An old life must end for a new life to begin. For that reason, life on our planet has been closely linked to death and illness from the very beginning, and disease has been humanity’s constant companion for millennia. Especially after human beings began to settle in one place, developing agriculture and practising animal husbandry, and thus living in larger communities and coming into contact with animals, diseases are likely not only to have been an everyday occurrence, but also to have led to epidemics. The new lifestyle meant that infectious diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and other pathogens could easily be transmitted from animals to humans and vice versa (zoonotic diseases).

Unlike more recent history, which is documented in written records, works of art and so on, research into diseases and epidemics in the early, preliterate days of human history relies almost entirely on material evidence and particularly human or animal remains. For some time now, it has been possible to identify some diseases, or signs of deficiency and wear, in skeletal remains using microscopy, x-rays or computer tomography. In recent years it has also become possible to identify infectious diseases using genetic analysis.

So far, investigations into skeletons in Saxony dating back to the third millennium BC have mainly revealed degenerative conditions, signs of deficiency and other diseases. One study (Teegen 2011), for instance, examined human remains from the Bell Beaker culture (see below) in the Leipzig area. It revealed developmental tooth disorders (dental enamel and root hypoplasia) and growth arrest lines (Harris lines) in the long bones, along with Vitamin C deficiency (childhood scurvy), a sign of indefinite periods of childhood stress and deficiency. Bony growths (some porous), fractures and vascular impressions on certain parts of the skull were probably an indication of inflammatory processes. In several adults, changes in the bones also pointed to chronic sinusitis. In the case of one woman, aged at most 25 years old and buried between 2469 and 2299 BC in a Corded Ware grave (see below) in the Leipzig district near Greitschütz, the skull was so degraded that it was paper-thin in places, and fine porotic lesions were found. Although it cannot be said with total certainty whether the changes were due to anaemia, inflammation or a tumour, whatever caused them is sure to have been fatal (Dalidowski 2003).

Carl Teumer/Alexander Rötzsch: Die Pest aus "Das Puppenspiel vom Dr. Faust", 1947

© Puppentheatersammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The maxillary lateral incisors in the skull of a man also excavated near Großstorkwitz showed signs of an abscess (red arrow) at the tip of the root that considerably enlarged the pulp chamber and even caused an opening to appear leading into the nasal cavity (Conrad & Teegen 2009). According to carbon-14 dating, the man was buried between 2575 and 2473 BC.

© Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office. Taken by Jürgen Lösel

In prehistoric times, inflammatory dental diseases, mainly caused by tooth decay or tartar, were very common. Unlike today, they could be so severe that they extended far into the jawbone and could even lead to death. In some circumstances, abscesses at the tip of a tooth’s root could progress to create a channel leading into the nasal cavity, causing persistent pain and inflammation. In addition, non-natural causes of death have been found, such as head trauma resulting from blows with stone axes, or bones penetrated by arrowheads (Haak et al. 2008; Conrad & Teegen 2009).

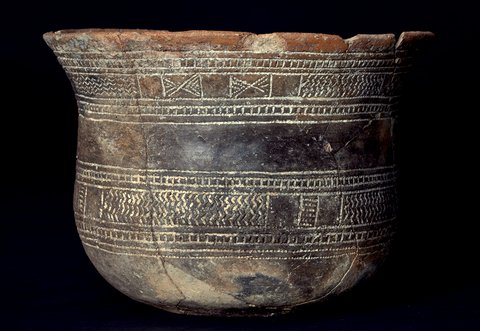

The Corded Ware culture is named after the practice of pressing twisted cords into the wet clay prior to firing pottery, as with the vessel from Greitschütz, in the Leipzig district. This well-preserved beaker was found alongside other pottery in the grave of a roughly 13-year-old youth who appears to have been female. According to carbon-14 dating, she was buried between 2574 and 2457 BC. The burial site, uncovered in 1998 by the Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office, holds 24 graves, making it the largest of its kind in Saxony from that time.

© Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office. Taken by Jürgen Lösel

These examples show clearly that even in the third millennium BC, i.e. between 3000 and 2000 BC, human beings must have been constantly beset by disease. At the time, social and cultural developments in Mesopotamia and on the Nile and Indus were reaching their first peak; complex state structures were developing hand in hand with the construction of large towns and the use of writing. In Central Europe, the same period was characterised by processes of continual change extending from the Neolithic Age, when agriculture and animal husbandry began to be established, to the Bronze Age. While the archaeological groups of the fourth millennium BC tended to be restricted to specific regions, the third millennium BC featured two large-scale archaeological complexes. The Corded Ware culture (c. 2750–2200 BC) fanned out from various points extending from Ukraine to Switzerland, while the slightly later Bell Beaker culture (c. 2500–2150 BC) stretched from Portugal to Poland, also with various centres.

