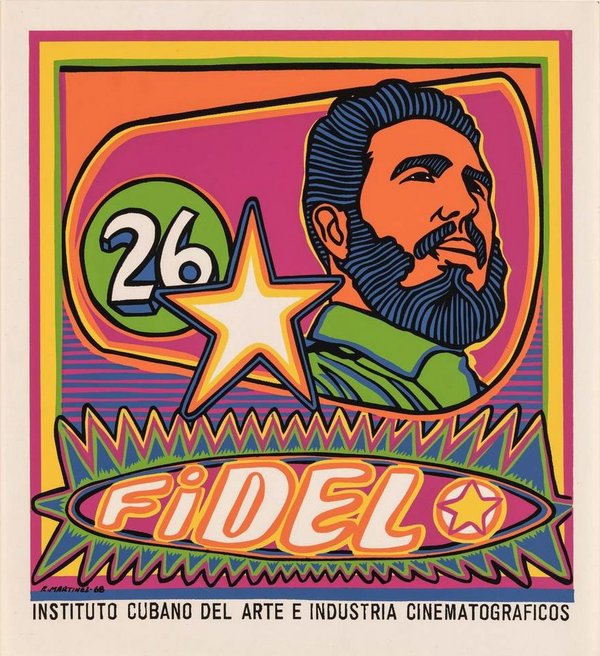

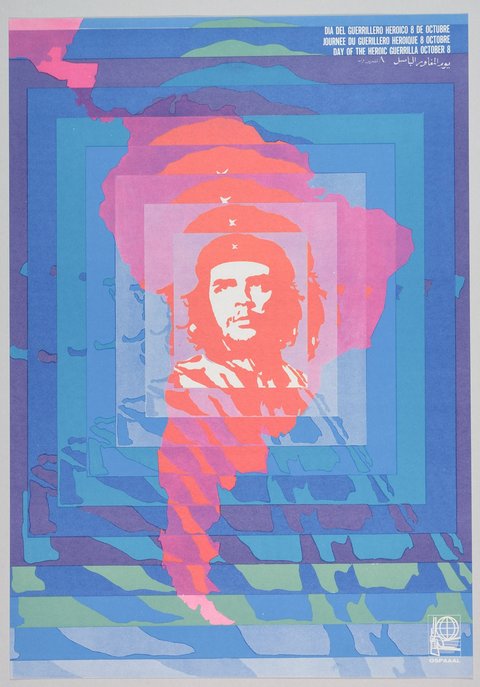

Elena Serrano: Dia Del Guerrillero Heroico 8 de Octubre (8. Oktober, Tag der heldenhaften Guerilla), 1968

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The fate of Cuban culture depends on the fate of the revolution. Therefore: Defending the revolution is equivalent to defending culture.

Gert Caden [Einführung], in: Grafik aus dem neuen Cuba, Ausst.-Broschüre Museum für Deutsche Geschichte, Berlin-Ost 1961, Berlin 1961, o. S. – Zum Zitat des Aufsatztitels: deutsche Übersetzung »Wir sind der Welt ein Beispiel«, Titel des Plakats eines unbekannten kubanischen Künstlers im Dresdener Kupferstich-Kabinett, Inv.-Nr. A 1963-25.

1 Vgl. Marcus Kenzler, Der Blick in die Welt. Einflüsse Lateinamerikas auf die Bildende Kunst der DDR, Berlin 2012, S. 116–118.

The small collection of just under 70 Cuban artworks in Dresden’s Kupferstich-Kabinett exemplifies the impact of cultural policy on the collecting activities of GDR museums. They came to be part of the collection in three different ways during the 1960s. Inspired by the preparations for the Revolutionary Romances exhibition in the Albertinum, for which planning began in autumn 2020, and which examines artistic ties between the GDR and the countries of the Global South, more light is now being shed on this collection. The fact that it received little attention is also apparent from a conservational perspective: Until now, most of these works had been stored loose in folders or rolled up as bundles under the heading ‘Not displayed’.

