Ivan Kavaleridze has played a significant role in Ukrainian culture. His name, however, is little known in contemporary Ukraine, and few people have heard about him outside the country. Born in 1887 in Ukraine and of Georgian descent, he lived to the age of 91, spoke and wrote in Russian, but was obsessed with Greek mythology and Ukrainian romantic poets and philosophers. Taras Shevchenko and Hryhorii Skovoroda were among his favorites.

Kavaleridze was one of the first Ukrainian film directors to make historical movies about revolutionary Ukraine, or describing events that took place in pre-revolutionary times. In 1929, the year he debuted as a film director, Kavaleridze was already an acclaimed sculptor, having studied in Paris alongside Oleksandr Arkhypenko, a Kyiv classmate, avant-garde artist, and sculptor. In 1918, he made the first large-scale post-revolutionary monument to Taras Shevchenko for the town of Romny. Shevchenko was the author of the two poems that inspired the movie Prometheus: The Caucasus and A Dream were written as a meditation on the Russian imperialist wars in the Caucasus. Kavaleridze is also known as the creator of two concrete Constructivist sculptures of Artiom, in Bakhmut (1924) and Sviatohirsk (1927). The first was destroyed during the Nazi occupation, but survived on film (in Kavaleridze’s Perekop and Vertov’s Enthusiasm: The Symphony of the Donbas). The second monument is still there, surviving the Russian invasion.

Modell des "Monument to Artjom" in Swjatohorsk (1926), in der Ausstellung "Kaleidoskop der Geschichte(n)" im Albertinum (2023)

© Courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine [NAMU], Foto: Jacob Franke

Six years after his first feature film, to commemorate the fifteenth anniversary of Soviet cinema, Kavaleridze was awarded the Order of the Red Star. By then, he had made five feature films: The Downpour (1929), Perekop (1930), Storm Nights (1931), Koliivshchyna (1933), and Prometheus (1936). All of these were criticized for being too static; for not being “filmic” enough.

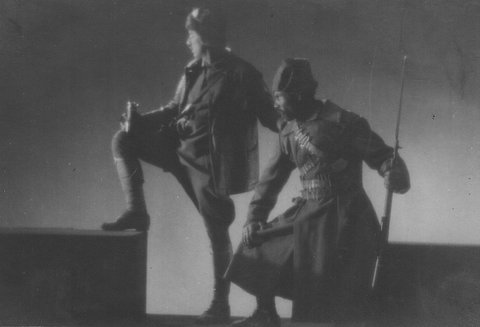

Filmstill aus Ivan Kavaleridzes "The Downpour" (1929)

© Courtesy of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Center (Kyiv)

Kavaleridze’s movie debut, The Downpour, is a story about Koliivshchyna, a popular uprising by haidamaky (Ukrainian paramilitary units) against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 18th century. The director described the genre of Downpour as a “cinematic experiment” and shot the whole movie indoors in a pavilion the size of a soccer field. At the time, Oleksandr Dovzehnko’s Arsenal (1929) was considered the most impenetrable Ukrainian movie, but after Downpour was screened, one critic wrote that Arsenal seemed simple and clear-cut in comparison.

The movie was released in March, 1929, heavily promoted by the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration —VUFKU — and praised as an achievement of Ukrainian experimental cinema. However, members of the proletariat who watched the movie were far from satisfied. They did not buy the idea of a revolution perpetrated by black cubes and static images of characters. It was too symbolic and too slow for supporters of working-class culture or Proletkult. Downpour was banned by Moscow authorities shortly after the premiere, foreshadowing the fate of subsequent Kavaleridze movies.

Filmstill aus Ivan Kavaleridzes "The Downpour" (1929)

© Courtesy of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Center (Kyiv)

The next movie, Perekop, Kavaleridze dedicated to events that had taken place recently, namely the Perekop-Chongar operation (1920), during which the Red Army took Crimea and, according to the Soviet writing of history, won the “civil war.” Criticized for its lack of plot and misuse of visual effects, the movie was also recommended to be watched with an explanatory commentary that aligned Kavaleridze’s broad analogies in a clear, ideologically acceptable narrative.

In 1927, the construction of the hydroelectric plant DniproHES started, and immediately became an epic cinematic event for many film directors. Kavaleridze was not an exception: he created his third movie Stormy Nights. Despite its star-studded cast and topical subject matter, the movie ended up being banned.