The Bell Beaker culture is named after its bell-shaped vessels such as this one from Kölsa, in the North Saxony district. It comes from the grave of a woman who was exceptionally old for the period, at 48 to 69 years of age (https://archaeo3d.de/sachsen/2019-04-24_fi_0002/) and, according to carbon-14 dating, was buried between 2402 and 2200 BC. Both bones in her lower forearm showed signs of a healed “nightstick” fracture that may have come from warding off a blow or a similar defensive action.

© Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office. Taken by Ursula Wohmann

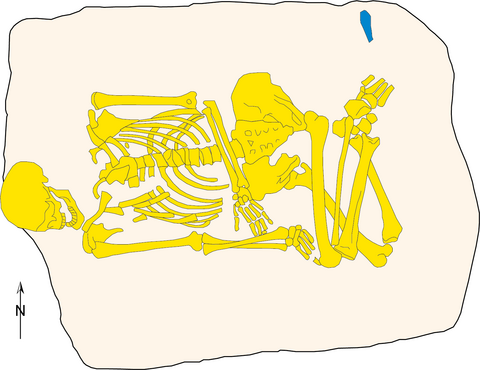

Apart from the use of beakers, another factor uniting the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures was their burial rites, both revolving around gendered burial practices that mirrored one another exactly. As a rule, the dead were buried on their side in a crouched position. In the Corded Ware culture, men usually lay on their right side and women on their left side, whereas women from the Bell Beaker culture were placed on their right side and the men on their left side. The rise of this burial practice at the start of the third millennium BC is linked to a series of graves that already show signs of this gendered positioning but do not yet contain any pottery from the Corded Ware culture.

Analysis of the genetic material of this man excavated near Großstorkwitz, laid out on his left-hand side, revealed the presence of the plague pathogen, among other things. This and a similarly ancient grave from Bohemia are the oldest evidence to date of this potentially deadly disease being in Central Europe. The only item buried with him was a flint (blue).

© Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office

One such gravesite was excavated in 1998 to the south of Großstorkwitz, a district roughly 18 km to the south of Leipzig, by the Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office (LfA) in the lead-up to a utility conduit being laid. Carbon-14 dating quickly showed that the man, aged between 35 and 45, died between 2848 and 2572 BC. He was buried on his right-hand side lying from west to east and facing south, in the manner typical of Corded Ware graves. The only item buried with him was a flint blade. Graves from this early part of the third millennium BC are themselves a rarity in Saxony, but that was not all. An analysis of the man’s teeth, carried out in 2020 at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, revealed a particular surprise. Traces of the genetic material (DNA) of Yersinia pestis were found inside his bottom right-hand molar (Andrades Valtueña et al. 2022). This bacterium causes the disease we famously now know as the plague, though it cannot be said for sure whether the man actually died of the plague.

This flint blade, measuring 8.4 cm in length, was buried some 4800 years ago alongside the man from Großstorkwitz whose DNA analysis revealed the presence of the plague pathogen. As it was placed near the man’s feet, he does not seem to have been carrying it on his person at the time of the burial. Blades of this kind were common grave goods of the period.

© Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office. Taken by Matthias Conrad

A similarly ancient case of the plague is known from the Bohemian village of Vliněves, in the Czech Republic to the north of Prague. This, too, is a 40- to 60-year-old man, who was given a right-facing crouched inhumation between roughly 2885 and 2663 BC, buried with flint blades. The two cases fit remarkably well into a series of other, similarly ancient cases of the plague known from south-east Europe (Rascovan et al. 2019), the North Caucasian steppe, southern Siberia and Lake Baikal. They fit not only into the timeline and geography but also in terms of phylogenetics (the study of species’ evolution and their relationship to other groups of organisms). Although further evidence has been found locating the plague in Central Europe in the third millennium BC, such cases are as yet isolated, making it hard to judge how seriously the disease affected communities at that time.

Interestingly, the man from Großstorkwitz has a far higher number of Steppe-related genes compared with both earlier pastoralist groups from the fourth millennium BC and those buried slightly later with Corded Ware vessels. His characteristic genetic signature thus indicates that his ancestors probably came from the eastern Steppe region, or that occupied by the Yamnaya culture, some four or five generations before. The Yamnaya culture includes various groups of nomadic peoples in the area from the north of the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea, who largely lived from livestock farming and herding. Interestingly, the culture already features the key characteristics of the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures found in Europe: single graves and the ideal of the warrior. Research is being carried out into exactly what form these migratory movements from the eastern steppes took (e.g. Haak et al. 2015; Allentoft et al. 2015; Kaiser 2021). They are said to have been triggered in part by the rise of the first states in Mesopotamia and the associated establishment of a regime of power to which neighbouring societies were also subjected (Furholt 2021).

