonial language, Tanzanian historian Buluda Itandala labelled those pieces of paper ‘treaties of submission’.10 In the paper’s own terms, this contract would allow the Germans to pass through his territory and engage in trade. The ten clauses on this agreement mention neither corporal punishment, nor decision-making power of Europeans on local politics and religion. A few months earlier, in a letter sent to his superior at the Colonial Department of the German Foreign Office, Hans Gruner himself had admitted: ‘Every one of those treaties is simply a piece of paper. They only gain meaning whenever diplomacy makes something out of it.’11

Right after the German visitors left N’Zara, another expedition arrived, this time with French men leading the party. Biema Asabiè signed another ‘treaty of friendship’ handed over to him. Commenting on this scramble for African signatures, historian of German Togoland Peter Sebald ventures:

Considering the threatening fireweapons brandished by each and every one of these expeditions, [African rulers] sought to stay out of the clash between the colonial powers, and signed treaties with all of them. They thus demonstrated to the Europeans what little respect they granted to the treaties they had signed with others.12

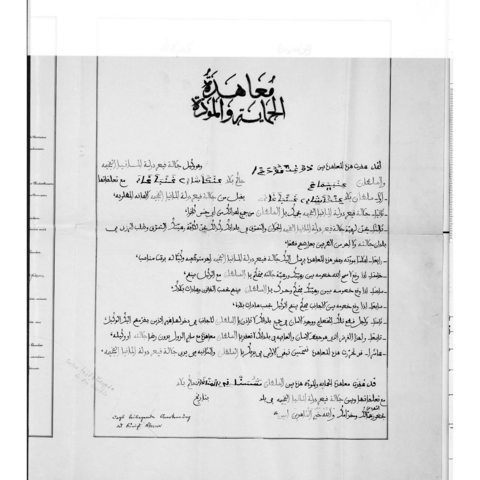

Scan der arabischsprachigen Version des sog. „Schutz- und Freundschaftsvertrags“. Bink Hallums Übersetzung des ersten Satzes ins Englischen lautet: „This treaty was agreed between Dūghita Ghūdaʿa a (Doktor Gruner?), who is the agent (wakīl) of His Highness Kaiser of the Illustrious State of Germany (dawlat Almāniyā al-fakhīma) and Sultan ʿInbaymāʿa (Nbema?), ruler of the country ʿInkuʾashiāʾī Ghanbaʾaghāʾa along with its dependencies” (Bundesarchiv R1001/3332).

Scan der arabischsprachigen Version des sog. „Schutz- und Freundschaftsvertrags“. Bink Hallums Übersetzung des ersten Satzes ins Englischen lautet: „This treaty was agreed between Dūghita Ghūdaʿa a (Doktor Gruner?), who is the agent (wakīl) of His Highness Kaiser of the Illustrious State of Germany (dawlat Almāniyā al-fakhīma) and Sultan ʿInbaymāʿa (Nbema?), ruler of the country ʿInkuʾashiāʾī Ghanbaʾaghāʾa along with its dependencies” (Bundesarchiv R1001/3332).

Gaston Thierry and the resistance of Biema Asabiè

The Germans had left one soldier stationed in the outskirts of N’Zara as a meagre proof of their commitment to protect the community from enemy incursions. Biema Asabiè witnessed a second visit from the charismatic ‘Doctor’ in late 1896. He was accompanied by two other Germans, unknown to the locals: one named Valentin von Massow, another one named Gaston Thierry. Upon their arrival on 11th December 1896, the fémè was not in town. The Germans inquired and the man from the Soma family (whom they called Daudu) told them that he was away on a military campaign.13 Biema Asabiè returned on 12th January and met Thierry for the first time, a short and flimsy man,14 born in Munich, who was recruited by the colonial department of the Foreign Office and sent to German Togoland in August 1896 after a short career in the German military. Thierry was appointed second-in-command of the Sansanné-Mango colonial station. In July 1897, the French officially recognized German colonial authority over Sansanné-Mango. But the German colonial troops faced strong resistance in the region, especially from Konkomba communities between Sansanné-Mango and Bassar. Biema Asabiè possibly started doubting the strength of German colonial rule altogether.

