Taiane Linhares, ihre Großmutter und Coco de Macuco vor dem Haus der Großmutter

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

In my grandmother’s front yard there is a coco de macuco palm tree that is more than 70 years old. This miniature palm, known by botanists as Syagrus weddelliana, is endemic to my home, Magé, a region in the middle of the Atlantic Forest, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In front of the centenary house, coco de macuco appears in the most emblematic family portraits as a kind of plant relative, small for a palm, but gigantic compared to the height of the women in my family, which is mostly below 1.55 m or five foot one.

Taiane Linhares, ihre Großmutter und Coco de Macuco (links) vor dem Haus der Großmutter

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

During these 70 years, the coco de macuco has seen my great grandmother and my grandmother widowed at almost the same age, and respectively struggling to keep 5 and 6 small children alive. The coco de macuco has seen children from all over the neighbourhood running around that house playing cops and robbers. My mother and her siblings married in that same house, had healthy children who played in the front yard and ate the little coconuts from the coco de macuco.

The importance of coco de macuco goes beyond my family story. For decades, poor peasants of all ages supplemented their income by collecting little coco de macuco coconuts from the middle of the wild forest. They would sell bags full of “coquinhos” (small coconuts) to intermediaries from the big city. According to legend, coco de macuco was used to manufacture cosmetics in France, but in reality, no one knows exactly what it was used for. As the intermediaries stopped coming in the 1980s, the mystery remains unsolved.

Taiane Linhares: "Coco de Macuco", 2023 im Pillnitzer Wasserpalais

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

Plants have the ability to establish strong relationships with their environment, which often includes humans. These inter-species relations are local and rarely documented in botanical databases, which best serve the practices of collecting, classifying, and archiving. The same can be said about botanic collections and greenhouses such as the one we find in the Pillnitz royal garden: the Palmenhaus, built in 1859 in the section known as the Dutch Garden. My first expectation of a Dutch Garden is a field filled with tulips of all colours. Tulips, a Dutch national symbol, but not native to the Netherlands, having being cultivated by the Turks 3000 years ago. Reality, however, is a lot less pleasant: this area is called the Dutch Garden because it was dedicated to plants collected from former Dutch colonies, such as South Africa.

The present Palmenhaus collection dates from 2009, when the greenhouse was reopened. Although the greenhouse was recently renovated, the plant collection still follows its original colonial curatorial principle of displaying “Dutch and New-Dutch plants from South Africa, and Australia”, to use a description borrowed from the explanatory text in the Palmenhaus exhibition.

Palmenhaus in Pillnitz

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

As in other botanic collections, the plants here are identified by their botanical family, their common name (in German), their scientific name and a vague label of their origin. In the accompanying exhibition, much is said about the many greenhouse reconstructions. The educational text is very detailed in describing the materials that were used to erect this wonder of German engineering, but almost no attention is dedicated to the plants brought from so far away to inhabit this glass prison. Their original environments, their local usages, and the colonial exchange processes that enabled generations and generations of tropical plants to inhabit the Palmenhaus are topics not worthy of mention.

In the fourth chapter of the Plant Fever exhibition in the Pillnitz Park and Palace museum, the main room is devoted to the history of the garden. Entering this room, visitors see a map on the wall displaying Pillnitz’s network of contacts with royal gardens and botanical institutions. Interestingly, the web does not spread over the European continent: it is an institutional network rather than a network of plant suppliers. The choice of focusing on showing relationships between men and institutions, instead of plant stories, replicates the structure of historical and botanical databases, which are often personalistic, male-dominated and guided by economic interests, and usually appropriate or erase local and indigenous knowledge.

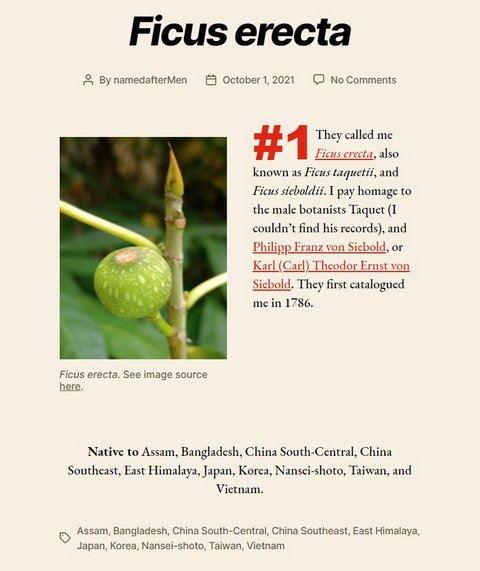

Collections and databases are not neutral artefacts, but the result of human judgement about what objects and knowledge are relevant enough to be retained over time. A lot can be learnt about Western culture by investigating the imprints left by human decision-making in the field of botanical taxonomy. In 2021 I launched the project named after Men, a bot that posts one plant that was named after a male botanist every day on a website. In the post, an image of a plant is displayed alongside a hyperlinked text in which the plants introduce themselves in the first person, translating plant descriptions from botanical and public databases into readable language. Additionally, some of the plants and botanists are linked to their Wikipedia articles. Looking at the information, users can read between the lines and identify stories that connect the cataloguing of plants and naming processes to histories of colonial enterprise.

