0. Seeing plants

Let’s start with two important questions: Why can’t we see plants? And why – when we do notice them – do we struggle to understand their complexities and their multifarious ways of inhabiting the world?

Silent and motionless, in the eyes of most people, trees, shrubs, annual and perennial plants simply form pleasant landscapes whose presence is taken for granted. We tend to regard them as mere environments or surroundings, as if their sole purpose was to be the still background in front of which our dynamic lives can quickly flow.

Coined in the late 1990s by American botanists and professors Elisabeth E. Schussler and James H. Wandersee, the term ‘plant blindness’ can be defined as the inability to see the vegetal world. Schussler and Wandersee explained this condition as the result of the limits of our visual perception, which selects only the “relevant”. Other scientists and philosophers have claimed that plant blindness can be considered rather as a mainly Western cultural phenomenon that has its roots in Ancient Greek and Christian understanding of the world: a world in which plants rank just above lifeless minerals.

© Wandersee, J. H. and Schussler, E. E.

And yet the vegetal realm accounts for 99.5% of the Earth’s visible biomass and is far from being passive. On the contrary, plants inhabit, create and design the planet as sentient living beings. Despite their apparent immobility, over the millennia, they developed ways of interacting with and reacting to the world that are plural and non banal. If we care to observe and attend them with curiosity, plants reveal capacities of adaptation and existence that go beyond our human-centred understanding of notions such as ‘intelligence’ and ‘subjectivity’. As American author Michael Pollan affirms in his book The Botany of Desire (Random House, 2001), “all these plants, which I’d always regarded as the objects of my desire, were also, I realized, subjects, acting on me, getting me to do things for them [...].”

© d-o-t-s

1. Fascination

While the consideration of plants as sentient beings might surprise many and keeps being the subject of scientific and philosophical debates, over the centuries, the vegetal realm has nevertheless managed to fascinate humans with its richness and diversity, widely nourishing the artistic and craft production of various societies in different historical periods. The applied arts collections of many international museums – see the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden’s, for instance – testify to this constant fascination. Seduced by the endless shapes and colours produced and manifested by plants, several artists, artisans, writers and inventors created objects and stories that unveil and celebrate the mystery of plants’ ungraspable otherness.

Verschiedene Ausstellungsstücke aus der Sammlung des Kunstgewerbemuseums

© Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

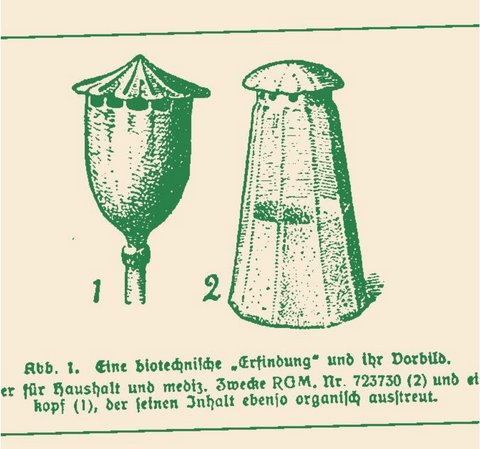

Among others, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Austro-Hungarian botanist Raoul H. Francé actively studied the vegetal world in order to understand and replicate its “inventions,” as he called them. As he states in his book Plants as Inventors (1923), in a field of flowers, Francé saw a “collection of technical miracles.” By examining from close the structures and the ways of growing of certain specimens – which are portrayed in beautiful hand drawings contained in his publication – the botanist was among the firsts to understand the potential of plant-inspired innovations in the fields of design and engineering. A simple but effective example is the salt shaker that Francé imagined after examining the way in which the flowers of poppies disperse their seeds through small holes situated at their top.

Salzstreuer und Mohn in Raoul H. Francés "Plants as inventors" 1923

© gemeinfrei

Following in the path of Francé, the 20th century saw the birth and widespread diffusion of a whole new field of technical and technological research – see the notions of ‘biomimicry’ and ‘bionics’, for reference – which aims at employing features of the natural world for the conception and engineering of human-useful tools and applications. The invention of Velcro by Swiss electrical engineer George de Mestral is a good example in that sense: in 1941, while on a walk in the Alps, de Mestral started to wonder why burdock seeds clung to his woolen socks and coat. By analysing the structure of the Great burdock’s flowers microscopically, he was able to understand the functioning of the little hooks that the plant uses to travel and establish itself in new places, and he imitated them for industrial use.