During his negotiations with the French in the region of Pama, Thierry saw a copy of the treaty that Biema Asabiè had signed with the French. Upon his return to the colonial station, he was therefore eager to check on the fémè’s allegiance to German rule. He barged into N’Zara with his troops in the late rainy season (17th October 1897) and summoned Biema Asabiè and other leaders to an assembly. The fémè took his time to answer Thierry’s injunctions, which probably annoyed the German lightweight. The meeting took place nine days later. Thierry’s transcript records of this meeting rather hint at a trial, a deliberate display of colonial power during which the colonialist questioned the karamò and the fémè in front of their subjects. Biema Asabiè admitted ratifying a treaty with the British and promised ‘to give the English book and banner back’ to Thierry and ‘follow the Germans’.15

He refuted Thierry’s accusation of contracting with the French: ‘I have only signed two treaties, the first with the British, the second with the Germans. All eminent members of this assembly know that and even witnessed it.’16 He admitted nevertheless having received gifts from representatives of the French colonial government. Later, Thierry summoned the karamò, whose name he spelled inconsistently, sometimes as ‘Mahamadu’, sometimes as ‘Mamadu’. He first sentenced him to a penalty payment, punishing him for vague accusations of ‘repeated offences against the colonial station in absence of a white overseer’. According to Thierry’s transcripts, the Imam swore on the Qu’ran that he had never put his name on a French treaty.17 For both the political and religious leaders in N’Zara, this must have been a humiliating performance.

Thierry apparently neither believed Biema Asabiè nor the Imam. He started fearing for his safety. Later, in his report to the governor, he wrote:

During the negotiations, the king’s headquarters behaved in such a way (beating of the royal drums, shooting of salvos, burning grass around the houses, news, and records that I received from reliable scouts), that I was compelled to summon the king again to the station on the morning of 2nd October [sic! November] for a mandatory meeting. To this he resisted and as he attempted to escape, King Nbema was shot dead.18

Four days after the murder of Biema Asabiè, members of his family, their ngyem (i.e. warriors),19 and supporters of the fémè retaliated.20 The colonial troops crushed the resistance fighters, killing at least fifteen of them. The karamò fled into exile. Thierry then ordered his soldiers to search the king’s headquarters, where they reportedly found a contract with the French. It is highly probable that it is at that moment that Thierry entered the late fémè’s headquarters for the first time. It seems highly probable that he took advantage of this search to lay hands on precious belongings of the noble family.

Aftermath of the murder of the fémè

With this murder, Thierry put an end to a Biema dynasty. According to the head of station, the leaders left in N’Zara suggested that a descendant of Na Soma become the new fémè. Thinking of himself as the paramount authority on local politics, Thierry approved the newly appointed ruler and enskinned him as ‘King Adjanda’ on 18th November 1897. The former Imam was allowed to come back from exile, but Thierry dismissed him of his functions and appointed a new religious leader. The Biema family and their supporters were forced to atone for their behaviour and Thierry distilled a series of punishing measures, the detail of which he does not render.21 It can nonetheless be reasonably assumed that both corporal punishment and confiscation of their cattle and possessions were part of those terms.

On 1st December, the chief of the police forces, Valentin von Massow, returned to Sansanné-Mango. He found the town in a dire state. The northern part had been deserted. Many of Biema Asabiè’s supporters had fled, no less than half of Sansanné-Mango’s population according to Massow.22 Thierry, however, was in the best of health and had newly been appointed as the head of station in Sansanné-Mango by the colonial government. He organised a public demonstration of German firepower, a means of deterrence addressed to anyone still doubting his power. On 7th December, his troops fired the Maxim-gun in the middle of the town. According to Massow, attendees were ‘amazed, astonished and also frightened’.23 This statement seriously questions Thierry’s statement that members of the Soma estate had supported his exactions against Biema Asabiè, the Imam and their fellow Anufôm. Rather, these observations hint at a reign of terror in the immediate aftermath of the murder of the fémè.

