Not many designers enter into their work by falling in love with a plant. And Japanese knotweed is not just any plant; it is one of the most charismatic villains of the vegetal world. Successfully colonising the continents by casting its roots from Japan to the US, other parts of Asia and Europe, it is known as one of the most invasive plants on Earth and a serious threat to biodiversity. Simultaneously, knotweed is gaining attention as an exceptional medicinal plant, a tasty substitute for rhubarb and a late-summer food source for foraging pollinators. So, why not also consider this omnipresent pest as a local resource to produce paper?

Knotweed harvest [Knöterich-Ernte]. Slow disturbance events from the Series: Feral Occupations: ‘Our labour is our infrastructure’, Krater collective for 35th Graphic biennial Ljubljana.

© Amadeja Smrekar

Harvesting knotweed to create an urban paper product line brought us closer to feral ecologies where invasive plants thrive. Such ecologies can be found on abandoned construction sites, railway routes and highways or neglected ruins; man-made spaces that have usually been disturbed by large-scale machines and extensive infrastructural projects. Containing unexpected assemblages of construction materials, native and exotic species, and feral lands trigger our curiosity and imagination.

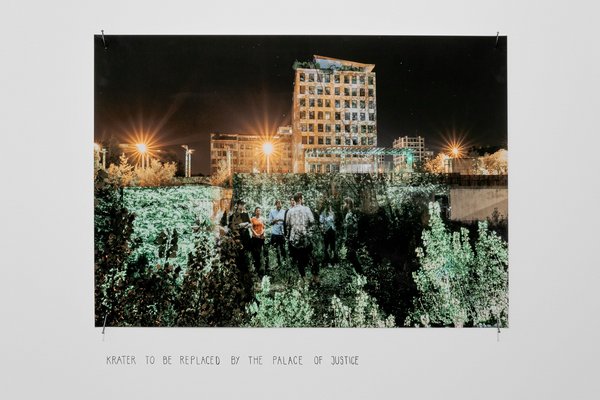

In our quest not only to harvest invasive plants but also to work from and with feral sites, we sought a plot in the city. The site named “Krater” was discovered next to one of the busiest roads in the Bežigrad neighbourhood, by climbing the metal fences. Transcending the notion of an idyllic wilderness, the yet-to-be-discovered land gradually revealed itself to us as a place of many conflicts: a pit awaiting construction, a plot infiltrated by pests and invasive plants, and a poignant reminder of a failed state investment. Within Krater’s troubled terrain, a dichotomy emerges; it harbours numerous challenges while providing a unique space to see and to act differently.

‘A collection of travelling plants’ reveals colonial and industrial (hi)stories of plant invasions

© Klemen Ilovar, courtesy of Trajna

Wilde Samen als blinde Passagiere und Reisbegleiter - ‘Blind Passengers Mobile’ Invasive species are often our hidden travel companions, transported globally by rail, car or ship. “Notweed” paper product by Trajna

© Klemen Ilovar, courtesy of Trajna

Der verwilderte Ökosystem Krater in Ljubljana/ Krater feral ecosystem in Ljubljana

© Aljaž Plankl

Institutional occupations: Under construction, 2023, Japanese knotweed bush, permission not-to-mow. From the Series: Feral Occupations: ‘Our labour is our infrastructure’, Krater collective for 35th Graphic biennial Ljubljana

© Amadeja Smrekar

A contractual agreement with the site manager – the Ministry of Justice – paved the way for reopening the neglected public land. The act of cutting through a construction fence to install the door not only reintegrated the space into the urban fabric but also brought the site back into the public’s collective imagination. However, as visitors entered this remarkable urban space, a crucial aspect came to light: public access cannot be assured at all times. Signs posted at the entrance remind visitors to respect the vulnerable urban fabric, emphasising its role as a place of multi-species care and repair. Krater is a sensitive site that hosts the flourishing and decomposition of many pioneering species, revitalising once abandoned grounds. It houses various multispecies interactions, such as providing nesting grounds for birds and food for pollinators, fostering soil formation, facilitating insect communication, and enabling winter hibernation. Despite, or perhaps because of, its inaccessibility, Krater is a feral typology of a public green space maintained by a collaborative effort involving creatives, ecologists, plants, soil, animals and other participants, rather than relying on city mowers and machines.

Krater Collective 2023 from left to right: Amadeja Smrekar, Sebastjan Kovač, Maša Cvetko, Andrej Koruza, Danica Sretenović, Rok Oblak, Paulin Liogier, Edern Haushofer, Gaja Mežnarić Osole, Altan Jurca Avci, Primož Turnšek, Anamari Hrup. Not in the photo: Eva Jera Hanžek, Juan José López Díez, Louisa Selleret.