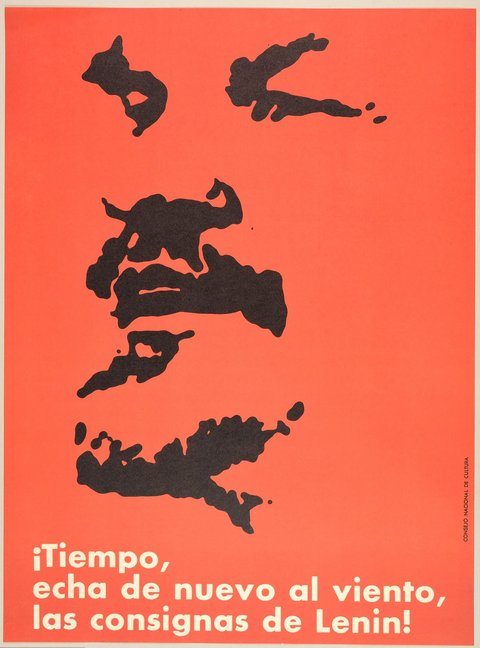

Unbekannt: iTiempo, echa de nueva al viento las consgnas de Lenin!, nicht datiert (1960/70)

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

The acquisition documents reveal that the first two batches were probably received for diplomatic rather than art history considerations. Lea Grundig (1906–1977), at the time Professor of Graphic Art at the University of Fine Arts in Dresden, likely brought numerous graphic prints back to Dresden from a trip to Cuba and donated them to the Kupferstich-Kabinett.2 Most of the works deal with the revolution. In 1962, she wrote the following Werner Schmidt (1930–2010), the then Director of the Kupferstich-Kabinett:

Please find attached the list of the Cuban graphic prints I am donating to you. It is with great pleasure that I do so and hope they will help to strengthen our cordial ties to revolutionary Cuba and the friendship between our nations through art.3

The list comprises 65 works by 27 artists. However, Werner Schmidt only chose ten works and replied to Lea Grundig as follows:

You must understand that we can only accept what we consider, to the best of our knowledge, the most artistically important works into our collection, to give an impression of Cuban graphic art at its best.4

2 The chronological correlation between Lea Grundig's journey and the donation to the Kupferstich-Kabinett suggests that she brought these prints back from Cuba.

3 Lea Grundig to Werner Schmidt, 26.9.1962, Archiv der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD), 02/KK 63, Bd. 1, o. Bl.

4 Werner Schmidt to Lea Grundig, 6. 2. 1963, ebd.

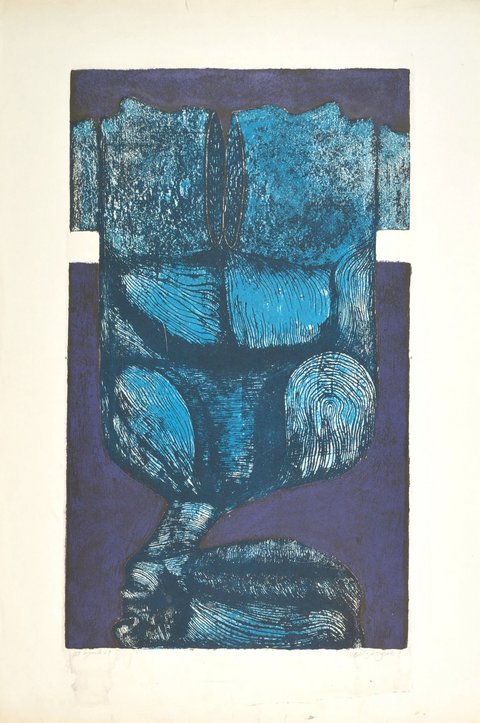

Alberto Ortiz de Zárate: Frau, stürzend, 1962

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

5 SKD, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Inv.-Nr. A 1963-21.

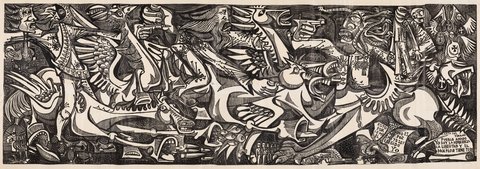

The second woodcut, by Umberto Peña Carriga (*1937), is thematically and formally influenced by the art of Pablo Picasso in the 1930s, and in particular Picasso’s 1937 large-format painting Guernica. The work entitled Las Dictaduras en America is an allegorical depiction of the rebels’ struggle against dictator General Batista.