In August 1899, exactly three years after his arrival on the African continent, Thierry left the colony for his first home leave. On his journey, he was accompanied by forty-six crates that contained objects listed as the former belongings of ruling families in Sansanné-Mango, including a non-negligible number of items made of gold and silver. Thierry was well-aware that German museums would be interested in these objects: his assistant Lieutenant Brütsch had indeed already sold items from German Togoland to the Linden-Museum in Stuttgart less than a year before. Thierry was eager to poke the interest of anthropologists and sell objects that, to them, would appear unique and new in their museum collections. Upon his arrival in Berlin, he called on the assistant director of the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde, Felix von Luschan.

From 30,000 to 5,000 marks

In their conversation, Thierry estimated his collection to be worth 30,000 marks.24 After Luschan deprecated this price, Thierry reconsidered and offered it for a bracket of six to eight thousand marks. Luschan inquired in the museum’s budget and, in October, wrote to the officer that the museum could not raise such a sum. Anyway, they were only interested in purchasing about 250 items. Besides, considering the large amount of doubles of the same kind, Luschan argued, Thierry’s collection should also be offered to other museums.25 In November, the lieutenant therefore contacted the director of the museum in Stuttgart, Karl von Linden, in which he repeated that his collection was worth 30,000 marks.26 Little did he know that Luschan and Linden had already discussed the matter with one another, Luschan arguing that Thierry’s first offer was ‘absurd’ and his second offer dishonest: ‘he obviously makes profit out of it and I condemn this, especially since he was on official mission over there, as an officer of the Empire, not for private matter’.27 After several letters from Luschan, Thierry was compelled to lower his price and made his last offer in January: ‘to cover a share of [his] cash expenses’, he would not accept less than 5,000 marks in total.28 Luschan suggested he would pick out three hundred items for his museum in Berlin; if Stuttgart could raise such a sum, it would then receive the remaining 1,400 items.

Distribution among three: Berlin, Stuttgart und Leipzig

Karl von Linden could rely on a network of influential people interested in colonial affairs and eager to invest in the cultural and scientific sector. The entrepreneur, museum patron and art collector Ernst Sieglin was willing to help the museum’s financial body to acquire Thierry’s collection. Sieglin maintained he could raise up to 2,500 marks. This generous support granted him the status of ‘collector’ in the database of the Linden-Museum. Stuttgart would then purchase around seven hundred items for 2,500 mark, in Luschan’s words, ‘the bigger and better half of his collection’.29 In reality, Berlin had the better deal thanks to its privileged position as the collection’s caretaker. Half of Thierry’s price was covered, but Luschan was not eager to spend money from the Berlin museum’s budget. This is when he turned to his former colleague Karl Weule, director of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Leipzig.

Weule was interested in purchasing the rest of the collection. Thierry haggled with Weule with Luschan as an intermediary. The negotiations started at 2,500, dropped to 1,800 marks and landed at 1,500 marks. In the end, Berlin covered the transportation costs (roughly 370 mark)

and got about three hundred items.30 Stuttgart paid 2,500 marks for seven hundred items, including several of the precious gold and silver artefacts. Leipzig received three hundred items in exchange for 1,500 marks. Altogether, Thierry therefore effectively received 4,000 marks for his collection, transferred to him in February 1900. According to studies in the history of currencies, this sum would amount to approximately €30,000 of purchasing power nowadays.31

Belongings from N’Zara at the Grassi Museum

Weule and his museum were obviously the third wheel in the transaction. Luschan and Linden divided among themselves the prominent gold and silver objects and many of the other items clearly described as having belonged to leaders or noble estates of N’Zara ended up in Berlin or Stuttgart: among them, a golden ‘amulet’ that reportedly hung on Biema Asabiè’s neck (8399 in Stuttgart), finger rings that reportedly belonged to ‘King † Nbema’ (III C 10916 & III C 10919 in Berlin) and two from ‘Mohamma, former Imam of Sansanné-Mango’ (III C 10917 in Berlin and 8398 in Stuttgart). Still, the silk brocade and the garments from Sansanné-Mango in the collection in Leipzig reveal Thierry’s knowledge about some of the people he collected on, including possibly resistance fighters from Biema Asabiè’s supporters.