© Amadeja Smrekar and Daša Bezjak

The Krater collective is a group of transdisciplinary enthusiasts who were courageous to reinvent their respective professions, studios and working conditions to act as guardians of a rewilded ecosystem at the pending construction site in Ljubljana. Since Krater’s ecosystem is constantly on the verge of extinction, they cultivate creative resilience in the face of urgency by inventing wild tactics, events and formats, treating administrative constraints and other restrictions as the subject of artistic interventions. This action calls for unexpected alliances and inventive economies to open up new fields of regenerative, relational and critical creative practice. Alongside site-specific work such as the cultivation of biodiversity, Krater hosts internationally acclaimed educational formats to introduce new typologies of work into human culture (The School of Feral Grounds), laboratories to experiment with biomaterials (“NotWeed” paper, invasive plants, mycelia and wild clay), advocacy strategies (banquets, mediation processes, public speeches), exhibitions (Forbidden Vernaculars BIO27, Feral Occupations GB35), conferences (The Feral Palace), and other public programmes (Krater Vibrascapes, harvesting Japanese knotweed, Feral Cartographies Cycling, Tea Ceremonies, Little School of Urban Ecologies, etc.). Krater was a finalist at the New European Bauhaus Prizes in 2021. In 2023, the project received a special mention at the 35th Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana and the highest Slovenian accolade bestowed on architecture for public spaces: the Plečnik Award.

Krater Collective includes a diverse multispecies community thriving at the site

© Amadeja Smrekar

At the Little School of Urban Ecology, children are crafting planting pots using invasive black locust, prospering on the site

© Amadeja Smrekar

The collective’s initial goal in moving onto the construction site was to host material production stations allowing people to experiment and design with invasive plants and other unconventional materials found in the city, such as wild clay, mushrooms or waste materials. For that reason, a wood workshop, a paper and clay workshop and a mycolab were carefully set up on the site. Inspired by the insights of environmental justice scholar Catriona Sandilands, the collective engaged in harvesting as a means of caring for the feral land and its many thriving species. The collectives aim was not only to design products and materials on the site – such as paper pots made from invasive plants or infrastructure made from rammed earth – but also to cater for the needs of the ecosystem from which they took the materials. Unlike current trends in design and architecture that promote organic, locally sourced materials without addressing their mass depletion, Krater was instead intended to experiment with regenerative material cultures.

Krater’s wild clay

© Amadeja Smrekar

In paper laboratories, we experimented with manual paper-making processes, creating samples from invasive plants such as thorny Robinia branches, Canadian goldenrod and Japanese knotweed stems to test them for industrial production. Paper attracted our attention as one of several materials that are becoming increasingly popular in various sustainability-driven applications. With the ban of many plastic-based products and the rise of online shopping, the demand for paper has increased drastically in Europe. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, tree plantations have expanded by 50% in the last thirty years, greatly increasing the threat to terrestrial biodiversity. "Notweed” paper, which is locally sourced from invasive plants, was introduced to enable designers to contribute to material practices that reconnect people with the local landscapes. By harvesting the abundant Japanese knotweed, usually known as an unwanted pest that must be eradicated, we created a sustainable paper alternative. Replacing virgin wood cellulose from tree plantations with knotweed fibres has established an economy that not only yields a local product from ‘unwanted material’ but also challenges warlike strategies centred on invasive species and engages the local community in learning about damaged ecosystems. Importantly, producing “Notweed” paper diversifies the collective’s income by reducing its reliance on competitive public funding and supports economic resilience in our eco-social design activities.

Sustainability in design is not just about inventing new products from local materials and waste products, or curating ecological themes. To be truly sustainable, it also means recognising and critically examining the reproduction of inequalities at work, in nature and in our culture. To sustain its public presence, Krater frequently contributes to biennials, exhibitions, workshops and guided tours. However, these institution-led activities often fall short in providing the support needed for the collective to survive in the long term.

Banquet of Feral Occupations. Krater collective for 35th Graphic biennial Ljubljana, 2023

© Amadeja Smrekar

The Banquet of Feral Occupations, organised as part of the public programme of the 35th Biennial of Graphic Arts, was hosted to explore new paths of solidarity between public institutions and the independent scene. Delegates from institutions and NGOs, alongside the Krater collective and attendees of the 35th Biennial of Graphic Arts, gathered in the rewilded construction site to discuss what needs to change if we want to preserve Krater’s creative practices for the future. As a platform for bottom-up diplomacy, the banquet proposed funding tactics to ensure that urgent discourses continued, strengthened alliances and introduced novel legal entities for preserving wild urban sites. One prominent question that we addressed focused on the protection and creation of new public green spaces in the city amidst rapid urbanisation and the influence of capital-based interests.