Umberto Peña Garriga: Las dictaduras en America, nicht datiert

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

6 Vgl. Gerhard Pommeranz-Liedtke, Die Revolutionäre »Asociación

de Grabaderos de Cuba«, in: Kubanische revolutionäre Graphik, Dresden 1962, S. 5–28,

hier S. 12.

7 It can be assumed that this donation was also arranged by Lea Grundig, who had been chairwoman of the VBK since 1964.

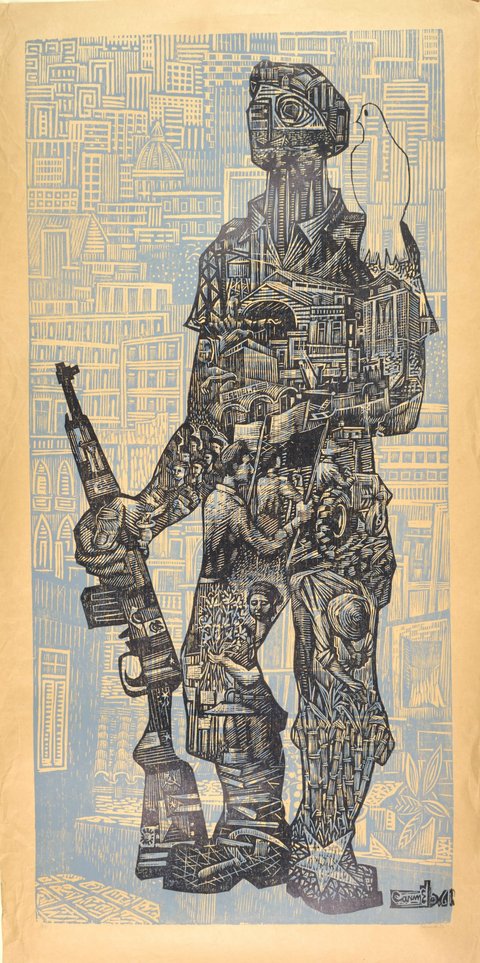

Carmelo Gonzáles: Auf Wache, 1961

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

I do not think it is right that all 30 woodcuts should be part of our collection as the works would only be rolled up in our depot and it would be almost impossible to give even to visitors to the study room access to them as there are no cardboard backings large enough for these woodcuts.8

8 Werner Schmidt to the General Directorate, 28.10.1965, Archiv der SKD, 02/KK 68, S. 103.

9 Werner Schmidt to the General Directorate, 9.11.1965, ebd., S. 106.

10 From July to September 1975, the Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister organised a solo exhibition of paintings, drawings and prints of Carmelo González Iglesias.

