A decade of relentless air strikes by the United States during the Vietnam War between 1964 and 1973 devastated the industrial city of Vinh in the north-central province of Nghệ An, the cradle of the revolution and the homeland of Hồ Chí Minh, North Vietnam’s first postcolonial president. Mass bombing not only mobilized the Vietnamese population, but also galvanized movements of anti-imperialist solidarity around the socialist world, including in the GDR. Along with other Eastern Bloc countries, the GDR subsequently agreed to help Vietnam rebuild at the request of the Vietnamese government. Its modernizing task, as per the final agreement signed on 22 October 1973, was to assist with the comprehensive “design and construction of Vinh City”. This led to the collaborative “building of socialism” with the goal to advance the Vietnamese nation to socialist industrial modernity.

Zerstörung durch Luftangriffe in Vinh

© CC BY-NC-ND (Link am Seitenende), Foto: Hồ Xuân Thành

Both national interests and global ambitions motivated the GDR’s support of North Vietnam (also known as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam). North Vietnam had been one of the first countries to receive aid from East Germany in the 1950s at a time when the GDR’s own economy was recovering from the Second World War. In the early years of Vietnam’s decolonization, GDR support aimed to modernize North Vietnam through construction of new infrastructure and industry, which would be the driver of postcolonial growth, along with support from other socialist countries. By the end of the war with the United States in 1975, the GDR had emerged as one of the largest providers of “socialist assistance” to North Vietnam, second only to the Soviet Union.

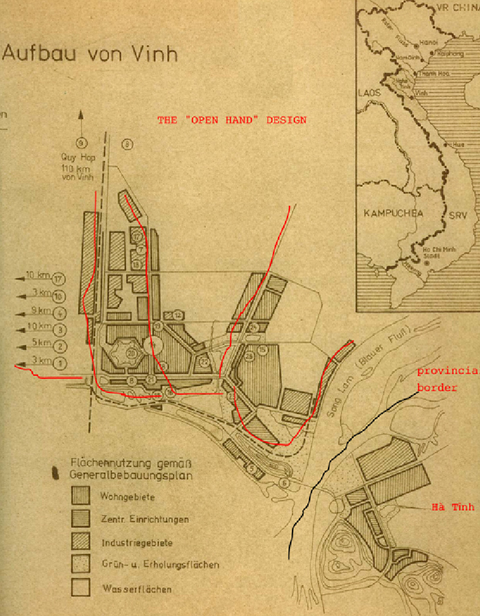

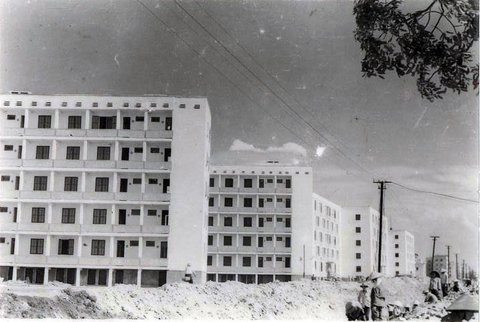

The annihilation of Vinh City by US bomb raids offered an opportunity for experimental planning and for transforming the small industrial town into a model socialist city. The GDR’s ambitious task of comprehensive reconstruction involved working collectively on both the creation of a master plan and its realization in built form. Their holistic approach to urban planning included a focus on laying new urban infrastructure, developing the construction industry, training its workforce, and housing its workers in the city’s first planned residential community for 15,000 inhabitants, called Quang Trung housing complex (khu chung cư Quang Trung). To tackle the severe housing shortages faced after the war, architects turned to the spatial-architectural idea of the integrated housing estate, or microrayon, to house a population returning from years of evacuation. Attention was focused on building both physical infrastructures, like pipes, roads and industry, but also social infrastructure like parks, schools, and markets—and a vocational training center—to create a worker-oriented city.

Entwurf der DDR-Planer für Vinh: "The Open Hand Design",

© CC BY-NC-ND (Link am Seitenende)

An international group of (mostly GDR-trained) Vietnamese and East German architects, engineers, and urban planners, referred to in the press as the “children of the homeland of Marx”, as well as a large cohort of mostly female construction workers, would spend the next seven years applying rational planning principles and social scientific knowledge to creating a radically new urban environment. A clear racial and gendered division of labor emerged in this collaboration despite socialism’s claims to egalitarianism: Vietnamese men, under the tutelage of German architects, engaged in the technical labor of mapping and planning, while Vietnamese women performed the hard work of land grading and then constructing the planned 36 housing blocks, typically under the supervision of male superiors, both German and Vietnamese.

The project was envisioned as holistic: The city would be designed for workers’ optimal well-being in order to sustain long-term, independent growth of the city. This would occur through mechanization of the building materials industry and the upskilling of labor through intensive vocational training, following a GDR curriculum. Housing would play a central role in the social reproduction of the workforce. The resulting planned living environment, which was customized for local climate conditions, embodied the functionalist ideals of the rational city, while showcasing East German goodwill and technical ingenuity through brüderliche Hilfe.

Despite assumption of similar aspirations to modernity, the idea of universal housing was appealing to Vietnamese planners, officials and residents at the time. Socialist planning sought to lift populations out of poverty through rapid industrial and infrastructural development to secure equitable access to public goods, while undoing entrenched colonial inequalities and collectivizing the means of production. In this instance, modernist planning and architecture were then a vehicle for decolonization and development, even as the collaboration with the socialist North, including the GDR, raised concerns about new forms of dependency.

Quang Trung housing estate, 1977.