Since even older evidence of the plague has been found, dating to the end of the fourth millennium BC (Rascovan et al. 2019; Susat et al. 2021), the theory can be ruled out that migrants from the Eurasian steppes brought the plague to Central Europe in the third millennium BC (Trautmann 2021). The period at the end of the fourth and the start of the third millennium BC is thus a stage in the past that was characterised by an exceptionally high level of human mobility. Technological and cultural innovations, genes and indeed diseases accompanied the people on their travels.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Harald Stäuble of the Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office (LfA) for providing the carbon-14 data on the graves in Großstorkwitz, Greitschütz and Kölsa.

Also of interest:

What we can learn from coins and medals goes far beyond discovering hidden hoards or studying the economic consequences of events. Such artefacts also tell us about societies’ beliefs, hopes and fears. Currently, an exhibition at the Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection) is devoted to the connection between coins and epidemics. Curator Ilka Hagen explains here what one has to do with the other.

![[Translate to English:] Asklepios and Telesphoros [Translate to English:] Bronze medal, the relief of which shows the holy Asclepius. On the right he holds a large, almost club-like staff towards the ground, with the snake coiling around it (Asclepius' or Asclepius' staff), in front of his left stands the small Telesphoros with hood and cape. The inscription reads: "ECOLES DE MEDECINE".](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/c/csm_1a_502b95e988.jpg)

In the storerooms of the Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde in Leipzig lie half a dozen of belongings of the former rulers of Sansanné-Mango, a town in northern Togo. how did they come to Leipzig? What was the role of the museum's former director, Karl Weule, in the translocation of this royal heritage? Can similar items be found in Berlin or elsewhere?

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/d/csm_Abb_4_quad_ba849ed3ea.png)

Part 3 of MeissenLab is about trade with countries outside the socialist bloc. The most important sales market was West Germany. In the 1980s, Japan also rose to a prominent position, with the GDR maintaining close diplomatic and economic ties.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/8/csm_Meissenlabs_-Making_of.mp4-00005_835eb675a5.jpg)

Allentoft et al. 2015: M. E. Allentoft/M. Sikora/K.-G Sjögren/S. Rasmussen/M. Rasmussen/J. Stenderup/P. B. Damgaard/H. Schroeder/T. Ahlström/L. Vinner/A.-S. Malaspinas/A. Margaryan/T. Higham/D. Chivall/N. Lynnerup/L. Harvig/J. Baron/P. Della Casa/P. Dabrowski/P. R. Duffy/A. V. Ebel/A. Epimakhov/K. Frei/M.Furmanek/T. Gralak/A. Gromov/S. Gronkiewicz/G. Gruppe/T. Hajdu/R. Jarysz/V. Khartanovich/A. Khokhlov/V. Kiss/J. Kolár/A. Kriiska/I. Lasak/C. Longhi/G. McGlynn/A. Merkevicius/I. Merkyte/M. Metspalu/R. Mkrtchyan/V. Moiseyev/L. Paja/G. Pálfi/D. Pokutta/Ł. Pospieszny/T. D. Price/L. Saag/M. Sablin/N. Shishlina/V. Smrcka/V. I. Soenov/V. Szeverényi/G. Tóth/S. V. Trifanova/L. Varul/M. Vicze/L. Yepiskoposyan/V. Zhitenev/L. Orlando/T. Sicheritz-Pontén/S. Brunak/R. Nielsen/K. Kristiansen/E. Willerslev, Population Genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522, 2015, 167–172.

Andrades Valtueña et al. 2022: A. Andrades Valtueña/G. U. Neumann/M. A. Spyroua/L. Musralina/F. Aron/A. Beisenov/A. B. Belinskiy/K. I. Bosa/A. Buzhilovai/M. Conrad/L. B. Djansugurova/M. Dobeš/M. Ernée/J. Fernández-Eraso/B. Frohlich/M. Furmanek/A. Hałuszko/S. Hansen/É. Harney/A. N. Hiss/A. Hübner/F. M. Key/E. Khussainova/E. Kitov/A. O. Kitova/C. Knipper/D. Kühnert/C. Lalueza-Fox/J. Littleton/K. Massy/A. Mittnik/J. A. Mujika-Alustiza/I. Olalde/L. Papac/S. Penske/J. Peška/R. Pinhasi/D. Reich/S. Reinhold/R. Stahl/H. Stäuble/R. I. Tukhbatova/S. Vasilyev/E. Veselovskaya/C. Warinner/P. W. Stockhammer/W. Haak/J. Krause/A. Herbig, Stone Age Yersinia pestis genomes shed light on the early evolution, diversity, and ecology of plague. PNAS 119, H. 17, 2022, 1–11.