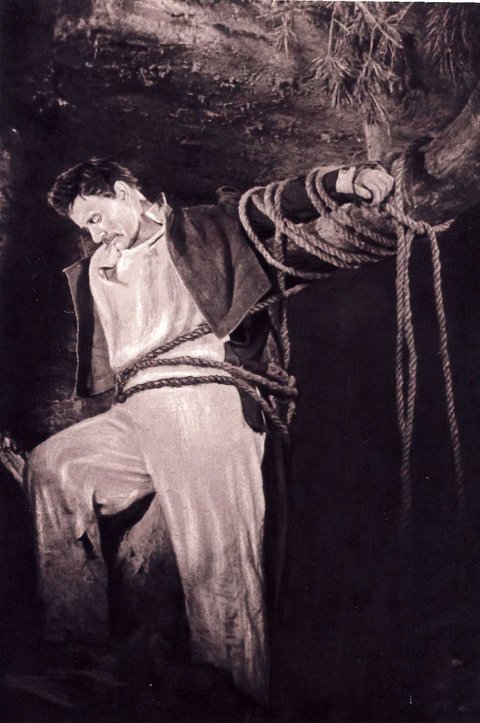

The first sound film Kavaleridze directed, Koliivshchyna, was hastily banned from distribution too, despite 17 script rewrites under pressure from the party leadership. It had been envisioned as part of a large-scale trilogy on three centuries of the liberation struggle in Ukraine, to be followed by two more movies: Prometheus and Dnipro. However, the “liberation trilogy” came to an end with Prometheus, shot at the Kyiv Film Studio. The movie deals with Ukrainian peasants suffering from serfdom under the Russian Empire. A landlord sends his serf Ivas, our main protagonist, to the Caucasus as a soldier, while Ivas’s bride is forced to work in a brothel. Under the influence of the revolutionary Gavrilov, Ivas becomes a politically aware fighter and, upon returning to the village, starts a peasant uprising.

Ivan Kavaleridzes: "Prometey" (1936)

© Courtesy of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Center (Kyiv)

Though superficially in line with Soviet politics, the movie provoked critical outrage in both Ukraine and the Soviet Union. To find the reason for the Prometheus controversy, we need to go back four years to 1932. That was when Stalinist Socialist Realism replaced the utopian revolutionary culture of the 1920s, shaping the future of Soviet art pretty much until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Socialist Realism drew not only on the classical tradition of nineteenth-century Russian literature but also on a “sober,” non-utopian view of life. From that perspective, Socialist Realism constituted a “realistic” reaction to the collapse of modernist experiments and the future-oriented projects of socialist art before Stalin. According to the evangelists of Socialist Realism, Soviet artists needed to restore the Classical unities—unity of time, unity of place, and unity of action—inspired by Aristotle’s Poetics.

What mattered here, however, was not only poetics but politics: Socialist Realism was a politico-aesthetical project. As Boris Shumyatskiy, the head of the Soviet film industry, proclaimed in 1936, formalist film directors were the worst storytellers because they did not have a firm, ideologically coherent worldview. In that context, Soviet cinematographers were “recommended” to reject avant-garde experiments with imagery and storytelling and to start making movies in a classical, almost Hollywood tradition. Stalin was a big fan of American cinema. Straightforward plot structures, clear ideological messages, and a sharp contrast between good and bad are the iconic hallmarks of exemplary Soviet cinema from the Stalinist era and beyond. By 1936, these aesthetic guidelines had become the political norm. In January, the central newspaper Pravda published an article “Confusion Instead of Music,” in which Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was fiercely criticized by the Moscow authorities. Retrospectively, it inaugurated an ideological campaign against formalism (“domination of form over content in art”).

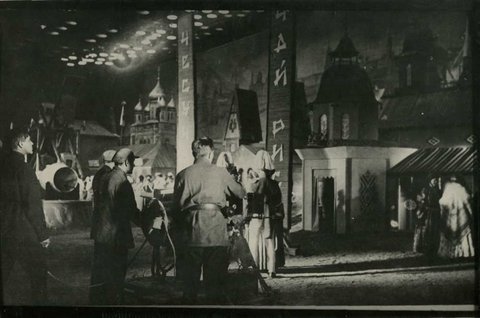

Kavaleridze started to film Prometheus long before this, and in a less hostile environment. The approach he took to the movie was quite similar to his earlier work. Drifting away from the conventions of realism, Kavaleridze created a highly static, controlled environment where light and shadow are much more important than camera movement.