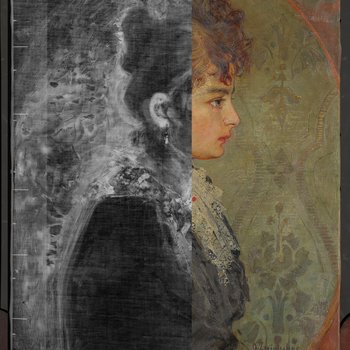

Hemd mit Goldbrokat

© SKD, Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen, Foto: Julia Pfau

In Thierry’s detailed list, the silk brocade is described as followed:

A royal robe of the Kaddārā family in Mangu, close relatives of the first royal family of Diamarbu, who also immigrated from the area of Anu [...]. The eldest son of an ancestor called Muhama received the robe after emigrating (therefore bought some 300 years ago from a Haussa trader for forty-one slaves (?)) as a gift for special bravery in a campaign against Kussáka or Kántindí led by the Mangu King Nbema, first king in the Chakosi region. Witness the Arabic work, as well as the quite different breast pockets that were anyhow subsequently added for the purpose of sale in Sudan.32

Thierry thereby maintains that this item of clothing had been passed on from generation to generation from the rule of Na Bièma Bonsafô up to Biema Asabiè. Even though the veracity of this information is questionable, oral history compiled by Emile and Els van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal, based on the knowledge of Imam Al-Hadji Sani Abdulaye, both supports and challenges Thierry’s claims. The two anthropologists wrote that “Nana Mama, the leader of the important donzo Badara patrilineage, was a maternal uncle of Na Byema (maternal uncle: ngwe).”33 If this family were close relatives of the Bièma, then Thierry probably mispelt “Kaddārā” for what the van Rouveroy van Nieuwaals called “Badara.” A member of the Bièma patrilineage might have therefore received the brocade from a member of the Badara. If Thierry’s detail on the price of this gown is to be believed, it seems even plausible that this royal brocade had belonged to Bièma Bonsafô himself.

Continuing with Thierry’s descriptions of the Anufo warriors’ garments in the custody of the Grassi museum, he wrote that each one of them had cost 200,000 to 400,000 cowries before the arrival of Europeans (according to him 200 to 300 marks). His notes further inform that the war outfits lost their original worth since they seemed to offer no protection against European bullets.34 Before Thierry’s troops killed Biema Asabiè, the Anufôm had in fact not yet fought against European weaponry. Although they might have known from testimonies of their neighbours – the kingdom of Dagbon and Konkomba settlements – that their outfits could not protect them from the bullets of the Maxim-gun, the people of N’Zara had to witness it first-hand after Thierry’s violent reaction to Biema Asabiè’s resistance. These garments and the history of their alleged loss of value are thus closely interwoven with the history of military and colonial conquest of the region.

Making profit from war booty

Twelve months after selling his collection, Thierry was dismissed from his position in northern Togoland. The governor at the time, August Köhler, explicitly criticized Thierry’s disregard for financial reports on the expenses of his station. In a pamphlet against the officer addressed to the Colonial Department of the Foreign Office, Köhler added:

‘[Thierry’s] main activity consisted in leading the life of a Landknecht [mercenary soldiers in the early modern era], repeatedly absconding from the station for many months without reporting to the government, and undertaking one punitive expedition after another, always resulting in abundant spoils of war which provided the basis for his business’.35

Thierry does not give any precision on the conditions of acquisition of these objects. But this statement by the governor suffices to recognize that a large portion of Thierry’s collection, if not proved otherwise, was pure and simple spoils of war, including from the violent repression in Sansanné-Mango.