Große Klette

© Wikimedia Commons

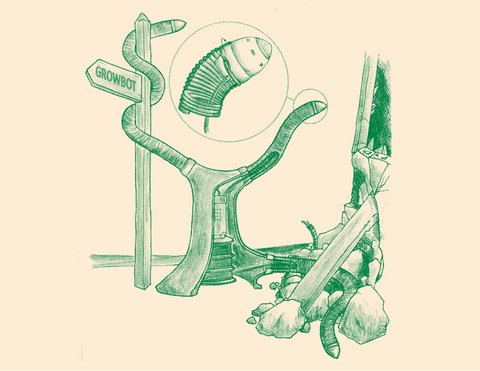

Fully embracing the idea that indeed plants possess a form of intelligence, more recently, a consortium of European academic institutions, led by professor Barbara Mazzolai of the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (Pisa, Italy), developed a new family of soft robots inspired by the growth of plants. The first of their endeavours is called Plantoid and it mimics the underground behaviour of plant roots, and their capacity to avoid obstacles and damaging substances, as well as find nutrients and water. Featuring moving and extending tips – that are enriched with sensors, and grow and infiltrate the ground thanks to an embedded micro 3D printing device – the Plantoid is able to easily navigate through soils and efficiently react to underground stimuli. Other plant-inspired inventions developed by Mazzolai and her team include Growbot and Viticcio, robots that are capable of developing branches and recognise external supports, using them to climb and expand.

Illustration des Growbot aus Barbara Mazzolais "La natura geniale" 2019

© Barbara Mazzolai/ Longanesi

2. Conversation

Design can give us the tools to reach out to plants, facilitating the understanding of their otherness. In the past years, the renewed fascination for the vegetal world by scientists, philosophers, engineers and creatives has manifested itself in a series of publications and projects that call for an intimate understanding of plants, their behaviours, needs and desires.

Inviting us to reconsider our place in a world that we cohabit with other species, thinkers such as the Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer emphasise the importance of noticing plants as this “acknowledges that we have something to learn from intelligences other than our own.” Wall Kimmerer claims that “listening, standing witness, creates an openness to the world in which the boundaries between us can dissolve in a raindrop.” Advocating relationships with non-human beings based on gratitude, she exhorts us to see plants as teachers. Her thoughts, together with those of others – such as the researcher Monica Gagliano, the biologist Stefano Mancuso, the philosophers Michael Marder and Quentin Hiernaux, and the botanist Francis Hallé – have profoundly inspired the spreading of new fields of studies around the planet. At the core of these emerging theories are a series of original concepts that are shaking Western society’s sense of order. As it subverts centuries of human-centred beliefs and behaviours, the work of all these researchers is paving the way to a shift of perspective: a shift that feels particularly timely and needed, and that the whole design industry should embrace without hesitation.

Der Phytophiler von Dossofiorito, 2014

© Dossofiorito, Foto: Omar Nadalini

“Trying to understand plants is like learning a different language. This can only be achieved with care, closeness and observation.” This is the suggestion of Italian duo Dossofiorito (Gianluca Gia-bardo, Livia Rossi). Considering their houseplants as pets, in their work, the two designers emphasise the importance of establishing meaningful connections with them, and develop objects – see the projects The Phytophiler and Epiphytes, for reference – that try to spark curiosity and attentiveness towards plants in the domestic environment. The pieces become conversation starters between the houseplants and the humans that care for them, and also remind us that having plants at home is a responsibility that shouldn’t be taken lightly.

In her project Lingua Planta, the Dutch designer Merle Bergers invite us to understand the vegetal realm even more deeply. After studying the volatile organic compounds that plants use to alert others about dangers, attract pollinators or respond to pathogens, Bergers created a series of smellscapes based on this communication system. Called Defend, Attract and Repel, the three scents encourage us to have an embodied experience that connect us intimately with plants and their non-verbal ways of conversing among each other.

Lingua Planta von Merle Bergers, 2018

© Merle Bergers

Over the centuries, the fact that plants can communicate with other living beings – in ways that we can’t always easily grasp and comprehend – has excited the imagination of writers, artists, and scientists who dream of actually conversing with them. Attempting to do so, the designer Helene Steiner partnered up with Microsoft Research to develop Florence, a device that proposes to intercept the electro-chemical signals that plants emit, translating them in human language and thus enabling us to understand and respond to their needs. By merging the digital, human and vegetal worlds through the language of computation, the interface developed by Steiner tries to open up new possibilities of interaction with vegetal beings.

Helene Steiner, Florence, 2016

© Helene Steiner & Microsoft Research

3. Transformation

Parallel to these attempts, some other contemporary creatives are taking an even more radical stand on the idea of vegetal-based design and are developing projects that embrace plants as co-authors in the design process. What they suggest is to partner with living specimens to grow objects, embracing the pace of plants and favour cohabitation instead of domination.