© Nghệ An Provincial Museum

Urban reconstruction was as much a material project as it was a civilizing process meant to engineer a new socialist humanity through modernist architecture, which would increase labour productivity and create new, forward-looking socialist men and women, or socialist moderns. Modernist architecture in the form of high-rise apartment buildings would not only house a population displaced in wartime, but would create a new way of modern living in the city. In this case, this new urban lifestyle was influenced by European ideologies of social organization that centred on the nuclear family as the standard household unit, breaking with previous forms of collectivization.

Tensions between aspirational planning and post-war realities exposed the incompatibility of modernism’s universalist claims. For example, single-family housing with modern amenities—that is, with infrastructure like electricity and indoor plumbing, which many people had for the first time—would ostensibly liberate women from domestic drudgery, allowing them to become more efficient workers. But newly-built infrastructure often did not function as planned owing to critical shortages, like electricity that did not allow the pumping of water to higher stories in the housing blocks. When infrastructure breaks down, women tend to pick up the slack: in the housing estate in Vinh, disrepair disproportionately increased women’s workloads, whereas modern amenities were supposed to reduce them.

The design models and technologies that travelled between East Germany and Vietnam underwent significant modification to accommodate alternative cultural logics and ideas about socialist modernization. Vietnamese authorities were uncomfortable with the lifestyle of socialist abundance that GDR plans seemed to promise, which were contrary to post-war conditions of scarcity. For example, they were skeptical of the ideas of single-family housing, which seemed lavish for the time, and the nuclear family as the basic unit of social organization in the housing estate, which was culturally at odds with the more typical extended or 3-generation household.

Many residents in the apartment blocks also remained sceptical of their high-rise living spaces and the modern conveniences they were supposed to offer. Distinctions emerged between social groups like workers and civil servants who were housed together in the complex: some embraced high rise living which gave them an identity as modern urban dwellers, while others rejected it as culturally unfamiliar. Underlying the “horizontal solidarities” between the East Germans and Vietnamese were thus competing logics of socialism and visions of urban futurity.

Expanding living space: building new atop the old, 2011

© Christina Schwenkel

We can also see the limits of rational planning and different ideas about urban life in the redesign of living space. Functional design attempted to impose clean, modern lines on what were historically and culturally blurry boundaries in Vietnam. The GDR architects had wanted to keep separate public and private spaces—which are not clearly distinguished in Vietnam—as well as living and livelihood practices, which for Vietnamese people had always been integrated. Residents in the apartment blocks set about renovating their apartments: they added additions onto the balconies to create extra rooms or entrepreneurial spaces. They enlarged the walk-out basements, which were a unique ecological feature of the complex, turning them into shops, businesses, livestock pens, or food stands. Courtyards became markets or badminton courts, and green spaces transformed into gardens. This appropriation of public space became a defining feature of the complex that reflected its dynamic social life, challenging ideas of mass housing as stifling spaces of social isolation or concrete jungles void of urban nature and human sociability.

Vietnam’s first planned city fell quickly into “unplanned obsolescence”. Buildings meant to have a lifespan of 80 years soon crumbled into disrepair owing to state neglect and a lack of maintenance. By 2010, three decades after the last GDR experts left Vinh, more than 60 percent of the original residents continued to reside in the housing blocks, where they had lived for more than 30 years. In 2011, the apartment complex was privatized, with residents paying a “fee” to transfer ownership rights their apartments from the state to their families. After plans for demolition and reconstruction of the housing estate were drawn later that same year, some residents organized to demand the buildings be recognized as architectural heritage owing to their unique history of “international solidarity”. Residents joined together to contest, and ultimately postpone, redevelopment. Since 2017, many of the housing blocks have been replaced with high-rise condominiums, calling into question the role of past utopias in the present and the future of Eastern German housing developments across the Global South.

Redevelopment of Quang Trung housing estate, 2021.

© Christina Schwenkel

Nonetheless, despite such changes to postsocialist cities, modernization projects carried out by the GDR have left an architectural footprint of this history on Vietnam’s landscape through its technical schools, factories (including Plattenwerk), hospitals, infrastructure, and other evidence of its solidarity practices with Vietnam. Consumer objects from the GDR, too, that thousands of workers and students brought back to Vietnam, can sometimes still be found in use or on display as cherished nostalgia items, such as Simson motorbikes. Even the phrase “Vietnam Germany” (Việt Đức) has become a brand, for example for the popular “Việt Đức sausages”, the owner of whom was trained in the GDR. All of which is to say that GDR support of Vietnam continues to be remembered, valued, and, preserved as GDR history—at times even written in stone, as one commemorative plaque outside a school in Buôn Ma Thuột affirms: “The Vietnam-Germany high school was founded on 20 June 1983 in accordance with the collaborative economic and friendship agreement between Vietnam and the German Democratic Republic.”

[The text and images in this exhibit are adapted from: Christina Schwenkel, Building Socialism: The Afterlife of East German Architecture in Urban Vietnam, Duke University Press, 2020.]

Also of interest:

In 2022 and 2023, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden are fixing their gaze once again on GDR times in their research and exhibition project “Kontrapunkte” (“counterpoints”), funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. Based on their own holdings and the history of their collection, fresh perspectives are being developed on art in the GDR, how it was seen and the significance allotted to it in the past and present, with the addition of international viewpoints. To this end, a range of physical and digital formats are in the pipeline, information on which will be provided on this platform.

In the spring of 2020, a very special troupe of brightly coloured figures took up residence in the depot of the Puppentheatersammlung. Fishers and farmers, musicians and child gymnasts, not to mention ducks, water buffalos, dragons and fairies. They all belong to the classic cast of Vietnamese water puppetry.

Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran curated the first of our film series for the Kontrapunkte project, which deals with the cultural interweavings of the GDR and Vietnam. In conversation with Kathleen Reinhardt from the Albertinum, she explains the questions that preoccupied her in the process.