Accompanying the list that describes these precious objects is an interesting nota bene drafted by Thierry that reads:

Many of those golden artefacts from Mangu, including the swords (as well as silver that belonged to the Imam and other royal families) were imported by the current regents of Djakossi (Anufo) from their former hometown, Anu, in the Gold Coast. There were hence forged at least three and a half centuries ago by the Ashanti, since, ever since this exodus, there has been no contact whatsoever between the people of Mangu and their original hometown, Anu.36

If we are to believe the colonial officer and the authentic character of these belongings, it seems hardly thinkable that the noble families of N’Zara would depart from such precious artefacts willingly, let alone exchange them as gifts. They were therefore probably plundered by the lieutenant or acquired under duress thanks to his status as the head of the colonial station. In addition, this statement reveals Thierry’s relative ignorance of the history of the Anufôm, Ano being situated in today’s Ivory Coast. Finally, Thierry’s lure of profit highly questions the truthfulness of his notes: the officer might indeed have attributed royal characteristics to artefacts that were not seen as such by the local population to raise the scientific – and therefore pecuniary – worth of his booty.

August Köhler and Felix von Luschan both assumed that Thierry’s financial situation was close to bankruptcy.37 However, Thierry’s marketing tactics for selling his possessions were consistent and might just as well be interpreted as cunning opportunistic behaviour. Up until his dismissal, he indeed consistently sought to cash in on his position as head of a colonial station. He made profit by selling horses he had seized from local communities to his fellow colonialists.38 He also proudly showcased his war booty. When the governor paid him a visit in March 1899, Thierry allegedly wore local garments instead of colonial attire.39 A few weeks later, he boasted with his spoils in front of Valentin von Massow.40 A few months later, before boarding a ship for home leave, Thierry took a moment to pose in front of the camera. This is the only photograph of him that could be found until today. The grainy shot, published in the Deutsche Kolonialzeitung in early January 1900, shows him in Hausa clothing, wearing a turban, propped up with a sword that sustains his confident pose.41 Museum staff were avid readers of colonial press at the time. With hindsight, this image might have served as surreptitious advertisement, comforting Karl von Linden in Stuttgart and Karl Weule in Leipzig in their decision to purchase parts of Thierry’s collection, which they did less than a month later.

Colonial mindsets and representations, as well as institutional racism on a global scale, are still omnipresent today. Histories like this one show again that museums such as the Linden-Museum were not exempt of responsibility in the violent establishment and upholding of racist structures. A genuine reparation of that wrong is impossible.

Nevertheless, museums must act. First, institutions involved in this brutal history of dispossession need to live up to their responsibility and proactively seek dialogue with Togolese researchers, authorities, and civil society. Secondly, the archives, databases and storerooms of the Berlin, Stuttgart and Leipzig museums must be made open and accessible to interested parties, including those located remotely. Thirdly, it would be desirable to witness these institutions adopt a clear position vis-à-vis their own history by genuinely apologising for the expropriation of West African societies, in this case, to the Republic of Togo and the political and cultural elite in Sansanné-Mango. Finally, they should offer the possibility of an unconditional return of these valuable Anufôm artefacts to Togo.

Last but not least, Thierry did not only grab material heritage. More than sixty ancestral remains from northern Togo dug up by Thierry are indeed in the custody of the Foundation Prussian Cultural Heritage. It is high time the stories behind the presence of these ancestors and these belongings in German museums be told alongside ethical processes of atonement for the wrongs of the past.

1 MAf 01136.

2 MAf 1150, MAf 1152, MAf 1156, MAf 1158, MAf 1160.

3 Receipt W. Homann & Co., 10 Aug. 1899, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, p. 231.

4 For the different accounts, see Seefried, p. 423; van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal & van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal-Baerends, pp. 16–18; Gayibor, Histoire des Togolais, Tome 1, pp. 123–124; Tcham, p. 57; Kozi, pp. 6–8.

5 See van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal & van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal-Baerends, p. 15–17

6 His name has been spelt ‘Bema-Sabie’, ‘Nbema’ or occasionally ‘Mbema’ in German colonial literature. Graham Norris and Heine spelt it ‘Biema Asabi’ and Nicoué Gayibor uses ‘Biema Asabiè’, which I chose to render here (Histoire des Togolais, Tome 1, p. 124). The name of the donzo from which he originated has been also inconsistently rendered as ‘Djamarbu’ or ‘Djeremabu’ in colonial archives (see Seefried, p. 424). For a detailed discussion of the title of fémè and the genealogy of rulers in N’Zara, see Graham Norris & Heine, pp. 120–124; Gayibor, Histoire des Togolais, Tome 1, pp. 123–125.