Ficus Erecta in Taiane Linhares: "named after Men", 2021

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

The effectiveness of this storytelling framework was revealed in the very first post, about the plant Ficus erecta. Beside a scientific name, plants also have synonyms, which are failed attempts to register a new species name because the plant was already catalogued. One of the names attributed to Ficus erecta is Ficus sieboldii, which honours the German physician, botanist, and traveller Philipp Franz von Siebold, who died in 1866. Siebold was an army medical officer for the Dutch East Indies, a Dutch colony in East Asia, and worked six years for the Dutch in Japan. During that period, Siebold was involved in several illegal activities, which culminated in him being banned from Japan under an accusation of espionage. Siebold was also responsible for introducing Japanese knotweed in Europe and North America, an invasive weed which damages all kinds of concrete foundations, causing, for instance, the weakening of flood defences, and encouraging fires. Incidentally, a project dedicated to using Japanese knotweed to produce paper is showcased in Plant Fever Chapter 1, “Plants as Resources”.

During the School of Phyto-centred Design, I used knowledge bases’ capacity for unintentionally telling stories to connect with the Pillnitz Park and Palace. To start, I documented all the plants I could find in the garden from the Arecaceae family, popularly known as palms. The small dataset contained species native to four continents: Oceania (3), Africa (2), Europe (1), and North America (1). Searching for their scientific names in Wikipedia, Kew Plants of the World, and the Biodiversity Library, I found some golden threads that formed a basis for plant stories.

Taiane Linhares: "Coco de Macuco", 2023 im Pillnitzer Wasserpalais

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

One of the Palmenhaus species, Chrysalidocarpus lutescens, caught my eye as its leaves had similarities to coco de macuco. I decided to dig deeper in the database records for this species from Madagascar, and surprisingly discovered one aspect that connected it to my palm relative: they were first mentioned in the botanical literature of the 19th century by Hermann Wendland, German botanist and gardener of the Royal Gardens of Herrenhausen in Hannover. The Royal Gardens of Herrenhausen had the biggest collection of palms in continental Europe and is one of the institutions linked to Pillnitz in the exhibition map previously mentioned in this article. In my imagination, I could see C. lutescens providing shade to coco de macuco in the Herrenhausen greenhouse of the 19th century.

Unlike coco de macuco, with whom I can connect through local stories, C. lutescens’ presence in the greenhouse is impersonal. Besides being one of the most popular ornamental palms, having spread all around the world, the most intimate information I could find about it was its native name among the Betsimisaraka people: lafaza. Having a native name recognised in botanical databases as a common name is a great achievement. An Internet search for the term coco de macuco on the day I am writing this article would give the impression that this name was invented by me. This local name for Syagrus weddelliana means “the ground bird macuco’s coconut”, and reveals the palm’s relationship to the bird species Tinamus solitarius. It is neither a recognised common name, nor it is cited in the Wikipedia article for the species Syagrus weddelliana.

Taiane Linhares: "Coco de Macuco", 2023 im Pillnitzer Wasserpalais

© Courtesy of Taiane Linhares

To consolidate the reflection on this topic, I created the mixed media piece “Coco de macuco”, which puts lafaza and coco de macuco together in the context of 19th-century royal gardens. The 1x2-metre piece has two transparent layers. In the background, the palm’s relationships to the macuco bird and extractivist workers are represented by a drawing on translucent paper; these images are partially hidden by a fabric foreground connecting Pillnitz to Herrenhausen and providing a link to lafaza and coco de macuco (represented here by botanical attribute labels such as their scientific name, genus, year of description, and height). The story this piece tells is one of unknown plant stories still waiting to be unveiled. Getting to know our plant relatives and neighbours is not only an attempt to nurture closer relationships with non-human entities, but also a way of reconnecting with ancestors and with the land we are in.

Acknowledgements: the author would like to thank her grandmother Lina, her uncle Pierre, and Dona Dejanira, who preserved and shared their knowledge about coco de macuco.

Also of interest:

Power Games – Of Pleasure Gardens and Golf Courses

Katharina Mludek took part in this year's Design Campus at the Museum of Decorative Arts, which was all about plant fever. She wrote for us about pleasure and play in the (Pillnitz) garden and about who actually cultivates whom in the garden.

Design Campus 2023: Becoming Plant

This year, the Design Campus at the Kunstgewerbemuseum is all about plants. In their opening lecture for the Design School, design duo d-o-t-s, who also curated the exhibition Plant Fever, call for a rethinking of the relationship between humans and plants. d-o-t-s on the invention of the salt shaker and rooting robots.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/2/csm_230721_Becoming_Plant_OCo_Inauguration_Lecture_Slides_page-0012_1769982be8.jpg)

Poolpropaganda in Wermsdorf

The swimming pool is a place of community. Based on the idea that society gathers here in all its diversity, the SKD's Outreach and Society Department had an outdoor pool built next to the hunting lodge in Wermsdorf for the last weeks of the school holidays.