Dreharbeiten für Ivan Kavaleridzes: "Prometey" (1936)

© Courtesy of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Center (Kyiv)

In 1934, Ukrainian cinematographers praised Prometheus’s script for its high artistic quality, and for revealing the exploitative nature of feudal tsarist Russia and its colonization policy. The script was approved and production was green-lighted. A year later, the political climate changed significantly. The ideologically correct plot about the revolutionary struggle against tsarist oppression was not enough to save the movie from criticism. The way it was filmed became equally crucial. It was at that time that history was being written anew: commitment to the revolutionary movement and fascination with the people’s struggle were being replaced by the rehabilitation of the tsarist autocracy. In Peter the Great (1937) and Alexander Nevsky (1938), the images of the strong leader, designed to legitimize Stalin’s quasi-monarchist policy, are all too easy to recognize. It comes as no surprise that state officials wanted the already filmed Prometheus re-edited to meet the new political agenda. It was too anachronistic, too devoted to the ideals of the Revolution, and too focused on the ordinary man.

The anachronism of Kavaleridze’s movie is also played out on another level: the linguistic one. Two sound movies that Kavaleridze had made by this point—Koliivshchyna and Prometheus—are perhaps the most striking examples of the phenomenon of cinematic “multilingualism.” The different nationalities and ethnic minorities in these movies speak their native languages, be it Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, or Yiddish, but somehow manage to find a common ground and understanding. In an attempt to justify the use of this artistic technique in Prometheus, Kavaleridze claimed that although all the characters in the movie speak their own language, they actually speak the same language: the language of the coming Revolution. Despite all differences between its citizens, the Soviet Union was expected to become a space of mutual understanding with no contradictions.

However, the revolutionary moment passed, and social reality did not meet expectations. Equality of the peoples and cultural pluralism were replaced by a new asymmetry legitimized by Stalinism: russification. In the new political situation, only Socialist Realist movies made exclusively in Russian were approved for distribution. Even Stalin himself, who spoke with a heavy Georgian accent in real life, and who positioned himself as the leader of all the peoples of the USSR, welcomed the performance of his role in pure Russian by the actor Aleksei Dikiy in the movies The Third Blow (1948) and The Battle of Stalingrad (1949).

Within a few months, Prometheus was banned for the perversion of reality, formalism, and naturalism. Critics complained that the characters were unconvincing, the overall pace and rhythm of the movie were too slow, the editing was not rigorous enough and the frogs were too naturalistic. From that point on, to kill the movie, it was enough to accuse it of bourgeois nationalism, naturalism, and formalism. No one understood what those words really meant, but they became a universal tool for attacking ideological opponents. Predictably, Kavaleridze was accused of ignoring Socialist Realism norms, resorting to underhand sociological tactics, distorting history, presenting anti-social subject matter, and using crude naturalistic techniques and formalistic trickery that made the movie incomprehensible to the proletarian viewer.

Filmstill der "zu naturalistischen Frösche" in Ivan Kavaleridzes: "Prometey" (1936)

© Courtesy of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Center (Kyiv)

Some Ukrainian movie critics claimed that Prometheus provoked a negative reaction from Joseph Stalin himself, who was known to have shaped the cinematographic repertoire of the USSR to suit his own taste. It was supposedly on his personal order that on February 18, 1936, the newspaper Pravda published an editorial by Odesa-born Mykhailo Koltsov (who brought his fellow director Dziga Vertov into the movie industry) entitled “A Rough Sketch Instead of Historical Truth.” The article campaigned for anti-formalist tendencies in Soviet cinema.

Despite all this, Kavaleridze’s Prometheus remains one of the most important Soviet movies of the 1930s. It was through no fault of its own that the movie found itself at the center of the key disputes of this crucial period in the history of the Soviet Union. If the article “Confusion Instead of Music,” written about the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and published in Pravda newspaper, is considered the most important text marking the transition to Socialist Realism art and Stalinist cultural hegemony, Prometheus is the iconic target of anti-formalist criticism not only of Ukrainian but more broadly, Soviet cinema of the period.

Also of interest:

The annihilation of Vinh City by US bomb raids offered an opportunity for experimental planning and for transforming the small industrial town into a model socialist city. The GDR’s ambitious task of comprehensive reconstruction involved working collectively on both the creation of a master plan and its realization in built form. Christina Schwenkel on the Quang Trung housing complex.

On 13 October 2022, the Albertinum of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden hosted the conference “Revolutionary Romances: Into the Cold – Alternative Artistic Trajectories into (Post-)Communist Europe.” A report by Julia Tatiana Bailey and Christopher Williams-Wynn.

A pub in the museum? There are many inviting, sociable places in Leipzig. In recent years, numerous old pubs have had to close, including the Weißes Roß ("White Horse") owned by Jens-Thomas Nagel. It was located near the Grassimuseum, today it is housed inside of it.