7 Ernst von Carnap-Quernheimb.

8 Freiherr Adolf von Seefried auf Buttenheim published an article on the history of Sansanné-Mango almost two decades later in the journal of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory (BGAEU). In this article, he sums up and criticizes former publications on local history and cultures by his fellow colonialists Julius von Zech and Gaston Thierry. See Seefried, pp. 421–435.

9 At the time, most of the elite of N’Zara did not know the Latin alphabet, but they could read and write Arabic.

10 Itandala, p. 7.

11 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Jeder Vertrag ist nur Papier und bedeutet nur das, was die betreffende Diplomatie daraus macht, darum kümmere ich mich nicht um Verträge, die Ferguson geschlossen hat.’ (Gruner to Danckelmann, 13 Jan. 1895, German Federal Archives, R1001/3330, p. 99).

12 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Angesichts der drohenden Waffen der einzelnen Expeditionen suchten diese, sich aus dem Streit der Kolonialmächte herauszuhalten, und schlössen mit allen Verträge ab, demonstrierten doch die Europäer selbst, wie wenig sie mit anderen abgeschlossene Verträge respektierten’ (Sebald, p. 166).

13 Massow, p. 208.

14 According to his contemporary Valentin von Massow, Thierry weighed no more than 110 pounds, roughly fifty kilograms (Massow, p. 766).

15 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Ich habe früher versprochen das englische Buch zurückzugeben. Ich will dir jetzt das englischen Buch und die Flagge geben, denn ich weiß, daß ich bloß dem Deutschen folgen kann’ (Transcript records of 26 Oct. 1897, German Federal Archives, R1001/4392, p. 169).

16 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Ich habe nur zweimal einen Vertrag unterzeichnet, den ersten mit dem Engländer, den zweiten mit dem Deutschen. Alle Großen hier wissen dies so und haben es gesehen’ (ibid).

17 Transcript records of 26 Oct. 1897, German Federal Archives, R1001/4392, p. 170.

18 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Gleichzeitig war die Haltung des Königviertels eine derartige (Schlagen der Königstrommeln, Abfeuern von Gewehren, Abbrennen des Grases um die Häuser, mir durch sicheren Kundschafter zugegangene Redereien und Aufsetzungen), daß ich genötigt war, den König am 2. Oktober [sic! November] a.c. zwangsweise zu mir zu beordern. Bei dem von ihm dabei geleisteten Widerstand resp. Fluchtversuch ist König Nbema erschossen worden. Bei dem bewaffneten Vorgehen der Königspartei sind meinerseits etwa 20 Eingeborene erschossen worden; ich bemerke ausdrücklich, daß die gesammte deutschfreundliche Partei sich in keiner Weise dem Widerstand angeschlossen hat.’ (Report by Thierry, 19 Nov. 1897, German Federal Archives, R1001/4392, p. 163; underscore in the original).

19 Van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal & van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal-Baerends, p. 17.

20 Gayibor, Histoire des Togolais, Tome 3, p. 243.

21 Report by Thierry, 19 Nov. 1897, German Federal Archives, R1001/4392, pp. 166–167.

22 Massow, p. 488.

23 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘[D]ie Sache […] rief großes Erstaunen, Verwunderung und auch Furcht hervor’ (Massow, p. 492).

24 Luschan to Linden, 16 Nov. 1899, Korrespondenzakte Thierry, Archives of the Linden-Museum Stuttgart.

25 Luschan to Thierry, 6 Oct. 1899, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, p. 232.

26 Thierry to Linden, undated (received 14 Nov. 1899), Korrespondenzakte Thierry, Archives of the Linden-Museum Stuttgart.