Botanical Manufacture, 2017

© Carole Collet

Two prominent examples in this sense are the British company Full Grown – which is cultivating pieces of furniture in their garden-factory – and French designer and researcher Carole Collet who, since 2017, has been experimenting with the 17th century ancient Chinese craft of decorated gourd moulding. The vessels that compose Collet’s Botanical Manufacture series – which are co-designed with plants through moulds placed on the growing gourds – propose an alternative to rapid prototyping practices and spouse instead slow production methods, the beauty of imperfection, and failure as part of the design and realisation process. As Collet affirms, “when you shift the creative process from working with inert materials to designing with a living entity, the act of designing becomes radically different. Co-designing and co-working with plants requires a good understanding of the parameters of growth to sustain this ‘collaboration’. This requires a whole different toolkit for design and the adoption of new methods and protocols suitable for biofacture. Working with plants also demands a thorough understanding of botany, horticulture, permaculture and living systems principles. I believe these are the very skills designers need to embrace to be able to embed ecological values in their work fully.”

Botanical Manufacture von Carole Collet © CID Grand-Hornu, Foto: Tim van de Velde

In her project Botanical Bodies, designer Marie Declerfayt takes the idea a step further as she suggests the possibility of inserting bio-compatible wooden bones into our bodies, thus envisioning a new vegetalised posthumanism. While Declerfayt’s project might sound futuristic – or even extracted from a science fiction tale – it is interesting to note that actual scientific studies have shown that plants and humans have a similar vascular network structure that allows cross-kingdom tissues grafting. As Declerfayt powerfully expresses in her essay Blurring the Boundaries. Botanical Bodies, or Becoming a Plant-human Chimaera (Plant Fever Journal, January 23rd, 2021), “blurring species boundaries might help us go beyond our conception of the vegetal world as a passive, unconscious resource for human use and open us to a shared, embodied existence of cooperation, collaboration and consciousness.”

Botanical Bodies von Marie Declerfayt, 2019

© Marie Declerfayt

___

As researchers and curators, we believe that at a time of great anthropogenic pressure on the planet, design can (and should) act as a sensor and multiplier of novel ways of relating to and conversing with other-than-human worlds. Embedded in our capitalist society, design has, in fact, a role to play – and the responsibility! – in welcoming and supporting alternative narratives. It is its duty to sow seeds of inclusiveness instead of domination and to seek novel approaches instead of relying on old schemes that have already been proven wrong.

The touring exhibition Plant Fever (Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden, until October 31st, 2023) and this summer’s School of Phyto-centred Design at the Design Campus hope to be some of the platforms where such conversations – but also actions! – can take place. As witnesses of their time, the creatives featured in these two endeavours are looking at the plant world with renewed curiosity. The panoramic field of vision offered by their transdisciplinary journeys calls into question not only the ambient hyper-specialisation but also the boundaries drawn between living beings – humans and non-humans.

The paths and conclusions of their wanderings are varied, but all of them should be taken into account as serious suggestions for questioning the status quo. One might argue that most of these initiatives remain profoundly human-centred (one of the main goals being the postponement of the collapse of the world as we know it). Nevertheless, these endeavours have the merit of opening the way to a more vegetal and collaborative approach to design that shall benefit all beings instead of leaving some behind. By helping to “stage liveable futures for both plants and people” – to use the words of Canadian professor Natasha Myers – they can be a way to thwart centuries of extractive and subjugating practices. And to think and become more plant-like.

Also of interest:

Inspired by ongoing initiatives and projects of contemporary international designers, engineers, artists and writers, the following phyto-based actions are not addressed solely to practitioners, but call for everyone's (including producers’ and consumers’) sense of respect, responsibility, equity and empathy towards plants. They should be read not as rules but as invitations to see the world through the perspective of plants.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/e/csm_Plant_Fever_The_Manifesto_of_Phyto-centred_Design_Photo__c__Olly_Cruise__studio_d-o-t-s_-_Horizontal_cut_High_Res_96813b1039.jpg)

The Design Campus summer program is a “School of Utopias”. It is a visionary design school set to explore complex problems, dream bold ideas, and collaboratively build new ways forward. This year was curated by the design duo Formafantasma and was all about a foray into the world of the museum, its environs and networks. Formafantasma on the programm of this year's Summer School:

From 1840 to 1841, the city of Dresden escaped an outbreak of cholera, probably thanks to measures that had been taken. Shortly after, on 5 November 1841, Captain Eugen Freiherr von Gutschmid, a baron, art patron and honorary member of the Royal Saxon Academy of the Arts, commissioned the architect Gottfried Semper to design and build a monument to the event in “Gothic style”; the architectural style to which Gutschmid himself was most attached.