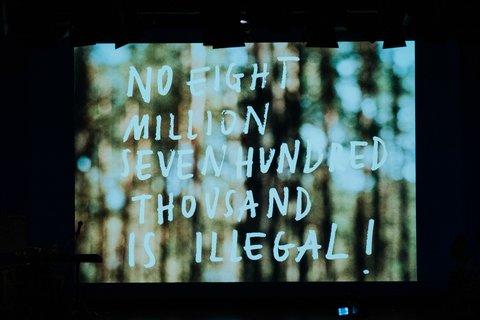

Due to a lack of operational policies or legal advocacy tools that took the value of wild sites into account, plans were made in 2021 to replace Krater’s multispecies community with the Palace of Justice, comprising three courts of justice and an adjacent park. Going three stories under the ground, it would require the whole area to be excavated. Within the tendering framework of a national architectural competition, the Krater site was evidently understood as a blank slate. Its interdisciplinary community was thus called upon to find a meaningful way to react to its inevitable erasure and raise the following questions: What makes regenerative, nature-led processes invisible to the planning authorities? Is there enough room in this notion of (spatial) justice to include the rights of the non-humans that indisputably co-constitute our living environments?

Feral Palace Conference 2022: Exercise in Intraspecies Democracy (Ola Korbańska, Iwo Borkowicz, Lara Jana Gabriel, Lidija Pranjić Ajda Biček).

© Amadeja Smrekar

The Feral Palace educational programme was initiated as a reaction to new state-led development plans envisioning the extinction of the delicate ecology emerging on the Krater site. The collective reflected the issue facing the vulnerable area by announcing a parallel open call for a Feral Palace as a creative intervention into what could be seen as Krater’s only possible future. Landscape architects, building architects, designers, lawyers and ecologists were asked to propose alternative means of dealing with this piece of urban land, so animated yet so invisible in administrative documents. Instead of Krater being treated as a blank slate, set to be paved over by a new urban infrastructure, proposals such as mapping soil archives, the rights of spontaneous natural environments and evacuation strategies are arising as new advocacy mechanisms in a discussion with local stakeholders about a Palace of Multispecies Justice.

Feral Palace Conference 2022: Strategies of Evacuation (Jana Vukšić, Filipa Valenčić, Iskra Vukšić, Lotte van der Woude, Urška Škerl)

© Amadeja Smrekar

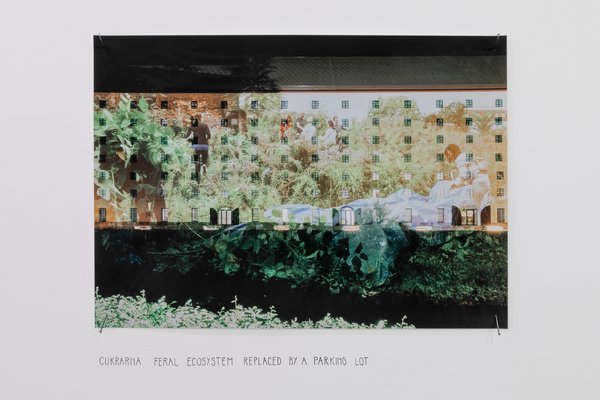

While Krater continues to flourish as an urban commons, it is considered an unregulated area by Ljubljana’s city authorities, whose approach to environmental regeneration and community engagement is undergoing scrutiny. The general urban plan categorises the Krater ecosystem as suitable for development, while a golf course on a former waste dump, and the Roma community’s relocation in favour of a leisure park, are promoted as “green regeneration”.

The Krater case is not the only one of its kind: there is a recognisable practice of encouraging urban regeneration by cleaning up unsightly messes (whether invasive plants, urban nature, civil initiatives, squatting or homelessness, etc.). Seeing Krater not as a plot of land limited by its administrative boundaries, but as a node in a web – a connector enabling multiple species to transit Ljubljana – is crucial to stop the further fragmentation of the city’s green spaces. The main problem with the radical erasure of such sites is that this cuts off the routes used by wildlife. When we design urban green spaces that are not close enough, large enough and biodiverse enough, urbanisation contributes to large-scale species extinction.

You can find the Krater Collective on Instagram, Facebook and the Internet. You can learn more about the Notweed paper here.

Also of interest:

In this article, Taiane Linhares introduces plant storytelling as a method for reconnecting to ancestral wisdom and relating to unfamiliar places and cultures. In her crash investigation during the Design Campus in Pillnitz, she used a family story involving a plant relative to develop connections to the royal garden’s Palmenhaus. The result of this research was a mixed-media piece expressing the local and global impacts of the colonisation process and its persistence.

What remains of us? Currently quite a lot. In her film collage "Die Hüter des Unrats - eine kurze Geschichte des Abfalls" (The Guardians of Garbage - A Short History of Waste), which can currently be seen at the Japanisches Palais, Susann Maria Hempel takes a sarcastic look at the way we deal with waste and its ecological consequences. About the stomachs of predatory fish, chickens and giant tortoises as an archive.

Inspired by ongoing initiatives and projects of contemporary international designers, engineers, artists and writers, the following phyto-based actions are not addressed solely to practitioners, but call for everyone's (including producers’ and consumers’) sense of respect, responsibility, equity and empathy towards plants. They should be read not as rules but as invitations to see the world through the perspective of plants.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/e/csm_Plant_Fever_The_Manifesto_of_Phyto-centred_Design_Photo__c__Olly_Cruise__studio_d-o-t-s_-_Horizontal_cut_High_Res_96813b1039.jpg)