[DOI]

Conrad/Teegen 2009: M. Conrad/W.-R. Teegen, Gewalt und Konfliktaustragung im 3. Jahrtausend v. Chr. archæo 6, 2009, 48–53.

Dalidowski 2003: X. Dalidowski, Die Skelettgräber und Gruben mit menschlichen Überresten der JAGAL-Trasse in Sachsen. Unpubl. Magisterarbeit Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena (2003).

Furholt 2021: M. Furholt, Resisting the ʻviolence-inquality comlexʼ – A new model for the third millennium BC mobility in Europe. In: V. Heyd/G. Kulcsár/B. Preda-Bălănică (Hrsg.), Yamnaya Interactions. Proceedings of the International Workshop held in Helsinki, 25–26 April 2019. The Yamnaya Impact on Prehistoric Europe 2. Archaeoligua 44 (Budapest 2021) 57–81.

Haak et al. 2008: W. Haak/G. Brandt/H. N. de Jong/C. Meyer/R. Ganslmeier/V. Heyd/C. Hawkesworth/A. W. G. Pike/H. Meller/K. W. Alt, Ancient DNA, Strontium isotopes, and osteological analyses shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age. PNAS 105 (47), 2008, 18226–18231. [DOI]

Haak et al. 2015: W. Haak/I. Lazaridis/N. Patterson/N. Rohland/S. Mallick/B. Llamas/G. Brandt/S. Nordenfelt/E. Harney/K. Stewardson/Q. Fu/A. Mittnik/E. Bánffy/C. Economou/M. Francken/S. Friederich/R. Garrido-Pena/F. Hallgren/V. Khartanovich/A. Khokhlov/M. Kunst/P. Kuznetsov/H. Meller/O. Mochalov/V. Moiseyev/N. Nicklisch/S. L. Pichler/R. Risch/M. A. Rojo Guerra/C. Roth/A. Szécsényi-Nagy/J. Wahl/M. Meyer/J. Krause/D. Brown/D. Anthony/A. Cooper/K. W. Alt/D. Reich, Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 2015, 207–2011.

Kaiser 2021: E. Kaiser, Population dynamics in the third millennium BC – The interpretation of archaeological and palaeogenetic information. In: In: V. Heyd/G. Kulcsár/B. Preda-Bălănică (Hrsg.), Yamnaya Interactions. Proceedings oft he International Workshop held in Helsinki, 25–26 April 2019. The Yamnaya Impact on Prehsitoric Europe 2. Archaeoligua 44 (Budapest 2021) 83–99.

Rascovan et al. 2019: N. Rascovan/K.-G. Sjögren/K. Kristiansen/R. Nielsen/E. Willerslev/C. Desnues/S. Rasmussen, Emergence and Spread of Basal Lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline. Cell 176, H. 1–2, 2019, 295–305. [DOI]

Teegen 2011: W. R. Teegen, Die Menschen aus glockenbecherzeitlichen Gräbern in Nordwestsachsen. Arbeits- u. Forschber. sächs. Bodendenkmalpfl. 51/52, 2011, 131–199.

Susat et al. 2021: J. Susat/H. Lübke/A. Immel, U. Brinker/A. Macāne/J. Meadows/B. Steer/A. Tholey/I. Zagorska/G. Gerhards/U. Schmölcke/M. Kalninš, A. Franke/E. Pētersone-Gordina/ B. Teßman/M. Tōrv/S. Schreiber/C. Andree/V. Bērzinš, A. Nebel/B. Krause-Kyora, A 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer already plagued by Yersinia pestis. Cell Reports 35, H. 13, 2021, 1–12. [DOI]

Trautmann 2021: M. Trautmann, Deadly invaders – the possible role of contagious diseases in the european Copper Age / Bronze Age transition. In: V. Heyd/G. Kulcsár/B. Preda-Bălănică (Hrsg.), Yamnaya Interactions. Proceedings oft he International Workshop held in Helsinki, 25–26 April 2019. The Yamnaya Impact on Prehsitoric Europe 2. Archaeoligua 44 (Budapest 2021) 101–123.