11 Christian Dittrich, travelogue, 6.11.1969, Archiv der SKD, 02/KK 204, o. Bl.

12 Christian Dittrich, travel application, 28.5.1969, ebd.

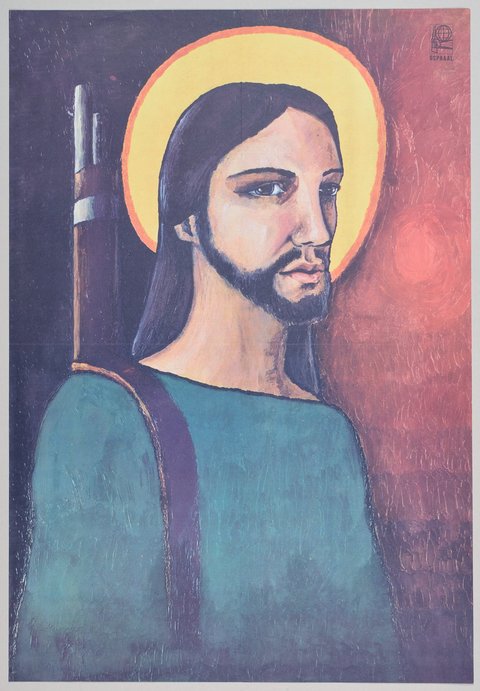

Alfredo González Rostgaard: Ohne Titel (Cristo Guerrillero), 1969

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

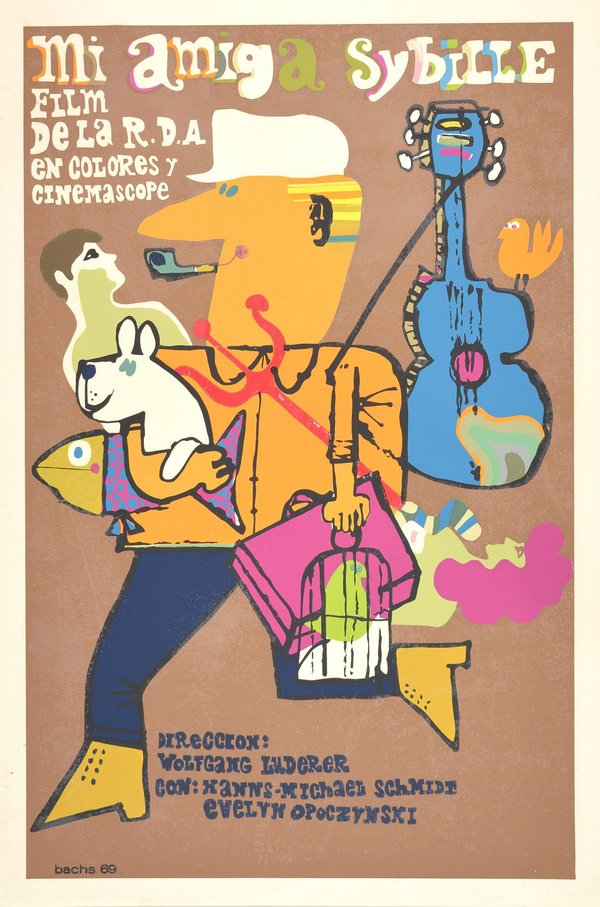

During his visit from 9 August to 14 September 1969, Dittrich assessed in particular the museum’s graphic collection, specified attributions and dates of European works and advised on the system for arrangement and storage of the collections. He also visited many other museums as well as institutions and graphic design workshops and gained an overview of contemporary Cuban art by touring galleries and studios. With the support of the National Cultural Council of Cuba, Dittrich was able to purchase some graphic prints, and received others as gifts from the artists. After his return, these 21 graphic prints were added to the collection of the Kupferstich-Kabinett.

Dittrich’s selection differs from the previous donations, being more varied in form and content. The works include both abstract art and bold colours as well as figurative and realistic lithographs and woodcuts in black and white. This collection is entirely devoid of revolutionary motifs.