27 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘[M]it anderen Worten, er war damals bereit, seine Sammlung tel quel für 6-8000 M. zu verkaufen. Auch das ist noch ein reichlich hoher Preis, bei dem er sicher Gewinn hat, was ich eigentlich nicht correct finde, da er nicht als Privatmann sondern als Kaiserlicher Offizier drüben war’ (Luschan to Linden, 14 Nov. 1899, Korrespondenzakte Thierry, Archives of the Linden-Museum Stuttgart). Felicitas Bergner summed up the political decision that gave the Berlin museum ownership of colonial collections as such: “Durch einen Bundesratsbeschluss vom 21. Februar 1889 dem [Berliner] Museum das Eigentumsrecht an allen Sammlungen aus den Deutschen Schutzgebieten zugestanden, die auf mit Reichsmitteln finanzierten Expeditionen erworben wurden. 1891 wurde die Abgabepflicht nach Berlin auf die in den Deutschen Schutzgebieten tätigen Beamten und 1896 zusätzlich auf Schutztruppen-angehörige ausgeweitet.” (Bergner, p. 228).

28 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘[Z]ur Deckung eines Teiles meiner Baar-Ankosten im Sinne genannten Schreibens durch Vermittlung des Kgl. Museums die Summe von fünftausend Mark (5000 Mk) erlöst wird’ (Thierry to Luschan, 12 Jan. 1900, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, p. 277).

29 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Volle drei Stunden haben wir verhandelt und ich kann Ihnen nun als Ergebnis mittheilen, dass Th. bereit ist, Ihnen die grössere und bessere Hälfte seiner Sammlung, rund 600 Stücke (aber keine Gold und Silber Sachen) um 2.500 M. zur Verfügung zu stellen’ (Luschan to Linden, 3 Feb. 1900, Korrespondenzakte Thierry, Archives of the Linden-Museum Stuttgart).

30 The exact price of the transportation costs from Lomé to Hamburg was 344,60 marks, from Hamburg to Berlin 22,80 marks (Notes by Junker, 14 Aug. 1899, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, p. 231).

31 According to a study by the German Federal Bank, 1 Mark in 1900 was roughly equal to 7,20 Euros in 2021 (see Deutsche Bundesbank, ‘Kaufkraftäquivalente historischer Beträge in deutschen Währungen’, 24 Jan. 2021, Bundesbank.de. Web 2 Aug. 2022. https://www.bundesbank.de/de/statistiken/konjunktur-und-preise/-/kaufkraftaequivalente-historischer-betraege-in-deutschen-waehrungen-615162).

32 “Ein königliches Gewand der Familie Kattārā Kaddārā in Mangu, welche als nahe Verwandte der 1. Königsfamilie der Diamarbu ebenfalls aus der Gegend von Anu auch Chakosi eingewandert sind. Der älteste Sohn des Ahnen Muhama kaufte kurz bekam nach der Einwanderung (von einem Haussa-Händler für 41 Sklaven dies Gewand, also vor etwas 300 Jahren (?) gekauft) das Gewand als ein Geschenk für besondere Tapferkeit in einem Feldzuge gegen Kussáka oder Kántindí von dem Mangu Kg. Nbema, dem ersten Kg. in Chakosi. Siehe die arabische Arbeit, sowie die ganz verschiedene, jedenfalls nachträglich zwecks Verkauf nach Sudan aufgesetzte Brusttasche p.p.” (Thierry, Notes on his collection, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, 271–272).

33 Van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal & van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal-Baerends, p. 17.

34 Thierry, Notes on collection, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, pp. 265–266.

35 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Seine Haupttätigkeit bestand in der Führung einer Art Landknechtsleben, indem er sich wiederholt ohne Anzeige an das Gouvernement, auf viele Monate vor der Station entfernte, und eine Strafexpedition nach der anderen unternahm, deren Ergebnis stets reiche Kriegsbeute – die Grundlage seiner Finanzwirtschaft – war’ (Letter from Köhler, Notes to K.A. 1035, 22 Feb. 1901, German Federal Archives, R1001/4393, p. 160).

36 Original in German, translation by the author: ‘Sämmtliche aus Mangu stammenden Goldgegestände, einschl. der Schwerter (sowie auch Silberungen des Imam’s und Königsfamilien) sind von der heute in Djakossi herrschenden Mangu-Bevölkerung (Anufo) aus ihrer alten Heimat in der Goldküste Anu bei ihrer Auswanderung von dorther mitgebracht worden, demnach mindestens vor 3 ½ Jahrhundert aus Ashanti-Goldgearbeitet, da noch der Auswanderung keine Verbindung zwischen Mangu-Volk und ursprünglichen Heimat Anu existierte.’ (Thierry, Gaston, Notes on his collection, Archives of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, I/MV 721, E 803/1899, pp. 259–260).