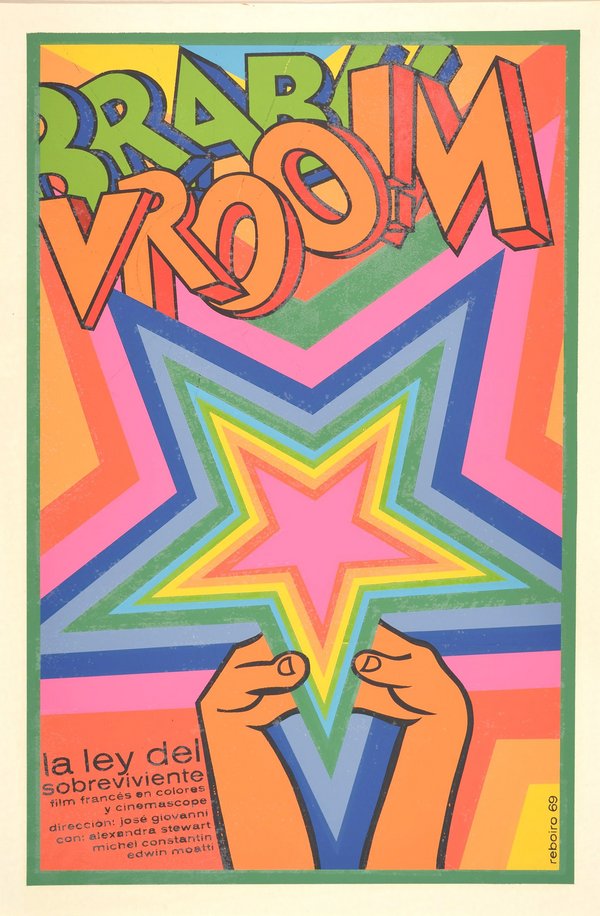

He also brought many silkscreen-printed film posters back to Dresden. It is astonishing that they were not added to the inventory at the time, as Dittrich highlighted their formal quality, which was inspired by pop-art:

Pedro Pablo Oliva: Explosion, 1969

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Andreas Diesend

Dittrich’s acquisitions were the last additions of Cuban art to the Kupferstich-Kabinett collection, with the exception of three individual works which were later added to the inventory.14 The last work received – the only drawing in the collection – was a gift to Erich Honecker on his state visit to Cuba in 1980. The 1976 work by René Portocarrero (1912–1985) shows the head of a young woman in profile, overgrown by a sea of colourful flowers. It bears no resemblance to the new political dawning evident in the graphic art of the 1960s.

13 Vgl. Christian Dittrich, Kubanische

Kunstnotizen. Im Museo Nacional, in der Experimentierwerkstatt für Graphik und in Künstlerateliers von Havanna zu Besuch, in: Dresdener Kunstblätter 15 (1971), Nr. 4, S. 122–125, Nr. 6, S. 170–177, hier S. 173.The film posters were inventoried in the course of the research for this article in May 2020.

14 SKD, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Inv.-Nrn. C 1981-231 (Zeichnung von René Portocarrero), A 1983-53 und A 1983-54 (Lithografien von Rafael Zarza).

In the context of decolonial investigations focusing on the art of the Global South, collections like that presented here become increasingly relevant, perhaps for the first time. As an ambassador for cultural policy, art was collected in the GDR for political motivations, rather than choosing based on quality criteria as would have been the case had those involved had the freedom of choice. Today, however, the Cuban collections in the Kupferstich-Kabinett are an exemplary demonstration of the influence of contemporary events on collection activities: the influence of political frameworks and personal relationships, of government-commissioned art and highly personal ‘revolutionary romances’.

* The author would like to thank Consuelo Dittrich for the interviews and important information.

This text was first published in issue 3/2020 of Dresdener Kunstblätter.

Also of interest:

The annihilation of Vinh City by US bomb raids offered an opportunity for experimental planning and for transforming the small industrial town into a model socialist city. The GDR’s ambitious task of comprehensive reconstruction involved working collectively on both the creation of a master plan and its realization in built form. Christina Schwenkel on the Quang Trung housing complex.

Pamela Meyer-Arndt's film "Rebellinnen" is dedicated to the artistic urge for freedom of three female artists in the GDR in the 1970s and 80s. The director, two of the artists - Tina Bara and Gabriele Stötzer - and Dr Angelika Richter came together at the Albertinum for a discussion in which they talked about the making of the film as well as the living conditions and artistic hardships of those years.

From 1840 to 1841, the city of Dresden escaped an outbreak of cholera, probably thanks to measures that had been taken. Shortly after, on 5 November 1841, Captain Eugen Freiherr von Gutschmid, a baron, art patron and honorary member of the Royal Saxon Academy of the Arts, commissioned the architect Gottfried Semper to design and build a monument to the event in “Gothic style”; the architectural style to which Gutschmid himself was most attached.