37 See Sebald, p. 197; Letter from Luschan to Linden, 16 Nov. 1899, Korrespondenzakte Thierry, Archives of the Linden-Museum Stuttgart.

38 See Massow, p. 491, 495.

39 See Massow, p. 783.

40 See Massow, p. 799.

41 Bauer, Heinrich (1990), “Pioniere der deutschen Kolonialpolitik,” Deutsche Kolonialzeitung, Vol. 17, N° 2, 11 Jan. 1900, p. 15.

Works cited

Bauer, Heinrich. (1900, 11 Jan. 1900). Pioniere der deutschen Kolonialpolitik. Deutsche Kolonialzeitung, 17, 15-16.

Bergner, Felicitas (1996): Ethnographisches Sammeln in Afrika während der deutschen Kolonialzeit. Ein Beitrag zur Sammlungsgeschichte deutscher Völkerkundemuseen. In: Paideuma, 42, S. 225-235.

Gayibor, Nicoué (2011a): Histoire des Togolais, Tome 1: De l'Histoire des Origines à l'Histoire du Peuplement. Paris: Editions KARTHALA.

Gayibor, Nicoué (2011b): Histoire des Togolais, Tome 3: Des origines aux années 1960 - Le Togo sous administration coloniale. Lomé & Paris: Karthala et Presses Universitaires de Lomé.

Graham Norris, Edward, & Peter Heine (1982): Genealogical Manipulations and Social Identity in Sansanne Mango, Northern Togo: an "imām"-List and the Qasīda" of ar-Ra'īs Bādīs. In: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 45(1), S. 118-137.

Itandala, Buluda (1992): African Response to German Colonialism in East Africa: The Case of Usukuma, 1890-1918. In: Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 20(1).

Kozi, Bonson Marie Laure (2013): Description comparative des langues du sous-groupe Bia Nord: agni, baule, anufo. Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies. Bayreuth: Universität Bayreuth.

Sebald, Peter (1988): Togo 1884-1914: eine Geschichte der deutschen 'Musterkolonie' auf der Grundlage amtlicher Quellen. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Tcham, Badjow K. (2007): Le royaume Anoufo de Sansanné-Mango : de 1800 à 1897. Lomé: Presses de l'Université de Lomé.

van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal, Emile A.B., & Els A. van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal-Baerends (1986): Muslims in Mango (Northern Togo). Some aspects: Writing and Prayer. Leiden, Netherlands: African Studies Centre.

von Massow, Valentin (2014): Die Eroberung von Nordtogo 1896 - 1899: Tagebücher und Briefe. Bremen: Edition Falkenberg.

von Seefried, Freiherrn (1913): Beiträge zur Geschichte des Manguvolkes in Togo. In: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 45(3), S. 421-435.

Also of interest:

The empire, the kingdom, the city and the people that produced those exquisite Bronzes, carved ivories and wood works, clay and iron sculptures are not in oblivion, but subject of ongoing restitution and repatriation requests. Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie on the history of a questionable collection and the efforts for its repatriation.

How is what we commonly call "global" being shaped, and what part do museums actually play in this process? The term "worlding" is used to describe the ongoing formation and reshaping of the global as a multi-perspective process in which a wide variety of regional positions are involved. This summer, a conference titled "Worlding Public Cultures: The Arts and Social Innovation (WPC)" took place at the Japanisches Palais, which dealt with the museum contributions to the globalization process as understood according to this concept.

Seventeen works from the artist’s oeuvre – which originally comprised around 150 paintings – were examined in the research project “Oskar Zwintscher (1870–1916). The Unknown Masterpiece” by the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in the Albertinum, funded by the Friede Springer Stiftung, subjecting them to art technology analysis in the painting restoration workshop. Here you can gain insight into the complexity found in the structure of Oskar Zwintscher’s paintings.